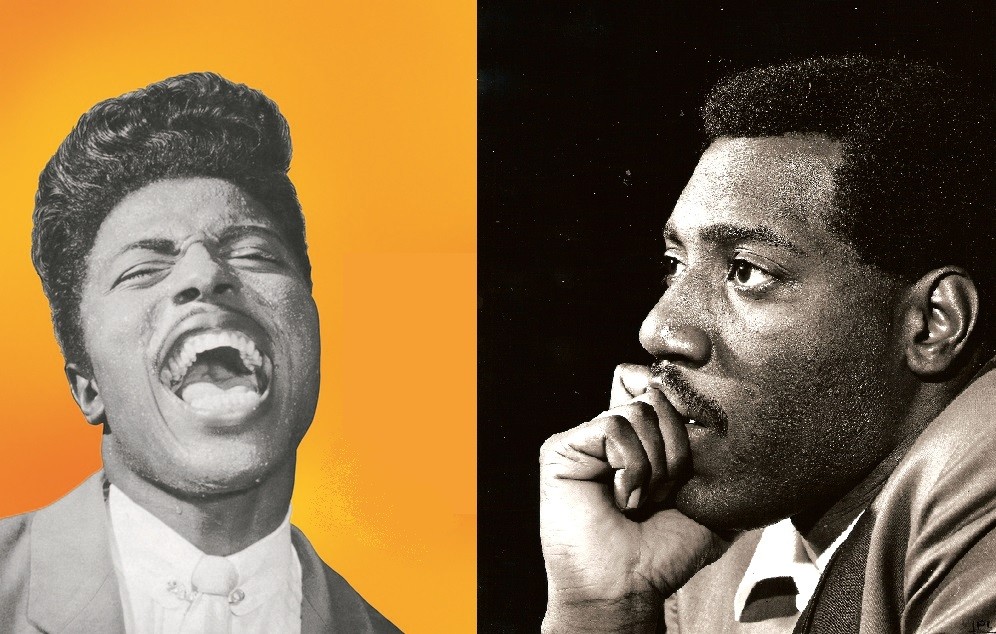

From blues to rock-and-roll to soul, rap, and funk, Memphis has played a seminal role in producing some of the world’s most talented and groundbreaking music artists: B.B. King, Elvis Presley, Al Green, Isaac Hayes, Otis Redding, Sam Moore and Dave Prater, Rufus Thomas, Booker T. & the MGs, Bobby Blue Bland — the list goes on and on.

Though you may not often hear the Bar-Kays mentioned in that illustrious roster, they should be. The group has been musically linked to many of those artists — especially Redding — and is still rocking after nearly five decades in existence. Formed in 1966, the original group consisted of bassist James Alexander, guitarist Jimmie King, saxophonist Phalon Jones, drummer Carl Cunningham, trumpeter Ben Cauley, and organist Ronnie Caldwell (its only Caucasian member). Several decades later, boasting only one of the group’s founding members — Alexander — the Bar-Kays’ legacy continues.

Not too many groups have achieved the decades of accolades the Bar-Kays have — a platinum album, six gold albums, and more than 20 Billboard Top 10 singles.

Now, more than 45 years after the release of their 1967 debut single, “Soul Finger,” the Bar-Kays are prepping the release of their latest, yet to be titled album. The group’s latest single, “Grown Folks,” a mature R&B groove, has made its way onto Billboard’s Top 10 Adult R&B chart. And the group continues to tour and entertain thousands of fans around the globe.

“The group’s mission has always been, when all else fails, make some feel-good music,” Alexander says. “We still have something to say.”

“It’s so rewarding to know that having made 30 albums, people still appreciate [the music],” says lead vocalist Larry Dodson. “We’re having the time of our life.”

