“Jared McLemore is live on Facebook.” Those who clicked immediately saw a dark street scene with trees in the background. Then, McLemore, shirtless, rushes into the frame and sits crosslegged, his expression strangely blank. He pours gasoline over his body from a red can. Voices come from offscreen as he fumbles with matches. A second body rushes in, tackling him, but it’s too late. The frame is filled with flames. Fully engulfed, but eerily calm, McLemore runs off screen. The screaming begins.

***

Rock-and-roll came naturally to Alyssa Moore. Her parents were punk rockers in the Antenna scene of the 1980s. She picked up the guitar and wrote her first song at age 8. At 13, she played her first gig — a kid’s birthday party. Music became her passion, her escape from reality. “I’ve had family problems my whole life,” she says. “When I turned 14, 15, it was the worst it had ever gotten. They were fighting constantly. … My dad was gone. My mom was so depressed that she would just come home every day and go to sleep.”

Up until the ninth grade, she had been an A student. After the divorce, her grades faltered. Two months into her junior year, Moore dropped out. “I got my own apartment and started living as an adult. I’ve been living in Midtown since then.”

She met Will Forrest when she was 15. “I remember hearing her music on her MySpace at the time,” he says, “and thinking she was a pretty rad musician. We wound up both frequenting the open mic at Java Cabana and started playing music together.”

The two started dating. They recorded their first album with engineer Kyle Johnson at Rocket Science Audio. “I always wanted to be a rock star,” she says. “Every night I would go to bed, put on my headset, and listen to whatever female musician I wanted to be at the time: Courtney Love, Chrissie Hynde, whoever. Being a rock star is awesome. But I wanted to be able to do what Kyle did.”

Johnson became her mentor. “He just trusted me so much and had so much confidence in me,” she says. “Instead of teaching me everything, he said ‘Here’s the keys. Go play. The only way you’re going to figure this out is if you do it a million times.'”

After about five years, Moore and Forrest’s romantic relationship cooled, but their musical collaboration remained strong. Their new band was called Strengths. Their music was a mix of punk, metal, and math rock, with savage guitars and sudden time changes. It was smart and complex. Then, in November 2014, she met McLemore.

“He introduced himself after a Strengths show,” recalls Forrest. “He’s an excessive personality, talks a mile a minute. He was really funny. He wanted to dominate the conversation and be the center of attention.”

The day after the show, he sent Moore a Facebook friend request. “He was working at Ardent; I had started doing sound at Murphy’s. I was a studio rat at that point. It just made sense for us to get together.

“When we started dating, he asked a lot of questions. He was very intelligent. He had an imagination that I was drawn to. Because I was so fascinated with music and with recording, and he was as well, that was essentially our relationship for the first eight months.”

McLemore told Moore that he had been diagnosed with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. “His mental illness didn’t scare me,” Moore says. “I knew what depression felt like, and I knew that it causes you to do and say things that you wouldn’t otherwise do. I watched my mother, in my childhood, be super depressed, and I saw when she came out of it, she blossomed. This is a guy who has had shitty luck his entire life, I thought. He’ll be okay, I just have to prove to him that somebody can love him with a mental illness.”

Mitchell Manley met McLemore when they were 17 years old. “When I was living in Milan and was playing in bands with him, I knew he had a lot of personal trauma.”

McLemore was married while in Jackson. But after about seven years, his wife left him in the middle of the night. “None of his friends ever saw her again,” says Manley. “Shortly after his wife divorced him, he attempted suicide. He tried to shoot himself, but the gun jammed. They airlifted him to Memphis and immediately put him into mental health treatment. Then he tried to start a better life.”

Moore says she did her best to help McLemore. “As he opened up to me about his illness and the things he had done about his illness, I was like, ‘You need to be on medicine. Don’t be ashamed.'”

Moore says that while they were together, they smoked marijuana but didn’t take any other drugs. With her family’s painful history of alcoholism, Moore didn’t drink, and for a while, McLemore didn’t either. “He admitted to me that he had an Adderall addiction from the ages of 22 to 28. He was prescribed Adderall, because doctors thought he had ADHD instead of bipolar disorder. That was a big mistake. They gave speed to a psychopath.”

