When you have declared enemies so fanatic that they will not only risk their lives to deprive you of yours but will pursue such a suicidal end as a glory to be achieved at all costs, how do you arrive at the right sort of disincentives to discourage them? That is rapidly becoming the main theological conundrum of our times, and, as such things go, it is somewhat more compelling than, say, that famous question that medieval scholastics used to ponder: How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

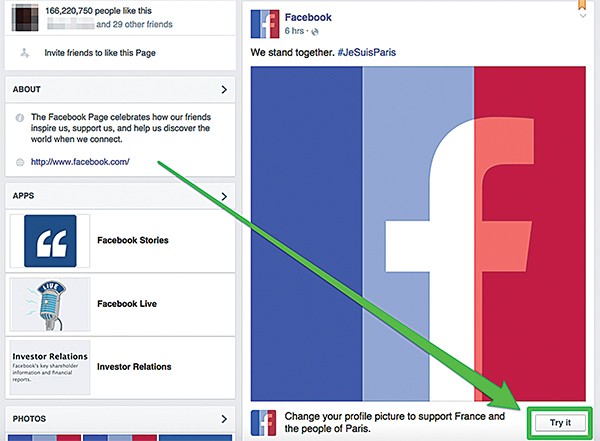

And, unfortunately, as last Friday’s tragic events in Paris most recently demonstrated, the question of the suicide bomber (or suicide shooter or what-have-you) is inescapable. How we answer it when it comes around to the U.S. will, as they say, determine our final grade. It goes beyond politics or statecraft or even religion. It is, in the most literal sense, existential.

So what do we do? None of the instant solutions tendered so far have that Bingo ring to them. Not, for example, Donald Trump’s seat-of-the-pants recommendation that we “take the oil,” the previous raw material the minions of Daesh (the latest name for ISIS or ISIL) are selling on the black market to finance their caliphate. And how do we do that? By “bombing the s**t” out of it at its source — pipes, scaffolding, sand and all.” Oh.

Trump is nothing if not versatile, however; his ex post facto remedy for the carnage in France was that the assassins could have been stopped if only their victims had been packing their own heat. Never mind that he borrowed this from Wayne LaPierre, the sage of the NRA, and that its actual point of origin was probably a 1970s episode of All in the Family in which Archie Bunker advocated that airlines start handing out guns for self-defense to all enplaning passengers.

At the other extreme of possible action, there seems to be no practical way to bargain with the jihadists, who would appear to be insisting on absolute surrender on the part of us infidels — a category that, to judge by events, is virtually all-inclusive: Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Buddhist, secular humanist, trash-talking atheists, and even, it would seem, their moderate co-religionists in the Islamic world, who are as likely to be turned into corpses or sex slaves as anybody else, and who in several well-publicized cases have been forced to pay with their heads, despite their conversion to Islam.

But there, if anywhere, lies the clue to success — not in routine denunciations by fanatics on our side of “radical Islam” (by which, they usually mean, Islam of any persuasion) but in coming to closer terms of cooperation with the governments and societies (Jordan, Turkey, the Emirates, to name several) that practice Islam in a way congenial not only to the Koran and the prophet but to the principle of coexistence in a world of diversity.

That’s not a complete answer, we know, and we’re not talking about trying to line up such actual and potential Arab allies on the firing line as “boots on the ground.” That hasn’t worked out too well. But active cooperation of some sort beats hell out of our trying to become Holy Warriors in our own right.