> The Early Years

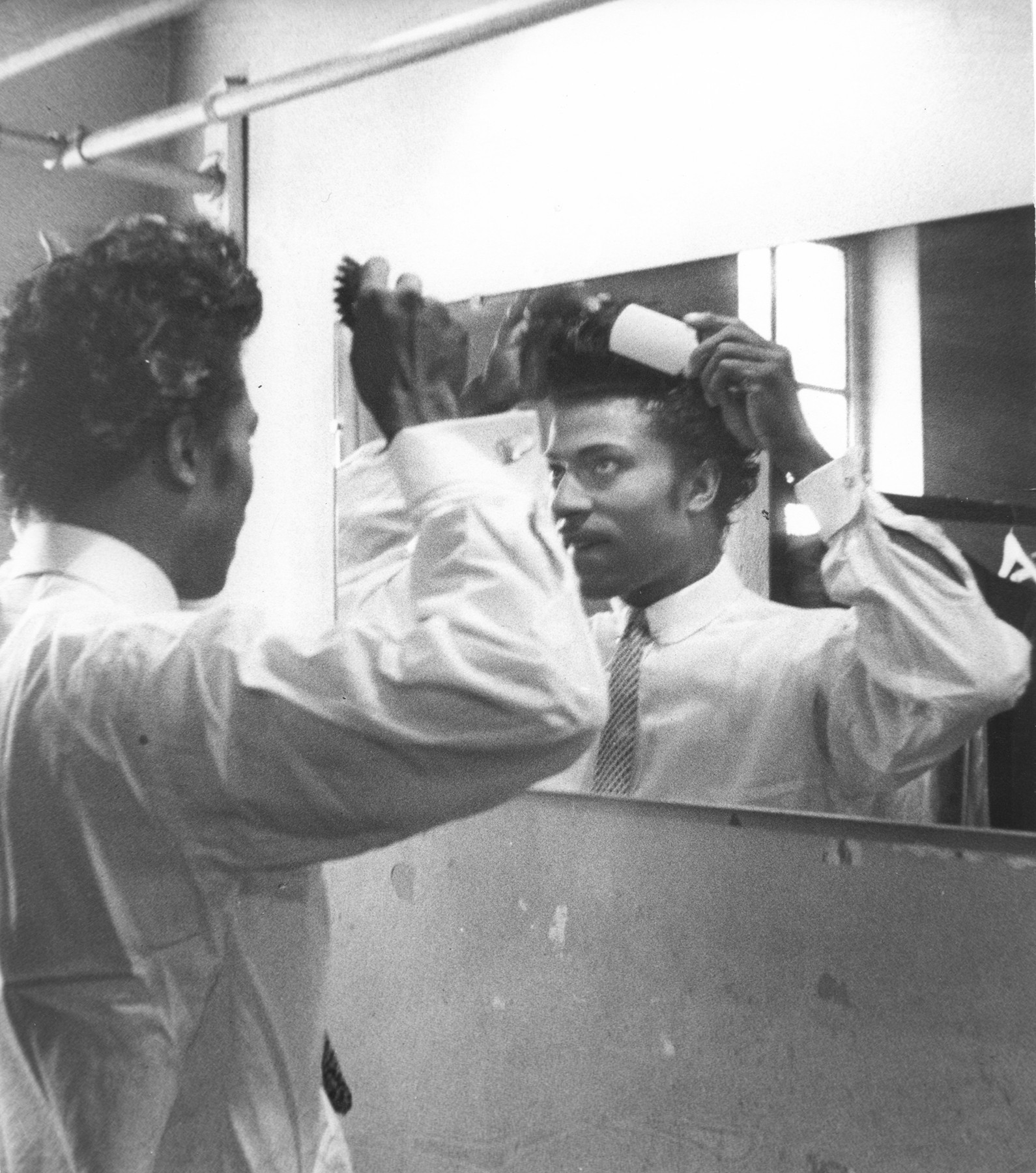

The Bar-Kays’ founding members played together in the Booker T. Washington High School band. Originally an instrumental collective known as the Rivieras (not to be confused with the ’60s rock-and-roll group), they decided to change their name to the Bar-Kays after noticing a billboard advertisement for Barclay Rum on the way to a performance. They adopted a mutated version of the name.