After five months, the couple moved into a Midtown guest house. “If something went wrong, he would say ‘I’m going to kill myself.’ He would break down and cry a lot, and I would hold him and console him.”

Strengths was one of the tightest bands in Memphis, but McLemore convinced Moore and Forrest that something was wrong. Forrest says McLemore suggested starting a new band. “He offered the solution that he would play drums, and we could be super tight. But it wound up being a way less-functional band, and it fell apart.”

The new band played one show. “After that show, Jared said, ‘Look, I’ve tried to be friends with Will. I just can’t do it.’ So, we talked to his therapist about it, and even his therapist sided with him. He said it was strange for me to be in a band with my boyfriend from high school. She convinced both of us that me being friends with Will was a bad idea. … Looking back, [Jared’s] motive was to isolate me from my friends.”

“This trajectory is very common,” says Dr. J. Gayle Beck, professor of psychology at the University of Memphis. “This pattern almost ensures that she has less social support and few places to turn when stressed.”

***

In February 2016, Moore and McLemore were working together in the studio. “I don’t remember what caused the argument, but he stood up, grabbed my wrist, pulled me up, dragged me to the bathroom, closed the door and locked it behind us. He pushed me to the corner, and pushed me down on the ground. He held my hands back, and said ‘Okay, this is it. Now you’re going to die.'”

Trapped against the wall in the bathroom, Moore talked McLemore down from murder. “I scraped my hand against the wall. I remember looking at it and thinking, ‘Well, I’m bleeding because of my boyfriend. But it’s so tiny. Surely this means nothing. He just had a bipolar episode.'”

Moore told no one of the incident. “It is shameful to say, ‘Hey, the man I love locked me in the bathroom and tried to kill me.’ You feel like an idiot.”

Terror and threats became regular occurrences. “He was very smart about not leaving bruises in obvious places,” she says. “To the day he died, he would say, ‘I never beat you up,’ but I would say that he did, because that’s what it felt like.”

Beck says there is a broad range of abusive behaviors beyond beatings. “There is a common belief that Intimate Partner Violence [IPV] is only abuse if it entails hitting and punching. IPV subsumes physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Sometimes abusers will threaten to kill the victim and later say, ‘I was just angry — I’d never do that.’ Being threatened with a weapon is abuse.”

“People ask, ‘Why did you stay with him?'” says Moore. “I beg that they look at their own relationship and imagine their partner turning on them and wondering how long it would take for them to be like, ‘Okay, I gotta get out.'”

***

The first week of August 2016, Moore got a rare moment away from McLemore. She used the opportunity to contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline. “At that point, when you have somebody else validate you like that, you kind of freak out a little bit. I wasn’t quite prepared to make a plan to leave at that point. But having someone else tell me, ‘Yes, you’re being abused. You need to leave’ is so powerful.”

Two weeks later, McLemore accused Moore of flirting. “He said that I’d been slut dancing to this band. My denial of it sent him over the edge. I was making dinner when he decided to attack me.”

Alyssa Moore

Alyssa Moore

The kitchen in the Midtown guest house Moore shared with McLemore became the scene of an attack.

At knife point, he forced her into the bedroom. “He said, ‘Take your clothes off. Now.’ I just kind of looked at him, because he had never done that before. He said, ‘You know what’s going to happen. Do it.’ And he has the knife in his hand. So, I get naked, because I have to. He comes over to me and gets on top of me. He doesn’t rape me, other than what he’s already done by making me get naked. He grabs my neck and holds my face down. He chokes me. Then he stops, lets go for a minute, and watches me. Then he does it again a second time. Beyond that, my memory blacks out. I disassociated a little bit. I know at some point he ran, but he didn’t take my phone with him, so I called 911.”

The police took the report and told her to find another place to stay. Moore went to her mother’s apartment. “I had to tell her everything.”

