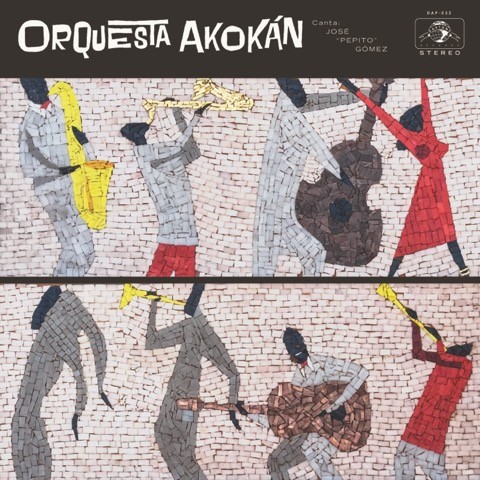

Orquesta Akokán

Old Glory isn’t the only red, white and blue we can celebrate this weekend. That other revolution, nearly 200 years after the United States’, may have shaken up the traditional stew of influences that always made Cuba a musical dynamo, but the island’s deep lineage is as powerful as ever today. Orquesta Akokán, appearing at the Levitt Shell on Saturday, July 6, is proof positive. Touting a Grammy Award nomination for “Best Tropical Latin Album,” and making the “Best Of” lists of numerous media outlets, the big mambo sound of the band is catching on fast. And it was all spurred on by a record cut live to tape over a three-day session at Havana’s hallowed state-run Estudios Areito, one of the longest operating studios in the world.

The album was produced by Jacob Plasse and arranged by Mike Eckroth, and I recently had a chance to ask Plasse about the album’s genesis and how it spawned the current juggernaut touring band.

Memphis Flyer: Cuban music is fascinating because it’s hard to wrap my head around the syncopation and the timekeeping, as a musician. I enjoy the way it mystifies me.

Jacob Plasse: I can definitely relate to that. Because I’m not Cuban, and I learned Cuban music coming from jazz. So it took me a long time and a lot of embarrassing gigs of getting lost, rhythmically, before I felt comfortable. And still, I feel like I can always get better. Some of the things you do are so simple, but to get them right, really in the pocket — it’s very apparent in Cuban music the degree that you are or are not in the pocket. If you look at rock bands, like the Rolling Stones, things can be a little loose, and that’s cool. That’ s part of the style.

That is not the case with Cuban music. There is no “one”. Like the fourth beat is really one. In rock music you have a bass drum hitting on the one. In Cuban music, everything hits on the four. Mambo music less so than other types of Cuban music, which kind of makes it easier, but still even that too. The congas hit on the four, the bass hits on four, usually the piano or the guitar is accenting four.

With historically rich recordings and projects like the Buena Vista Social Club, it seems the Cuban musical scene has a keen appreciation of its past, that there’s a great continuity with music of the 40s or earlier.

Not exactly. I’m not really a historian, but I think the most important event in Cuban music is the Cuban Revolution. Before that there was so much interaction between New York and Havana, and after that things split in two. You can hear things sort of change. Then a big part of mambo music actually happened in Mexico, and had to do with the Mexican film industry. Perez Prado came out of that. Basically, after the revolution the American recording music isn’t as important; it can’t go to Cuba and record.

So then the Cuban thing becomes nationalized, and what the Cuban government, Fidel and the Communist Party, wanna promote is not music like mambo, which is coming out of the casinos. That became frowned upon, so it sort of disappeared in a way. Other styles become more prominent. This big band sound that is so American falls heavily out of favor in that period.

Yet the old traditions were preserved enough for things like the Buena Vista Social Club to come together.

Well, I think in time the government gradually let all that come back. Because it was a money and cultural cash cow. And Buena Vista helped a lot of people become familiar with Cuban music. I think our music is pretty different than Buena Vista. It’s very much related, it’s still Cuban music, but with the instrumentation, the sounds, it’s definitely a different thing.

Yet without the Buena Vista, I wonder how much interest people would have in my group. And that was how I was exposed to a lot of Cuban music too. It was a great starting point. And I fell in love with it and learned about all these other things. I think the Buena Vista is wonderful for what it’s done for people’s understanding of the music.

How do you understand Cuban music’s cultural importance? What do we get from Cuban music?

What I love about Cuban music is its unification of what people can dance to and what’s art music. It’s all very advanced, harmonically and rhythmically, and yet people can dance to it. The way into all this is through dance. And if you listen to some mambo stuff, like Perez Prado and stuff, there’s often a lot of dissonant harmonies. Those Perez Prado recordings from the 60s are weird! It’s like nothing else. And full of pretty advanced ideas that you find more in film music or something. But because it’s couched in these African dance rhythms, people can understand it and it’s a gateway in.

How did Orquesta Akokán come to be?

Me and Mike Eckroth and singer José “Pepito” Gómez all lived in the New York area. And I had a musical, and Mike and Pepito had played sometimes in my band, Los Rancheros. So we knew each other from the New York scene. And then we started writing these songs. Mike especially is incredibly knowledgeable about this style and this time. He has a doctorate in Cuban music, if you can believe it. So we wrote these songs and tried recording them in New York. It was okay, but it wasn’t anything earth shattering.

And then Pepito, the lead singer, was going down to Cuba. He’s actually kind of a famous timba singer, which is a modern style of Cuban music. He said, ‘Why don’t you come down? And why not bring the arrangements, maybe we can work on the tunes.’ And then he said, ‘Let’s book a studio!’

Then all of a sudden we were recording an album with all these legends of Cuban music that Pepito and Cesar had assembled. So Orquesta Akokán was sort of a recording project, and making records is what I do for a living, but this one, for some reason, everyone loved. Dap-Tone ended up releasing it, then they really wanted us to tour. So we became a touring band. And now it’s this whole business or something. It’s really incredible. The band sounds great and people are really receptive, which is wonderful.

How did the recording sessions in Cuba take shape?

Me and Mike and Pepito just wanted to make a cool album. It’s not easy to get everything through production in Cuba, because there are these variables. But Cesar Lopez, our saxophone player, arranged it all. Recording it, we had this wonderful studio the size of a gymnasium in central Havana. Nat King Cole recorded there. All the legends. So you walk in there and you feel special. Like no recording studio I’ve every been at that. That room is really special. And that’s really all you need.

What kind of scene and sound should people expect when they show up at the shell Saturday?

People should expect to dance. There’s nothing like a really killing rhythm section live. The record comes alive in so many ways when we play it. It has a new energy to it. Those rhythms are meant to be felt and heard in person. There’s a connection that happens that doesn’t happen otherwise.

The Other Red, White & Blue: Orquesta Akokán Brings Cuba’s Finest