The sextet eventually caught the attention of Stax Records and was chosen to be the back-up band for many of the label’s artists, including the Staple Singers, Rufus Thomas, and Otis Redding.

The Bar-Kays’ first single, “Soul Finger,” was released on Stax/Volt Records in 1967. The track begins with a brief instrumental riff of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and is followed by soulful, funky doses of bass, trumpet, and drums. In the background, kids can be heard chanting, “Soul finger!”

“I got kids off the street and directed them like a choir to scream and holler and shout,” says legendary songwriter and producer David Porter. “I thought quite highly of the group, so when they [made] the track, I got Isaac [Hayes] and we just helped them by coming up with the song’s title, the chants, and all that on the record. It became [one of the] biggest records they’ve ever had.”

The song reached number 17 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and number 3 on the R&B chart. The same year, the group released its debut album, also titled Soul Finger, and began to gain national notoriety. (Decades later, “Soul Finger” was featured in the 2007 comedy Superbad, as well as the 2009 musical comedy Soul Men.)

Stax labelmate and soul legend Otis Redding took a liking to the Bar-Kays and selected them to be the back-up band for his national tour. The group began to travel with Redding to performances on his private plane, a twin-engine Beechcraft 18.

“Playing with Otis Redding was very special,” Alexander says.

“We had a lot of fun. It really taught us about having a real competitive spirit. Every time he went out to perform, he always strived to be the best he could be and that filtered down to us.”

