I made a great discovery during the summer of 2015. While driving through the Mississippi Delta, a sign welcomed me to Greenwood, “Home of 5-Time Olympian, Willye B. White.” Who? I did a Google search. Willye B. White was a Black girl born with fast feet like Hermes. Running from work in cotton fields, she raced in international track competitions from 1956 to 1972.

I was teaching school. There was no time to research Willye’s life. But in 2020, the pandemic shuttered school, and in the quietness, I remembered Willye White and that welcome sign. The pandemic made space for me to document the achievements of this U.S. Olympian — Black, female, poor, and significant to Tennessee history. My research began on the phone. Former Olympic swimmer Donna de Varona encouraged me to contact Pat Connolly. Connolly and White called themselves “soul sisters.” Connolly is a retired pentathlete and coach who trained U.S. Olympians Evelyn Ashford and Allyson Felix. She put me in contact with former Olympian and Tennessee State University (TSU) track star, Ralph Boston. My uncle, Hugh Strong, connected me with former Olympian, TSU Tigerbelle, and Memphis educator Margaret Wilburn.

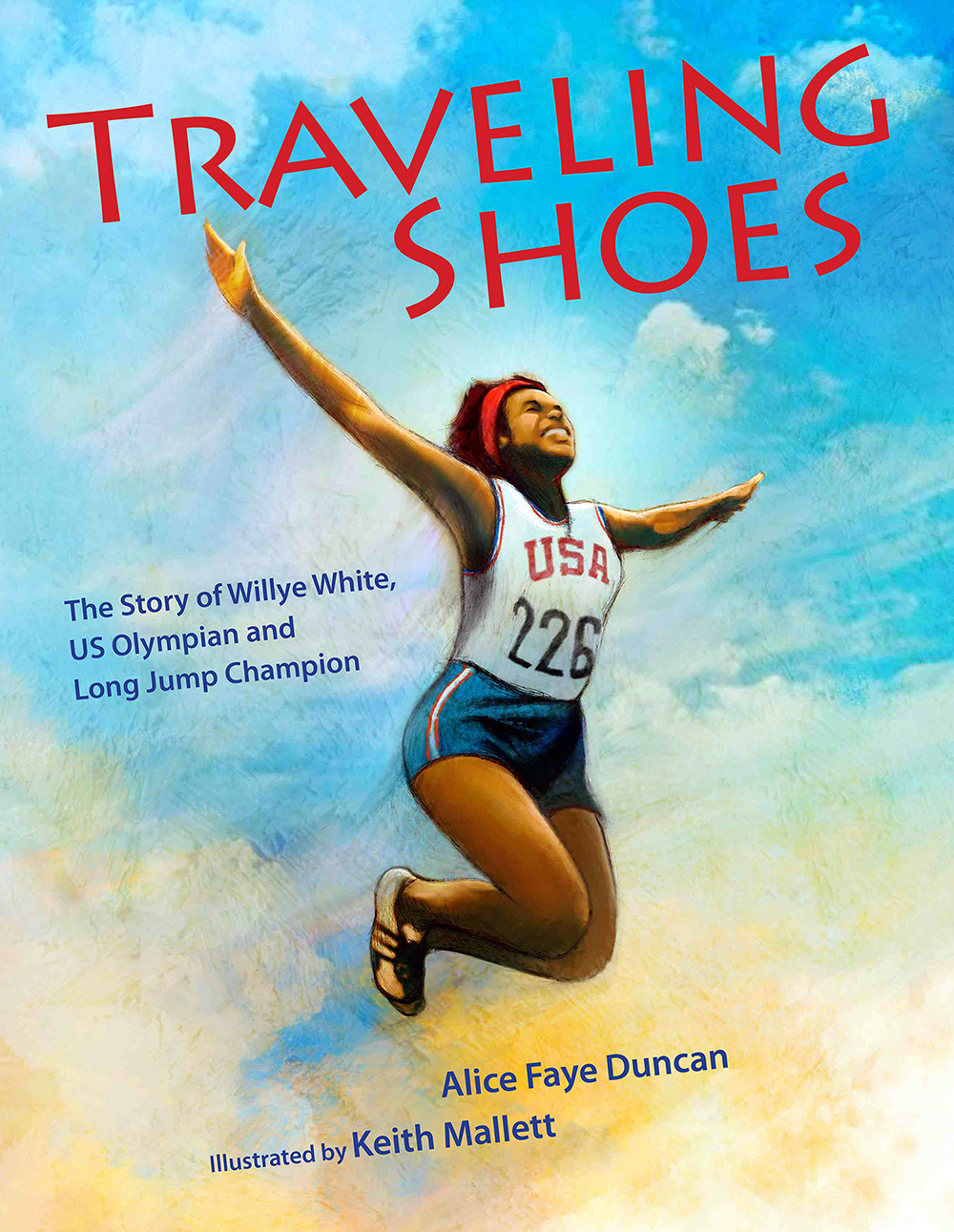

Boston and Wilburn ran with White at TSU. They remembered her to be a resilient athlete and charismatic talker who was called “Mississippi Red” because of her ginger hair. Interviews served me a three-dimensional view of Willye. She was a runner, world traveler, and wise woman, quick with sage observations. For instance, when it came to brutal challenges on the track and in the crucible of the Jim Crow South, she said, “People are always trying to take away my smile, but it’s mine, and they can’t have it.”

After speaking with Willye’s friends, I wrote the first biography about one of the greatest U.S. Olympians to go uncelebrated in the history books. With palpable excitement, as we approach the 2024 Summer Olympics, the amplification of Willye’s valor begins with me.

Willye White was the first American to compete for 20 consecutive years during five Olympic Games in track and field. She sprinted and jumped as a member of 39 U.S. international teams, including the first team to visit the Soviet Union in 1958 and first team to visit China in 1975. She set seven world records. And for nearly two decades, Willye was the best female long jumper in the nation with a career high of 21 feet, 6 inches. White’s maternal grandparents, Louis and Edna Brown, were unskilled laborers who raised her up in Greenwood. They