Moore informed her friends that McLemore was on the run from police. Two days later, musician Josh Stevens saw McLemore walking on Madison. “At this point, he had either given up and he authentically wanted help, or he just couldn’t run any more and wanted somewhere to recharge. We took him back to the house. He was very docile.”

The next day, Stevens’ girlfriend and McLemore’s cousin took him to the Memphis Mental Health Institute. Instead of checking himself in to the hospital, McLemore bolted. Stevens rushed to Moore’s side. They called the police. “Then we saw Jared.”

McLemore started running towards Moore. “He was literally going to kill her,” says Stevens. “I saw it in his eyes. …The last thing I remember my friend Jared saying to me — and I say this because he wasn’t my friend after this — was ‘I should have killed you and your girlfriend last night when I had the chance.’ We tussled. I got him down, but he got away.”

McLemore stole Moore’s car. As he was driving away, Moore’s father Mike was arriving. He recognized McLemore and followed him. McLemore stopped, got out of the car, and the two fought. Again, McLemore got away. Meanwhile, the police had arrived. Moore says they were less than helpful. “I told them what had happened the night before, and they just kept hushing me. They didn’t look up at all. No eye contact or anything. They didn’t tell me what to expect, where he was going, nothing.”

McLemore returned to the house and gave himself up to police. He was committed to the Western State Mental Health Institute in Bolivar.

“I think that we expect too much from law enforcement in this domain,” says Beck. “It takes a woman [on average] six or seven attempts to successfully leave an abusive/violent romantic relationship. The implication of this is that the police will be called multiple times to her address. If they ask him [or her] to leave and the couple reunites, they have done all that is within their power to do. We cannot rely on the police to ‘solve’ the DV [domestic violence] in Memphis.”

After he was released from the hospital, McLemore was taken to jail. His mother bailed him out, and he was put on diversion. He went to live with her in Milan, Tennessee. He was forbidden to contact Moore and fitted with a GPS ankle bracelet.

In early September, Moore decided to make her story public, inspired by other women in Midtown who had called out their abusers on Facebook. “They were not saying these things to villainize their abusers and rapists. They were saying things to give courage to people who had had these things happen to them. Tell them, this happened to me, too. … In retrospect, I did it exactly wrong. I should have posted every picture I had, every screenshot that I had. I shouldn’t have given him any benefit of the doubt. Some people who are raping, abusing, hitting, being violent — sociopathic people — they cannot change their behaviors. Why should we not call them out?”

Moore’s Facebook post detailing her abuse at McLemore’s hands was widely seen and shared in the Midtown music community. One of the women who saw it was Jessie Honoré, a domestic abuse survivor who had become an advocate for women in similar trouble. “I had friended [Alyssa] because she is so great. I reached out to her. She’s younger than me. I’m a mom of two. I felt like I could offer her some advice.”

Honoré invited Moore to an online support group for Memphis women who have been victims of intimate partner violence. “Abusive relationships make you question your own judgment and your own gut instincts,” Moore says. “So, having a group to nurture you while you’re coming out of that fog is invaluable.”

The months that followed were free of abuse, but Moore faced new complications. She was stuck paying for rent at both the studio and her home. Moore had been advised to buy a gun, but she wasn’t comfortable with firearms. Instead, she got a knife for protection.

For a while, McLemore seemed to be getting better. He expressed regret publicly and privately. But it didn’t last. He moved back to Memphis, and the threats resumed. “He was sending and posting pictures of himself with a gun in his mouth,” says Moore.

Jared McLemore’s messages.

After being contacted by multiple concerned people, Moore eventually texted McLemore. “I sent a message that said, ‘Don’t talk to me. Get your shit together. Stop circulating these pictures. Don’t kill yourself. Things aren’t going to be awful forever.’ He sent a bunch of apologies. I said ‘Thanks, I don’t want to hear any more from you.'”

The contact turned out to be a mistake. “Throughout March and April, he would contact me. It was suicidal stuff, so I would call the police. I was not dealing with him any more.”