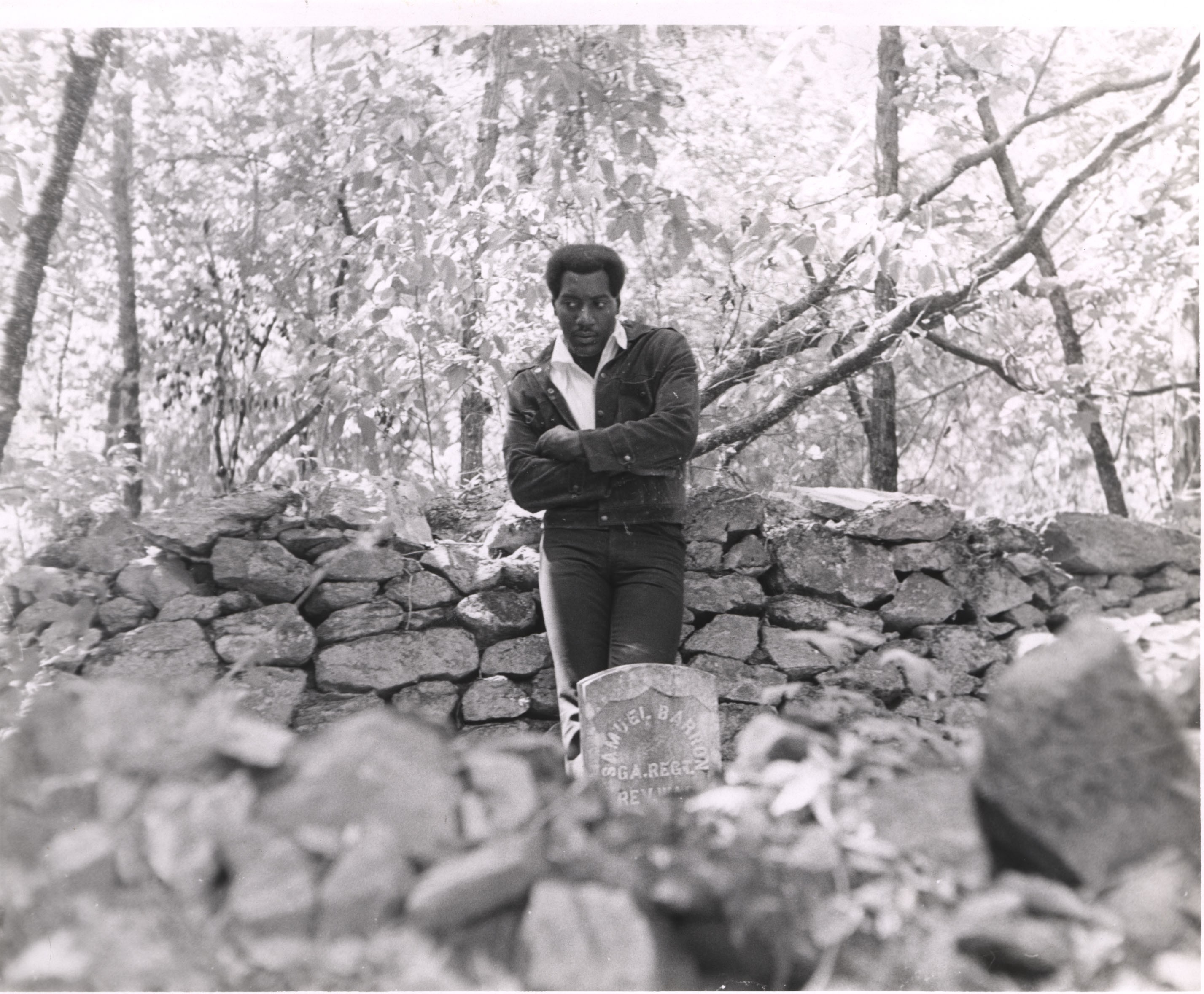

> Tragedy Strikes

On December 9, 1967, Redding and the Bar-Kays flew to Cleveland, Ohio, to make an appearance on Don Webster’s Upbeat TV show. The following day, they had a scheduled performance in Madison, Wisconsin.

On the stormy afternoon of December 10th, Redding’s pilot took off for Madison. Passengers included Redding, his manager, and Bar-Kays band members King, Caldwell, Jones, Cauley, and Cunningham.

The plane began to shake, as the poor weather conditions intensified. Around 3:30 p.m., the plane plunged into the Squaw Bay area of Lake Monona, a couple miles shy of Madison’s Truax Field. Cauley was the only survivor. He escaped death by clinging to a seat cushion, while watching his friends cry for help before disappearing into the lake’s frigid water.

“I saw all of them drown,” Cauley recollects. “It affected me in a big way. I sat around and thought about it. I cried and cried.”

Alexander had taken a commercial flight, because Redding’s plane only had eight seats. His life was spared, but he had the horrific task of identifying the bodies of Redding and his band members.

“When I got the news, it had a profound effect on me,” Alexander says. “All my friends, we played together, so I was devastated. The thing that kept me going was [that] we always had a habit of saying if something happened to one of us, we would carry on. So that’s what we did, we kept it going.”

> The Reemergence

In 1968, Cauley and Alexander reassembled the band with a new lineup that included guitarist Michael Toles, keyboardist Ronnie Gordon, saxophonist Harvey Henderson, and drummers Roy Cunningham and Willie Hall.

Like the original Bar-Kays, the revived group became a house band for Stax/Volt recording sessions and played on such albums as Isaac Hayes’ Hot Buttered Soul, Black Moses, and his Grammy Award-winning soundtrack, Shaft.

In 1969, the Bar-Kays released their second album, Gotta Groove. It didn’t receive the same response as their debut, but things would improve for the Bar-Kays when they acquired Dodson as their first and, to date, only lead vocalist. Prior to joining the Bar-Kays, Dodson was a part of the soul group the Temprees.

“After being an instrumental group for so many years, their producer, Allen Jones, and the band decided to get a frontman and make a transition to a singing group,” Dodson explains. “They had their eyes on me. It was something they saw in me that I certainly didn’t see in myself.”

Dodson’s high-pitched but passionate and charismatic voice would prove to be a perfect fit for the group’s funky instrumentation. The Bar-Kays released Black Rock with Dodson doing vocals in 1971. The album broke musical barriers with its fusion of soul, rock, and funk.

The Bar-Kays put their own melodic twist to hit songs such as Porter and Hayes’ “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” Aretha Franklin’s “Baby, I Love You,” and Curtis Mayfield’s “I’ve Been Trying.” Although Black Rock didn’t boast any chart-topping singles, it remains one of Alexander’s and Dodson’s favorite Bar-Kays albums.