inspired her love for learning. Despite Willye’s reading challenges, she graduated high school in 1959. She graduated Chicago State University in 1976. When she was in fifth grade, her older cousin Vee invited Willye to try out for her high school track team. Willye made the team and sports fueled her self-confidence. She said, “Athletics were my freedom. Freedom from ignorance, freedom from segregation.”

Olympians trained without corporate sponsorship in Willye’s day. So she supported herself working full-time in a Chicago hospital, while training before and after work. Her passion for track was a free ticket to see the world. At 16 years old, in 1956, she participated in her first Olympic Games and won a silver medal in the women’s long jump. She was the first American woman to medal in this event. Willye lived in Greenwood but trained during the summers in Nashville, Tennessee, with Ed Temple, the women’s track coach at TSU. Training in Nashville was her escape from picking cotton. And upon high school graduation in 1959, Willye joined Ed Temple’s TSU Tigerbelles as a freshman. Olympic gold medalist Wilma Rudolph was her Tigerbelle teammate and friend.

It was Coach Temple who nicknamed Willye White “Mississippi Red.” When Red started socializing off campus and missing curfew, Temple canceled her scholarship. She withdrew from TSU in 1960 and moved to Chicago. Temple met Willye again in the summer of 1960 and 1964 when he coached the U.S. Women’s Olympic track teams in Rome and Tokyo. The two mended their differences, and during the 1964 Games, he added her to the 4×100-meter relay race. With Wyomia Tyus, Edith McGuire, and Marilyn White, she won her second silver medal for the USA.

Willye established her track career during the turbulent years of the Civil Rights Movement. While Dr. King marched in street protests, Willye contributed to Black progress on the track with muscle and might. At the end of her track career in 1972, she served as a Chicago city administrator. She also coached student athletes. Willye’s winning mantra was, “If it is to be, it is up to me, because I believe in me!”

Mississippi Red died in 2007 from pancreatic cancer. The city of Chicago named an athletic complex in her honor. You can visit the Willye B. White Park at 1610 W. Howard Street, Chicago, Illinois.

Alice Faye Duncan is the official biographer for U.S. Olympian and TSU Tigerbelle, Willye B. White. Traveling Shoes is the story of Willye’s grace and grit. You can find more books from the author at alicefayeduncan.com.