When you’re with Memphis songwriters and John Prine comes up, you can tell he’s made an indelible mark on them. Last year I spoke with Keith Sykes, who recited Prine’s lyrics off the top of his head. “The first words out of his mouth, professionally speaking, were: ‘While digesting Reader’s Digest in the back of a dirty bookstore, a plastic flag with gum on the back fell out on the floor. I picked it up and wiped it off and slapped it on my window shield. If I could see old Betsy Ross, I’d tell her how good I feel.’ You ask what makes a good song. Well, when you hear something like that the first time, you don’t think. You just know this is good. It’s contemporary, even today. And that was on his first record, that he cut in Memphis — at Chips’ [Moman] studio, American.”

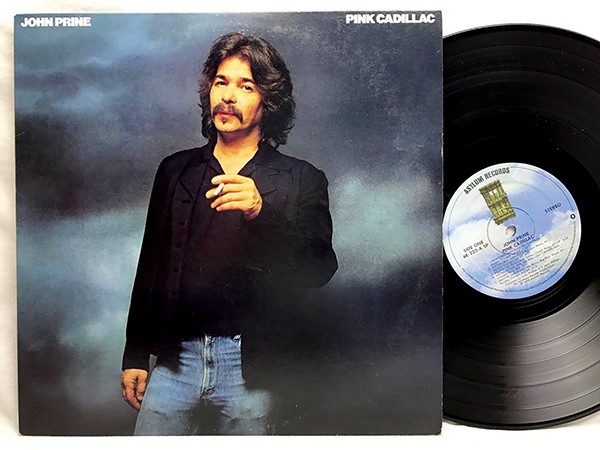

Sykes added, “He also did Common Sense here, and he did Pink Cadillac here. He’s done a bunch of stuff in Memphis, and he loves it down here.”

Diane Duncan Phillips

Diane Duncan Phillips

(above, left to right) Billy Lee Riley, Jerry Phillips, John Prine, Knox Phillips

Indeed, Prine, who passed away last week from complications related to COVID-19, redefined his career more than once in Memphis, especially in the latter example, when recording Pink Cadillac at Phillips Recording Studio. Hearing stories of its making from Jerry Phillips, who co-produced the record with brother Knox (with an assist from paterfamilias Sam), sheds some light on just how much Memphis resonated with the songwriter. The album, an eclectic mix of rock-and-roll, funk, and country styles, with only half the tracks being originals, decisively stamped Prine’s identity as something more than your typical troubadour. I spoke with Phillips recently about all the juicy details.

Memphis Flyer: By 1979, John Prine was well established as a folk-centric songwriter. He was expected to play an acoustic guitar with a lot of finger picking. So Pink Cadillac must have thrown the industry for a loop.

Jerry Phillips: Yeah, it did. John wanted to do something different, and he picked the right people because the Phillips family has never followed the beaten path on anything. We weren’t just going to cut another folk album. Those are great, don’t get me wrong, but to cut another folksy John Prine album like all the rest of ’em would have been of no interest to any of us.

You know, I don’t think John had ever cut an album with his own band. So that’s what he wanted to do. We rented him an apartment, fully furnished, and he stayed in Memphis for three months, him and his whole band. It was crazy. We cut 30 songs on that session. We were supposed to cut 12! And we had everybody from the Everly Brothers to Billy Lee Riley dropping by the studio. There were some other things going on, too, we don’t want to talk about …

MF: I’ve read there were 500 hours of tape cut at that time.What happened with all the extra stuff that didn’t make it to the album? Has any of it come out?

JP: Well, we have it in storage. Knox kept the tape machines running, basically, the whole time the session was going on. And a lot of that stuff, he re-cut. The next album was Storm Windows, and we had already cut that song, “Storm Windows,” in our sessions. But yeah, we’ve got lots of 16 track on John Prine.

MF: The record has proven its longevity. It’s more respected now than reviews at the time would suggest.

JP: Rolling Stone panned that album bad. They said it was the worst John Prine album ever. And The New York Times review [by Robert Palmer] said it was one of his best. So that made all of us feel kinda good. We had defied the corporate mentality in making that record, and the fact that the record company basically hated it [laughs], we thought that was great.

But we weren’t trying to be insane. We were trying to cut a good record. Just one that went off in a different direction. John loved Sam. He would talk about the evangelical fervor he had in the studio. And we can’t leave out my brother Knox, who has his own wild way of producing. Sam only came in for a couple of days. Knox called Sam and said, “You’ve got to come in. This guy sings so bad, you’re gonna love him.” And he didn’t mean he sang off key, but that he sang so different. Like every one of Sam’s artists.

John Prine was no chicken shit, but on “Saigon” and that stuff, we had to really pull it out of him. Sam would say, “Put some sex into it! Slow it down and put some damn sex into it!” Because he was in a different genre than what he was used to. But he pulled it off. I don’t think there was ever a record like that before or since!

John came by the studio last year, and we sat in the mastering room with Jeff Powell while he cut John a brand-new, fresh vinyl master 45 of “Saigon” and “How Lucky,” the two songs Sam recorded on him back then. Both of us had tears in our eyes, listening to that stuff. Because it was a pivotal part of his life, and mine, too.