“How many black guys who were raised up on soul were doing a mixture of soul, funk, and rock music?” Dodson says. “Doing songs that were not only from a R&B base but mixed in with rock influences, metal guitar, and long arrangements? Black Rock was so much ahead of its time.”

The group released two more albums on Stax Records, Do You See What I See? and Coldblooded and also starred in the Golden Globe-nominated documentary Wattstax before the label’s bankruptcy in 1975. The label’s song catalog and name were purchased by California-based Fantasy Records in 1977.

“Stax was like an institution to us,” Alexander says. “It was like going to college. We got all this on-the-job training by being around people like Jim Stewart, Al Bell, Estelle Axton, Isaac Hayes, David Porter, Booker T. & the MGs, and our long-time manager and producer, Allen Jones. These people took us under their wing and helped mold and shape us.”

> Hardship and Success

Stax’s bankruptcy left the group without a label. To make ends meet, they began performing at the Family Affair nightclub in Memphis. During the year the group played at the club, they penned such hits as “Shake Your Rump to the Funk,” “Too Hot To Stop,” and “Spellbound,” which would ultimately earn them a deal with Mercury Records.

In 1976, they released their Mercury label debut, Too Hot to Stop, which featured the hit song “Shake Your Rump to the Funk” (also featured in the comedy Superbad), along with other funky tracks and soulful ballads.

The group followed up with 1977’s Flying High on Your Love, which reached number 7 on Billboard’s R&B chart and earned the Bar-Kays their first gold record.

Seeing their success, Fantasy Records brought out some of the Bar-Kays’ unreleased material that was recorded prior to Stax’s bankruptcy. That album, Money Talks, came out in 1978 and featured the Top 10 single “Holy Ghost.”

“I just thought that was such an epic record,” says James Alexander’s son, Jazze Pha, the Atlanta-based, multiplatinum producer. He appreciates the contributions made by his father’s group. “When I think of the Bar-Kays, I think of great lineage. I think of the great foundation that they built for young folks as a reference to go back and see what real music sounds like.”

The Bar-Kays kept the momentum going with 1979’s Injoy, which featured the Billboard-charting dance hit “Move Your Boogie Body.” The album featured the group’s funky experimentation with the then-dominant disco genre. Injoy went gold and reached number 2 on Billboard’s R&B album chart.

While churning out the hits on record, the Bar-Kays also became known for their over-the-top live performances. They wore outlandish outfits — headbands, fur boots, flashy colors — and entertained audiences with fire, smoke, funky dance routines, not to mention the boa constrictors and pythons that Dodson would sometimes bring out in the shows’ final minutes.

“The Bar-Kays were an incredible show band,” says Johnnie Walker, executive director of the Memphis & Shelby County Music Commission. “The costumes, the dancing, and, obviously, the music was the primary ingredient. You knew if you bought that ticket, you were getting your money’s worth.”

During the 1980s, the group released several more albums on Mercury, including Nightcruising in 1981 and Propositions in 1982, which featured the classic ballad “Anticipation.” Both went gold.

Their 1984 album Dangerous featured the party hit “Freakshow on the Dance Floor.” The song, which was also featured on the soundtrack to the break-dancing-themed film Breakin’, reached number 2 on the R&B chart and gained the Bar-Kays their first and only platinum record.

> The Pain Continues

In 1984, the same year that the Bar-Kays earned their platinum record, they suffered another loss when their guitarist, 19-year-old Marcus Price, was shot during an attempted robbery in Memphis. Price was leaving a rehearsal session when three men approached him, demanding his belongings. One of them placed a gun to his back. A struggle ensued, and Price was shot. He died at the Regional Medical Center shortly afterward. His murder remains unsolved.

“He was an aspiring guitar player,” Alexander reminisces. “We put him in the band, because we thought he could bring some youthfulness. He added a little spunk.”

