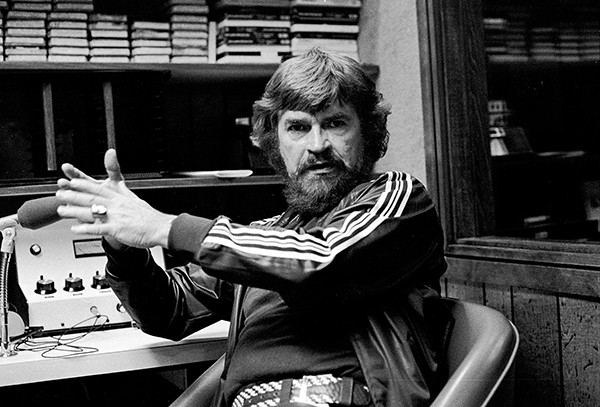

Pat Rainer

Pat Rainer

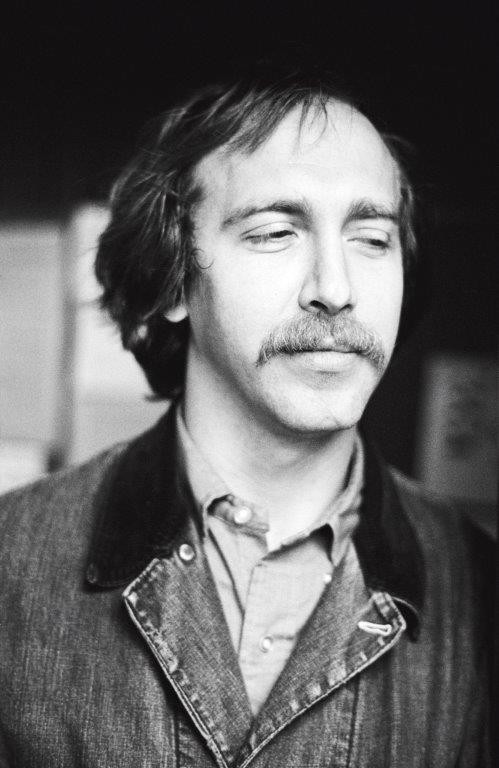

Jim Blake

Blake was at the center of a scene that included Jim Dickinson, Sid Selvidge, Lee Baker, Jimmy Crossthwait, Alex Chilton, Ardent’s John Fry, Knox Phillips, William Eggleston, and Tav Falco, among others. By his side through much of the decade was Pat Rainer, who exhibited her photographs from the era two years ago at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music.

Yesterday I spoke with Rainer, who now lives in California, about Blake’s importance to the scene and his legendary archive of recorded works by the likes of Dickinson, Lesa Aldridge, the Klitz, and wrestler Jerry Lawler, complemented by his formidable library of LPs, comics and books by others.

Memphis Flyer: What happened? Was Jim Blake in ill health?

Pat Rainer: He fell while he was going into his house Friday evening, and a neighbor got an ambulance to take him to a hospital in Wynne, Arkansas. And people there figured out he had a fractured pelvis. The next morning they helicoptered him over to [Regional One], and he’d been there since Saturday. But then this afternoon he became unresponsive. They couldn’t revive him.

All because of a fractured pelvis?

You know, he had had heart bypass surgery in the fall of last year. And he had done pretty well since then. But in the past month or so, he’d been complaining about having problems with his balance, and having vertigo. On Friday, he was trying to carry a bunch of stuff in his house and he fell. I assume he was carrying comic books or records. Or both. I mean, it’s pretty poetic if that’s what he was carrying, but for all I know he was carrying groceries.