On the evening of May 9, 2017, Moore was washing dishes in her apartment. She looked up to see McLemore staring at her through the window. McLemore scraped the screen with something metallic. It was her knife. “He had obviously broken into my house or my car to get it, because those were the only places I ever kept it. He told me he had a gun. He said ‘I ought to kill you.’ That’s when I ran into the bathroom and called 911 again.”

When police arrived an hour later, McLemore was gone. “I told them many times that he was on probation, that he sent me pictures of the gun in his hand.” The police seemed skeptical of the situation. They told Moore that the Domestic Violence unit would call her the next day. The call never came. “I was afraid to go outside,” says Moore. “I didn’t think he had any reason not to kill me at this point.”

Desperate, she made another Facebook post detailing McLemore’s threats. “My intention up until the day he died was to get him into a hospital. I kept thinking, ‘he only wants to kill me because he’s depressed.'”

On Thursday, May 11th, Moore went to the Family Safety Center to file a restraining order against McLemore. She was told it took two hours to process, and the center was closing in an hour. That night, Moore got a message from McLemore’s roommate. “The police had shown up, searched the house, but they couldn’t find the gun,” she says. “Jared was acting sane and normal, so they didn’t take him anywhere. This was after the Facebook post, after hundreds of people had called the police. They showed up to his house, searched the place, and left. They didn’t take it seriously, at all.”

The next morning, Moore returned to the Family Safety Center. “Through them, I was able to get a warrant for his arrest,” she says. “Eventually, I went to work. I figured the police were coming.”

***

Friday, May 12th, at Murphy’s was a triple bill. Paul Garner had contracted with Moore to record his band, Aktion Kat. “We booked the show about a month prior. We respected Alyssa as a recording artist, and we knew she would do a great job.”

Garner, an activist at the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center, learned about McLemore from the Facebook post. “This was a person who had done everything a victim is told to do and was essentially shrugged off.”

Moore had asked Forrest to come to the club. “There had been so many times when he would threaten to show up,” he says. “I would go up there a lot of nights and hang out. I was really exhausted, so I said I would go next door and lay down for a minute. I kind of dozed off.”

Murphy’s staff was aware of the situation, so Moore says she felt safe. “I thought surely the police were going to come and arrest him. But about 10:30, I got a message from him: ‘I have a warrant out for my arrest. I didn’t assault anybody. I must die.’ Then about an hour later he showed up.”

Aktion Kat was setting up when McLemore walked in and made a beeline for Moore. “He was shirtless, and he was already covered in gasoline. He grabbed my arm and rubbed it down a time or two and nodded. He had told me, ‘I’m going to cover myself in gasoline and set myself on fire. That’s how I’m going to die.’ He said goodbye, and he kissed me. Then he went outside.”

Garner chased McLemore out the door, followed by Moore and other people. No one knew he was broadcasting his suicide live on Facebook. “By the time I got outside, he was on the other side of the street, assuming the crosslegged position and pouring the stuff over his head. I had a couple of seconds to try to prevent him from doing what it was obvious he was about to do.” He charged McLemore and tried to kick the matches from his hands. “As soon as I made contact, I felt the heat.”

Moore was at the door. “The flames shot up 10 feet high. At this point, I don’t see Paul. All I see is Jared on fire.”

McLemore silently stood up and ran toward Moore. Garner was on fire too. “I saw the little grassy field next to the P&H and thought, maybe that grass is wet. I was rolling around over there until my friend Scott Prather ran across the street and jumped on me and put me out.” Moore waited until two other people ran in before she closed the door. “There was a moment when I was on one side of the door, and Jared was on the other side of the door. I was staring him in the fucking face while he was on fire. I was trying to lock the door, but the heat was so intense.”

Moore fled into the bar. McLemore burst through the door. “I saw Steve [Wacaster] coming out with the fire extinguisher,” she says. McLemore crumpled to the ground as Steve sprayed him with the fire extinguisher. “People were pouring water and beer, trying to put him out. It was nauseating.”

Forrest was awakened by a call from Moore and ran into Murphy’s. “Jared was laying there, half melted. He saw me. I could kind of hear an eagerness in his voice when he saw me. He said, ‘Will, help me. Will, help me.’ The smell of him. … I will never forget that.”

