On April 19, 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofman dosed himself with the research chemical lysergic acid diethylamide-25 (LSD). Hofman, a scientist for Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, had synthesized the chemical in 1938, but it wasn’t until he accidentally absorbed some of the chemical through his finger tip five years later that the drug’s psychedelic properties became known. After his self-administered acid test, Hofman became a believer in LSD.

Sandoz brought the drug to the U.S. in the late ’50s, for use in psychiatric studies. Harvard psychology professor Timothy Leary was already experimenting with psilocybin use, and when he discovered LSD, Leary became an immediate convert — and one of the most vocal proponents of the drug’s potential for mind expansion.

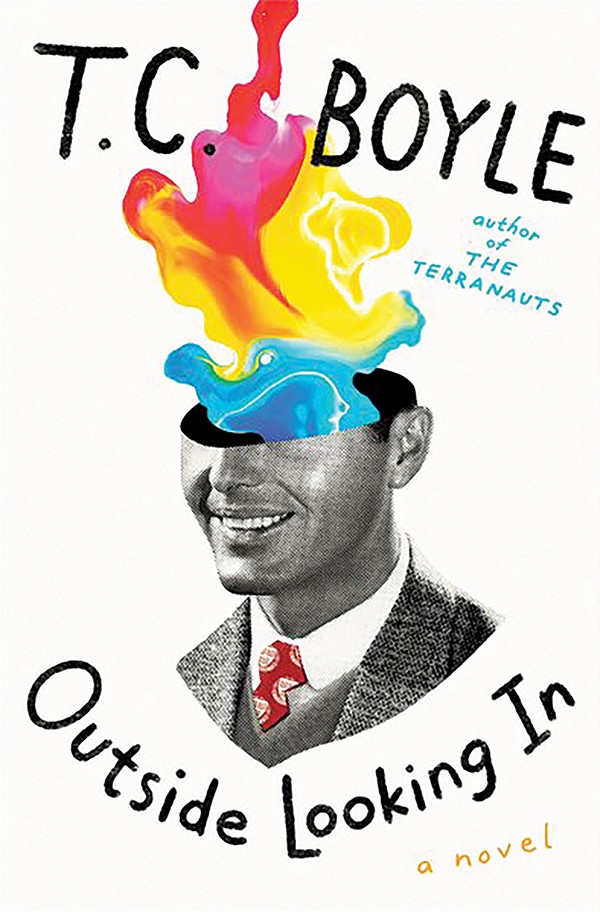

Leary’s experiments, with professor Richard Alpert and a gaggle of psychology graduate students, form the backdrop for the new novel from T.C. Boyle, Outside Looking In (HarperCollins). The novel follows a fictional couple, Fitzhugh and Joanie Loney, as they become enraptured by Leary’s experiments — and eventually pay the price of free love.

Close quarters and social experiments hold a special attraction for Boyle, whose 2016 novel The Terranauts focuses on a fictionalized version of the Biosphere 2 project, an early ’90s experiment in which four men and four women were locked in a glass-walled colony in the Arizona desert. The experiment, in life and fiction, was a disaster; the colony more a petri dish than a home. In Boyle’s newest novel, the close confines are Leary’s estate in Millbrook, where he and his coterie of grad students (and their families) live together. And the social experiment is the group’s game but ultimately failed attempt at perfect mental harmony, what Leary refers to as “group think.”

The novel begins with bliss and broken-down barriers, but a harsh comedown waits in the wings. Fitz and Joanie, at first reluctantly, begin to participate in Leary’s Saturday sessions. And they feel closer than ever, for a time.

But soon enough, Harvard fires Alpert and Leary, and the inner circle moves into Leary’s house and starts calling the drug the “sacrament.” The acid sessions aren’t just on Saturdays anymore.

The group of would-be psychonauts are run out of Harvard. They take up residence in Mexico — at least until the authorities deport them. All the while, the group becomes more in the thrall of Leary and his sacrament. The sleeping arrangements are fluid, and though the mantra is “live in the moment,” jealousy proves to be second nature, even to the psychedelically initiated. What happens in Mexico, apparently, does not always stay in Mexico.

It’s impossible to read Boyle’s patiently plotted novel without thinking of Leary’s group as a cult, with Leary as the charismatic figurehead. Their ideals are worthy, but beyond the communal living and the shared ecstacy lurk jealous spouses, abandoned theses, and neglected responsibilities. And a band of feral teenagers, the children of the psychonauts, roam the halls of the Millbrook estate unchaperoned, while their parents trip in search of universal truths or individual gratification. And it should be noted that Leary never seems to lack for gratification: “This was Tim’s show, Tim and Dick’s, and she was window dressing,” Joanie thinks as she prepares a massive meal for a special occasion. “But he was Tim and Tim always got what he wanted.”

Boyle walks Fitz and Joanie through different stages of enrapture and disillusionment. Their newfound way of life seems like an endless vacation, and Fitz and Joanie can be forgiven for falling under the sway of Leary. Attachments and conformity cause their fair share of misery, to be sure, but they’re necessary pillars of society. Ultimately, Boyle makes the case that Leary’s psychedelic lifestyle is a nice trip, but you wouldn’t want to live there.