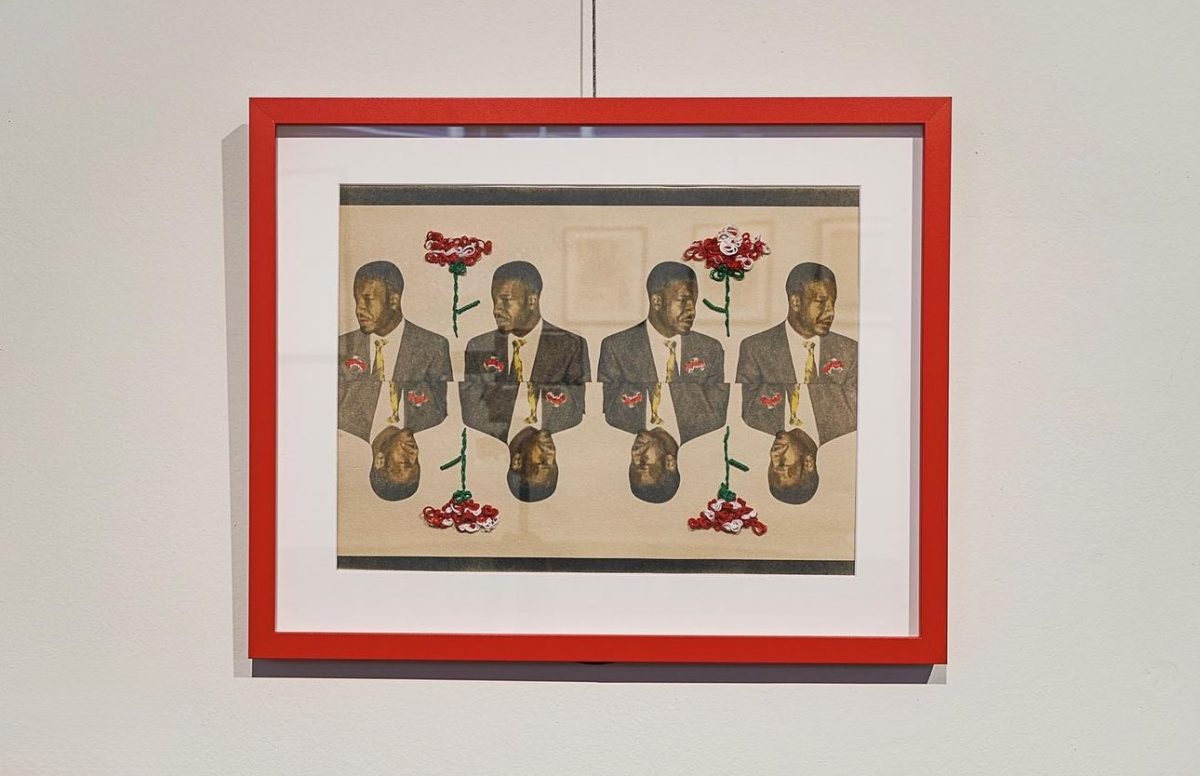

Remembering

Ernest Withers

One of the great serendipities I’ve experienced as a

journalist was the decision by former Memphis Magazine

editor Tim Sampson back in 1993, on the 25th anniversary of

the death in Memphis of Dr. Martin Luther King, to use as the centerpiece

of an anniversary issue an archival piece of mine, along with pictures by the

great photographer Ernest Withers.

Uncannily often, Withers’ photographs directly illustrated

specific scenes of my narrative, which had been written originally on the day

after the assassination and concerned the events of that traumatic day. It was a

little like being partnered with Michelangelo, and I was more than grateful.

The publication of that issue led to an invitation from

Beale Street impresario John Elkington for Withers and me to collaborate

on a book having to do with the history of Beale Street, and the two of us

subsequently spent a good deal of time going through the treasure trove that was

Withers’ photographic inventory.

For various reasons, most of them having to do with

funding, the book as envisioned never came to pass (though years later Elkington

published a similar volume), but the experience led to an enduring friendship.

One day, when I was having car trouble, Ernest gave me a

ride home, from downtown to Parkway Village, the still predominantly white area

where I was living at the time, just beginning a demographic changeover. At the

time it appeared as though it might become a success of bi-racial living, and we

talked for some time about that prospect.

That very evening, Ernest was a panelist on the old WKNO

show, Informed Sources, and, instead of focusing on the subject at hand,

whatever it was, chose to discourse at length on the sociology of Parkway

Village. Watching at home, I was delighted – though the host and other

panelists, intent on discussing another subject, one of those pro-forma

public-affairs things, may not have been.

They should have been. This was the man, remember, who

documented the glory and the grief of our city and our land as both passed from

one age into another, which was required to be its diametrical opposite, no

less. Ernest saw what was happening in Parkway Village as a possible trope for

that, and whatever he had to say about it needed to be listened to.

Sadly, of course, the neighborhood in question was not able

to maintain the blissfully integrated status that Ernest Withers, an eternally

hopeful one despite his ever-realistic eye, imagined for it.