The Bar-Kays then released 1985’s Banging the Wall, which was not particularly successful. The group decided to take a break from releasing records and focus on songwriting.

Tragedy struck again soon with the death of the group’s long-time producer and manager, Allen Jones. Jones, who died of a heart attack, was heavily involved in the band’s career but also in the members’ personal lives.

“We cherished him,” Alexander says. “It was a big loss for us, because he was a friend, mentor, manager, and our producer. He’s the one who taught us that practice makes perfect — that if you continue to work at something continuously, you’ll get better and better at it.”

Several years later, Alexander and Dodson created the Allen Jones/Marjorie Barringer/Bar-Kays Scholarship in Jones’ memory for students who aspire to attend LeMoyne-Owen College.

> Resiliency is Key

Despite the trials the Bar-Kays have experienced through the years — the tragic loss of four original members, the Stax Records bankruptcy, Price’s murder, Jones’ untimely death — they continue to display remarkable resiliency and to create music.

“The Bar-Kays have shown that they can weather the storm,” Walker says. “They have shown that they can stand the test of time. Any artist, whether in a band or solo, should be required to study the career of the Bar-Kays, if you plan to succeed in the music business.”

When the Bar-Kays released their 1987 album Contagious, the group consisted of only three members: Dodson, saxophonist Harvey Henderson, and keyboardist Winston Stewart. Even founding member Alexander had taken a break from the band at this point due to growing fatigue from decades of recording and touring.

The remaining members still managed to reach number 9 on the R&B charts with Contagious’ single, “Certified True.” After Contagious, the group’s contract with Mercury expired and the Bar-Kays took a hiatus until 1994. By then, Alexander had rejoined the group, along with several additional members, and they released an album called 48 Hours. They’ve been playing ever since.

In 2012, the Bar-Kays played at President Barack Obama’s inaugural gala, as well as at the 10th installment of the In Performance at the White House series, along with several other notable Memphis-connected artists this past April.

Dodson just finished filming an independent movie based in Memphis, Alexander is working on a memoir that details his experiences in the music industry, and the group is prepping the release of their next single, “Soap Opera Love.” And the beat goes on.

On Friday, July 5th, Minglewood Hall presents “An Evening with the Bar-Kays.” Doors open at 7 p.m.

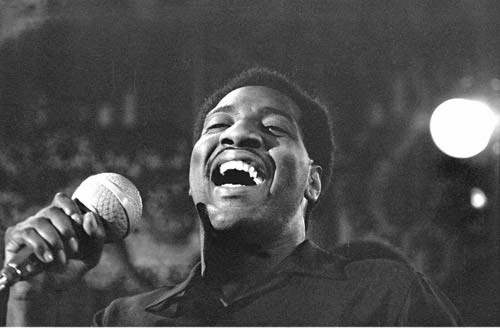

(l) courtesy Specialty Archives; (r) by Jean Pierre Leloir

(l) courtesy Specialty Archives; (r) by Jean Pierre Leloir  Courtesy Specialty Archives

Courtesy Specialty Archives  Courtesy Stax Museum of American Soul Music

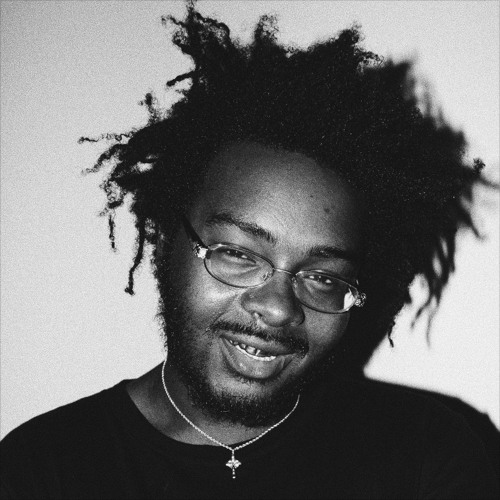

Courtesy Stax Museum of American Soul Music  Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Pierre Jean Durieu | Dreamstime.com

Pierre Jean Durieu | Dreamstime.com