Outside, Moore was in shock. “Some woman — I don’t even know who it was — grabbed me and hugged me and said, ‘You don’t have to be afraid any more. I’m not letting go of you.’ It was exactly what I needed right then. I wish I knew who it was.”

***

The horrific video quickly went viral. Within hours, it had spread to England, where The Sun tabloid published it on their website.

Garner was taken to the hospital with second and third degree burns on his calves and hands. He was briefly kept in the same room as McLemore, who died about eight hours after the fire.

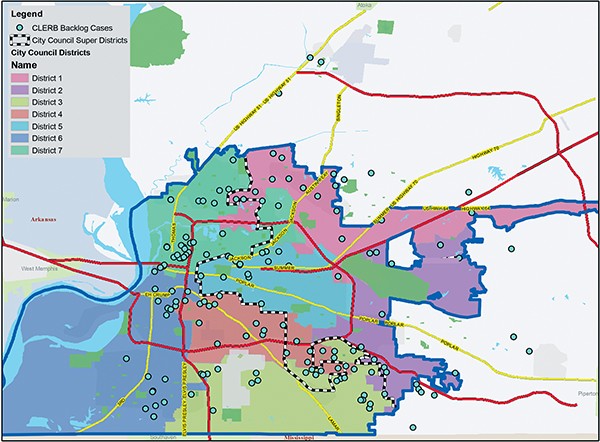

“I really wanted to highlight that I don’t like the whole hero individual narrative that they were trying to hit me with,” he says. “I wanted more to be focused on, why did this happen? This person had been reported multiple times. He had been active on Facebook, and when people were tagging police and asking why they didn’t do anything, he was commenting on those threads. As someone who has experienced police surveillance in recent years, I know they have social media tools like Geofeedia that they are using to track us and where we are having protests. I wish that same kind of energy would go into a legal investigation into someone who has been reported as a threat by other folks.”

That night, Jessie Honoré started a GoFundMe campaign for Moore. “She was very insistent on the details being correct, and very insistent on not asking for a single penny more than she would need. We broke it down. What if we were able to raise enough money so you didn’t have to go to work for 30 days? What is six months of trauma therapy? I reached out to a local therapist and asked what she would charge Alyssa for therapy.”

The goal Honoré settled on was $6,300. More than $25,000 rolled in the first day. “That was just Midtowners,” says Honoré. “Then it went viral across the country the next day.” When the GoFundMe was finally closed after a month, more than $42,000 had been raised. A benefit concert at Memphis Made Brewery raised an additional $3,000. “It changed her life,” says Honoré. “That’s an awesome thing that came out of this. People give a damn.”

***

“After the fact, it’s an easy conclusion to state that Jared’s mental health was a factor. I would not draw this conclusion,” says Beck.

Three American women are killed by their intimate partners every day. A 2006 study by the Violence Policy Center estimated 1,000-1,500 murder-suicides happen annually, the vast majority of which involve men killing their intimate partners. A 2015 study by Everytown for Gun Safety found that 57 percent of mass murderers have a history of domestic violence. If Moore had not made the community aware of her plight, and if people like Garner and the staff of Murphy’s had not been ready to respond so quickly, many others could have died.

At the University of Memphis, Gayle Beck runs the Athena Project, a mental health research clinic for victims of IPV. “The emotional aftermath of IPV varies by the individual, and so there is not a one-size-fits-all approach that we can advocate for every woman,” she says. Common psychological scars from IPV include Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. “The Athena Project offers cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD stemming from IPV. All of the services are free and completely confidential. If a reader wants to learn more, they can phone me at (901) 678-3973.”

“After making my Facebook post, I had so many people privately message me with their own stories. They didn’t want to go public with them. They just wanted to share their stories with someone.” says Moore. “Abuse comes in so many forms. … It’s not always beating. It’s not always this spectacular, but I guarantee that every other person who has been abused feels as crappy as I do about it.”

Alyssa Moore

Alyssa Moore

Saniphoto | Dreamstime.com

Saniphoto | Dreamstime.com