As various eulogists have noted, last week and this,

Withers not only chronicled the civil rights era but the local African-American

sportscape and the teeming music scene emanating from, an influenced by black

Memphians.

He was also, as we noted editorially last week, a family

man, and it had to be enormously difficult for him that, in the course of a

single calendar year while he was in his 70s (he was 85 at the time of his

death), he buried three of his own children.

Among my souvenirs is a photograph I arranged to have taken

of Ernest Withers with my youngest son Justin and my daughter-in-law

Ellen, both residents of Atlanta, on an occasion when they were visiting

Memphis a few years back. Happy as they were with the memento, the younger

Bakers expressed something of a reservation.

What they’d really wanted, explained Ellen, a museum

curator who was even then, in fact, planning for a forthcoming Withers exhibit

in Atlanta, was a picture of the two of them taken by the master.

Silly of me not to have realized that. To be in a picture

by Ernest Withers was to become part of history – a favor he bestowed on legions

of struggling ordinary folk as well on the high and mighty of our time.

Remembering Kenneth Whalum Sr.

There was a time, before Mayor Willie Herenton became the

acknowledged alternative within the black community to the Ford family’s

dominance, that councilman Kenneth Whalum was a recognized third force to reckon

with.

jb

jb

The Rudy Williams Band led Ernest Withers’ funeral procession down Beale on Saturday.

Rev. Whalum was both the influential pastor of Olivet

Baptist Church in the sprawling mid-city community of Orange Mound and the

former personnel director of the U.S. Postal Service, locally. In effect, he had a foot planted

firmly in each of the two spheres that make up the Memphis political community.

That fact made him a natural for the city council during

the period of the late ’80s and early ’90s when the era of white dominance was

passing and that of African-American control was dawning.

During the 1991 council election, Whalum, along with Myron

Lowery, achieved milestones as important in their way as was Herenton’s mayoral

victory, taking out long-serving at-large white incumbents Oscar Edmunds and

Andy Alissandratos, respectively.

Whalum was uniquely able to serve both as a sounding board

for black aspirations and a bridge between races and factions on the council. He

was a moderate by nature, though sometimes his preacherly passions got the best

of him and he sounded otherwise. Something like that happened during a couple of

incendiary sermons he preached during the interregnum between the pivotal

mayor’s race of 1991 and Herenton’s taking the oath in January 1992 as Memphis’

first elected black mayor.

Word of that got to me, and I was able to acquire a

recording of one of the incriminating sermons. I had no choice but to report on

it, and – what to say? – it made a bit of a sensation at the time, no doubt

limiting Whalum’s immediate political horizons somewhat.

It certainly limited the contacts I would have, again in

the short term, with a political figure that I had previously had a good

confidential relationship with. Whalum’s sense of essential even-handedness

eventually prevailed, however, and we ultimately got back on an even keel.

To my mind, in any case, Whalum’s outspokenness never

obscured his essential fair-mindedness, and his occasional prickliness was more

than offset by his genuine – and sometimes robust – good humor.

There are many ways of judging someone’s impact on society,

and one might certainly be the prominence of one’s offspring. In Rev. Whalum’s

case they included the highly-regarded jazz saxophonist Kirk Whalum and the

councilman-minister’s namesake son Kenneth Whalum Jr., a school board member and

an innovative pastor himself — so innovative in his wide-open 21st-century

style as to cause a generational schism involving Olivet church members. That

would result in two distinct churches, one led by the senior Whalum, one by

Whalum Jr.

Kenneth Whalum Sr. had been something of a forgotten man in

local politics since leaving the council at the end of 1995 (he would also run

losing races for both city and county mayor). But he got his hand back in

briefly during last year’s 9th District congressional race, making a

point of endorsing Democratic nominee Steve Cohen, who ultimately prevailed.

Appropriately, Rep. Cohen took the lead, along with Senator

Lamar Alexander, on behalf of a congressional resolution re-designating the

South 3rd Street Post Office in honor of Whalum, closing a cycle of

sorts and forever attaching the name of Kenneth T. Whalum Sr. to one of the

city’s landmarks.

Political Notes:

Kenneth Whalum Sr.

–Congressman Cohen was the target recently of what many local Memphians report on

as a “push” poll taken by random telephone calls to residents of the 9th

District. Purportedly the poll contained numerous statements casting Cohen in a

negative light before asking recipients who they might prefer in a 2008 race

between him and repeat challenger Nikki Tinker.

(At least one person called recalled that the name of

Cohen’s congressional predecessor, Harold Ford Jr., now head of the

Democratic Leadership Council, figured in a triad of potential candidates being

asked about.)

–Early voting is now underway in the four city council

runoffs that will be determined on November 8th.

Those involve Stephanie Gatewood vs. Bill

Morrison in District 1; Brian Stephens vs. Bill Boyd in

District 2; Harold Collins vs. Ike Griffith in District 3; and

Edmund Ford Jr. and James O. Catchings in District 6.

Courtesy of Jay Etkin Gallery

Courtesy of Jay Etkin Gallery

Alex Greene

Alex Greene

jb

jb