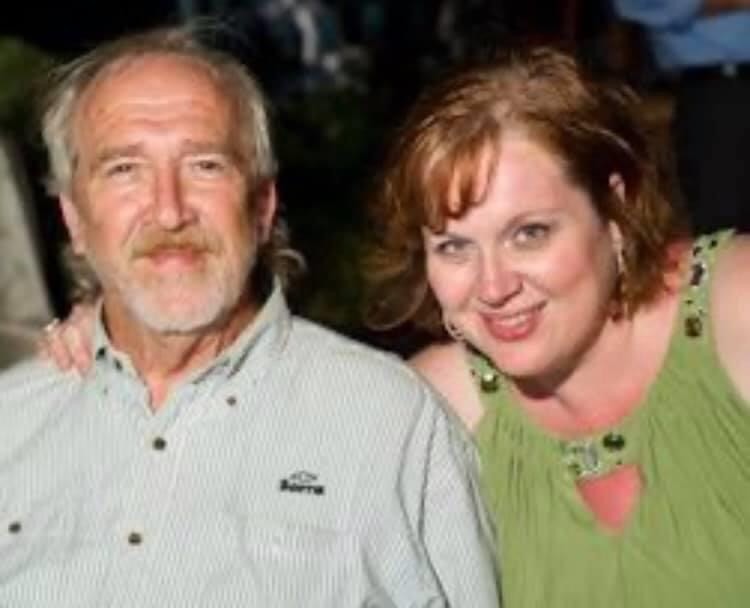

courtesy Mesmery Blake

courtesy Mesmery Blake

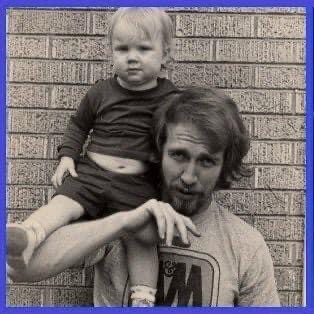

Jim Blake and daughter Mesmery

This was at his home near Wynne, Arkansas?

Yes. Jim’s mother moved to Arkansas because her family was there. She was from Cherry Valley. Jim moved there when he left L.A. in the late 80s to take care of his mom when she was in failing health. Then his older brother bought a place there later.

You may have worked with Jim Blake longer than anyone in Memphis from that time.

I’ve known Blake since ’68 maybe? ’67 or ’68. I worked for him at Atlantis, which opened in ’68. I don’t know what you know about Atlantis, but it was a trip. That was the predecessor to the Yellow Submarine record shop. It was a house on Poplar, an old brick bungalow. And every room was devoted to a different kind of retail store. There was a record store, a comics store, Mike Ladd had a guitar shop, and there was, of course, a head shop. And somebody built a big light organ and hooked it up to a stereo, and we had all these headphone posts in there. You could sit in there and put the headphones on and watch the light show.

courtesy Pat Rainer

courtesy Pat Rainer

Pat Rainer at Graceland the day after Elvis died

He published an Atlantis newspaper, and he promoted a concert with Spirit at the auditorium, and then he did another one with Donovan. Atlantis preceded Yellow Submarine. In the interim, we had a falling out for a minute because I left him and went to work at Poplar Tunes. How dare I leave him! That’s the story of my life with him. Periods of being estranged because you didn’t do what Jim thought you ought to do, because that’s just the way it was. Then I went back to work for him and Nancy (his ex-wife) at Yellow Submarine. That was when he had what was first called Tennessee Roc newspaper, and then after that it was the Strawberry Fields newspaper.

He had pretty strong opinions. Kind of a firebrand, it seems?

Yeah. We were very passionate about music. That was our main thing. And he did what he could do to spread the word about stuff we heard and thought was important. Everything from David Bowie to Lou Reed to Rod Stewart. With the help of our friend Grover, he got Bowie to do a live interview on FM 100 with Jon Scott, and that really did break Bowie in America. We were into Bowie, let me tell ya. I loved Bowie, but Blake and Grover were cuckoo for coco puffs over him!

So Barbarian Records began while you were working at Yellow Submarine, when Blake decided to put out a record by Jerry Lawler, the wrestler?

Jim Dickinson really gave Blake the confidence and the idea that he could take Lawler into a studio and he could make a record. Dickinson said, “You know, you could make a record on Lawler and sell them at the matches,” and you could see the light go off over Jim’s head. He and I used to take Lawler’s records to the Coliseum and sell ’em in the stands, just walk up and down the aisle and sell them. When Lawler was a bad guy, they would buy ’em and break ’em! And when he became a good guy, they would take ’em and try and get ’em autographed.

I think working with Lawler meant the most to him. But he was really thrilled to work with my friend Randy Romano, who we called Sabu La Teuse. He was a gay white man who sounded like a young Black woman. And I think just being in the studio was what he loved, you know? All the musicians that would come work for him, it was just a blast.

