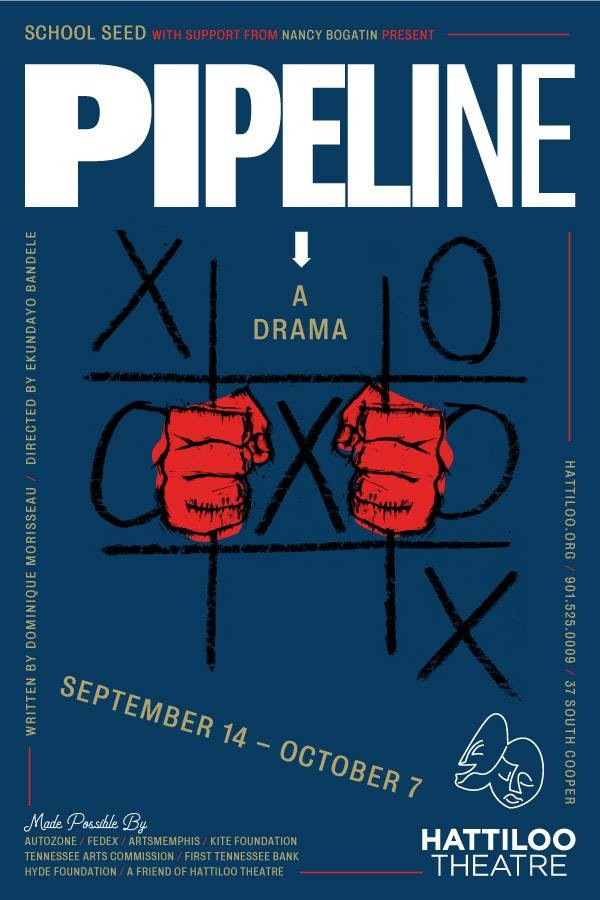

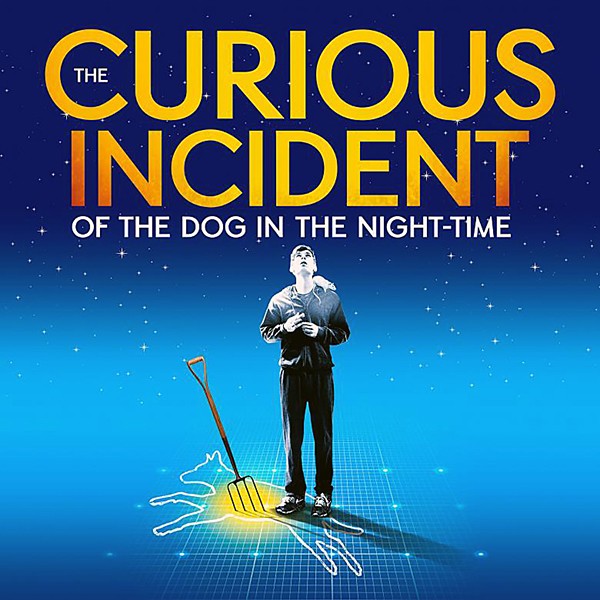

A thread of formalism connects all of the dramas currently on stage in Memphis. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time at Playhouse on the Square is a surreal treat adapted to the stage by British playwright, Simon Stephens who also wrote Heisenberg, currently on stage at Theatre Memphis. Even Pipeline, Hattiloo’s exploration of the school-to-prison dynamic is both hyper-real and coldly academic.

The narrator’s never described as “autistic,” but the tropes are familiar. Curious Incident‘s young detective is brilliant at math but not so good with figurative speech or human contact, and he struggles with sensory overload. The play uses dream logic augmented by strobe lights and noisy, confused babble to communicate the 15-year-old’s physical discomfort. It’s a highly effective exercise in irony and diminishing returns. Nobody suffering from sensory issues could ever withstand such a barrage.

Christopher finds a neighbor’s dog stabbed with a pitchfork. Following the example of Sherlock Holmes, he aims to solve the mystery, even if he has to run away from home in search of his dead mother to do it.

Inventive and gorgeous, Curious Incident is theater unfolding just at the edge of dance. It’s a hero’s journey, and, as Christopher, Ryan Duda makes for as brave and sympathetic a hero as anyone could hope for.

Through October 7th, Playhouse on the Square

Heisenberg isn’t about the famously conflicted WWII physicist tasked with developing nuclear weapons for the Nazis. His name’s never mentioned, but the metaphor at the heart of Theatre Memphis’ sturdily built production looms large: Who can predict the places we’ll go before life’s curtain comes down? It’s a suspenseful romance following Alex Priest, a reserved, 75-year-old Irish-born butcher living in London, whose life is upended by an American woman with ulterior motives.

Alex is shocked when Georgie sneaks up on him at a train station and kisses him on the back of the neck. She claims mistaken identity, but sticks around anyway, launching an awkward, one-sided conversation. Thus begins a complicated relationship between the mouthy 42-year-old and a quiet but soulful septuagenarian.

Georgie’s a “manic pixie dream girl” out of central casting, but aged to middle years. Unlike the cinema archetype, however, Georgie’s been doing her quirky carpe diem shtick long enough to have a backstory. With impure intentions she storms into Alex’s life like a 42-year-old Kirsten Dunst, drawing him into an unexpected adventure through the sheer force of her quirk. Sexual awakenings and second chances follow.

As Georgie, Natalie Jones comes on like a weird tornado. Jerry Chipman’s Alex blushes and giggles his way through the awkward stuff in a sweet, complete performance that’s maybe a little too passive for a little too long.

Through October 7th, Theatre Memphis

Inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry and Richard Wright’s prose, Dominique Morisseau’s Pipeline is a teaching play where the “school to prison” paradigm is deconstructed and reassembled in a series of broad strokes and emotionally fought conflicts. Hattiloo’s unusually wooden production is only sporadically successful in giving Morisseau’s brief, panic-attack of a show the life, the urgency, and inevitability it needs to cook.

Pipeline opens with Laurie, a public school teacher self-identifying as a “white chick who’s never had the luxury of winning over a class full of black and Latino kids.” She describes her teaching gig as “war.” Kids are the enemy, and she’s got a knife scar to prove it.

Nya, Laurie’s African-American colleague shows grace in the face of so much white noise. Her son Omari faces expulsion from a private school after pushing his teacher. When Nya’s ex-husband, a brusque and evidently successful man of business becomes involved, things get class-and-gender conscious real quick.

Through October 7th, Hattiloo