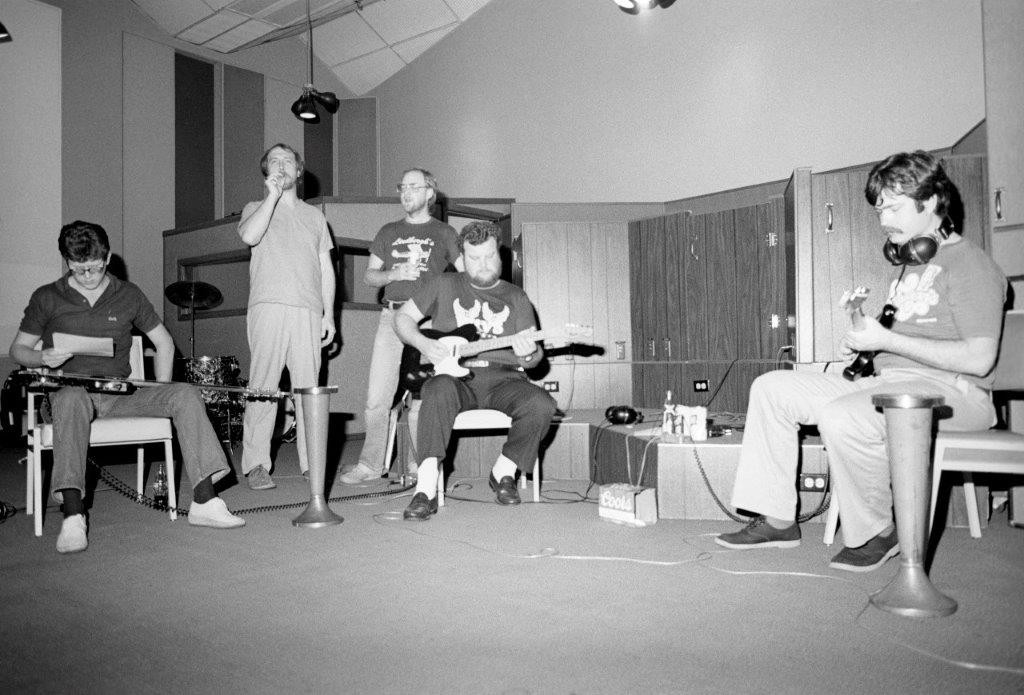

Pat Rainer

Pat Rainer

Jim Blake smokes a joint while musicians prepare for a recording session, 1970s.

In addition to the handful of records he put out in the ’70s, he had a lot of unreleased recordings, didn’t he?

Yes, and I’d been working with him really hard for the past four or five years to get him to get those tapes out, so we could reissue all the Barbarian stuff on Omnivore Recordings. And he would always start the conversation with, “But I’ve got all these unfinished tracks on Alex Chilton and Sabu and Dickinson!” I’m going, “Jim, can we reissue the stuff that’s already been released? That”s been mixed and mastered? Then we can look at other stuff.” But there was always some reason why he couldn’t get to it.

Just the mindset of thinking he would go in and tweak something from 40 years ago, it’s mind-boggling.

Uh, yeah, like, “I’ve just gotta finish that track, get that one guitar overdub.” [laughs]

courtesy Mesmery Blake

courtesy Mesmery Blake

Jim and Mesmery Blake

Robert Gordon went over there and helped him get the door open to the storage trailer where he had all the Barbarian masters. His and Nancy’s daughter Mesmery and I have been trying to get out there and get into it. Then he had to have that heart surgery. And then the pandemic. Robert sent me some shots he took, of piles and piles of stuff in his trailer. It looks very familiar to me. I lived through that for so many years with him. It started off small, and then when he relocated from his small house over there by Memphis State, he moved to a bigger home out there in Raleigh. And he built wall to wall record shelves, where he had to walk through there like a maze. You had to walk sideways. After that, he and I kind of fell out again, so I haven’t seen any of it over there in Arkansas.

It sounds like an amazing library, not just of Barbarian material, but in general.

He collected records and comics and never got rid of any of ’em. He collected books and posters and artwork.

Did he live alone out by Cherry Valley?

Yeah. He’s been living alone out there for a while. He has a cousin that lives down the road. His brother passed away a while ago. For years and years, we’ve called Mesmery the Barbarian Heiress. She’s his only daughter. Jim said when he first looked at her he was mesmerized, so she’s named Mesmery. She moved to Oregon to work in the wine industry and she’s done very well for herself there.

Of all the stuff he worked on, what meant the most to him?

I think anything he worked on with Dickinson. Dickinson was his mentor, like he was mine.

Did Jim Blake do much into the ’80s?

He moved out to LA in the early 80’s to work with Jon Scott, who was doing independent record promotion. Jim and Jon put out a tip sheet for radio called “Scott’s Tissue” with news about new music that went to radio programmers around the country. They also worked with a band called DFX2. They got them signed to MCA and had a record come out that was quite good.

Then he kinda transitioned, and he was working for Jerry Lawler for quite some time. He was driving to Memphis from Cherry Valley three or four days a week, to work for Lawler. Even recently. In fact, Lawler fixed up a place for him to stay at his house, after he got out of the hospital from having that heart surgery. You know, when Jerry was just a kid, Blake would pay him for his artwork. Jerry would draw stuff for our newspapers; he painted the front of the Yellow Submarine with a scene from a comic book. Jim always tried to encourage Jerry. We used to call him the human Xerox machine. Lawler could look at anything and reproduce it. And making those records, Jim was really ahead of his time doing that.

A memorial service in celebration of Jim Blake’s life will be held in Memphis in the near future, according to Mesmery Blake.