It’s no secret that vinyl is resurgent. After being eclipsed first by CDs in the 1990s and then by streamed digital music, records were nigh impossible to find in mainstream stores for many years, until around 2008, when the manufacture and sales of vinyl albums and singles began to grow again. Since then, the trend has only accelerated, with market analyses predicting continued annual growth between 8 percent-15 percent for vinyl musical products over the next five to six years.

What fewer people realize is how every step of the process that makes records possible can be found in Memphis. “The Memphis Sound … where everything is everything,” ran the old Stax Records ad copy, and that’s especially true in the vinyl domain: All the elements are within reach. Johnny Phillips, co-owner of local record distributor Select-O-Hits, says “There’s not very many cities that can offer everything we offer right here. From recording to distribution, from inception to the very end. Everything you need, you have right here. Memphis is like a one-stop shop for vinyl right now.”

From the musicians themselves to the final product you take home on Record Store Day, here are the 10 pillars upon which our Kingdom of Vinyl rests, 10 domains which thrive in Memphis as in no other city.

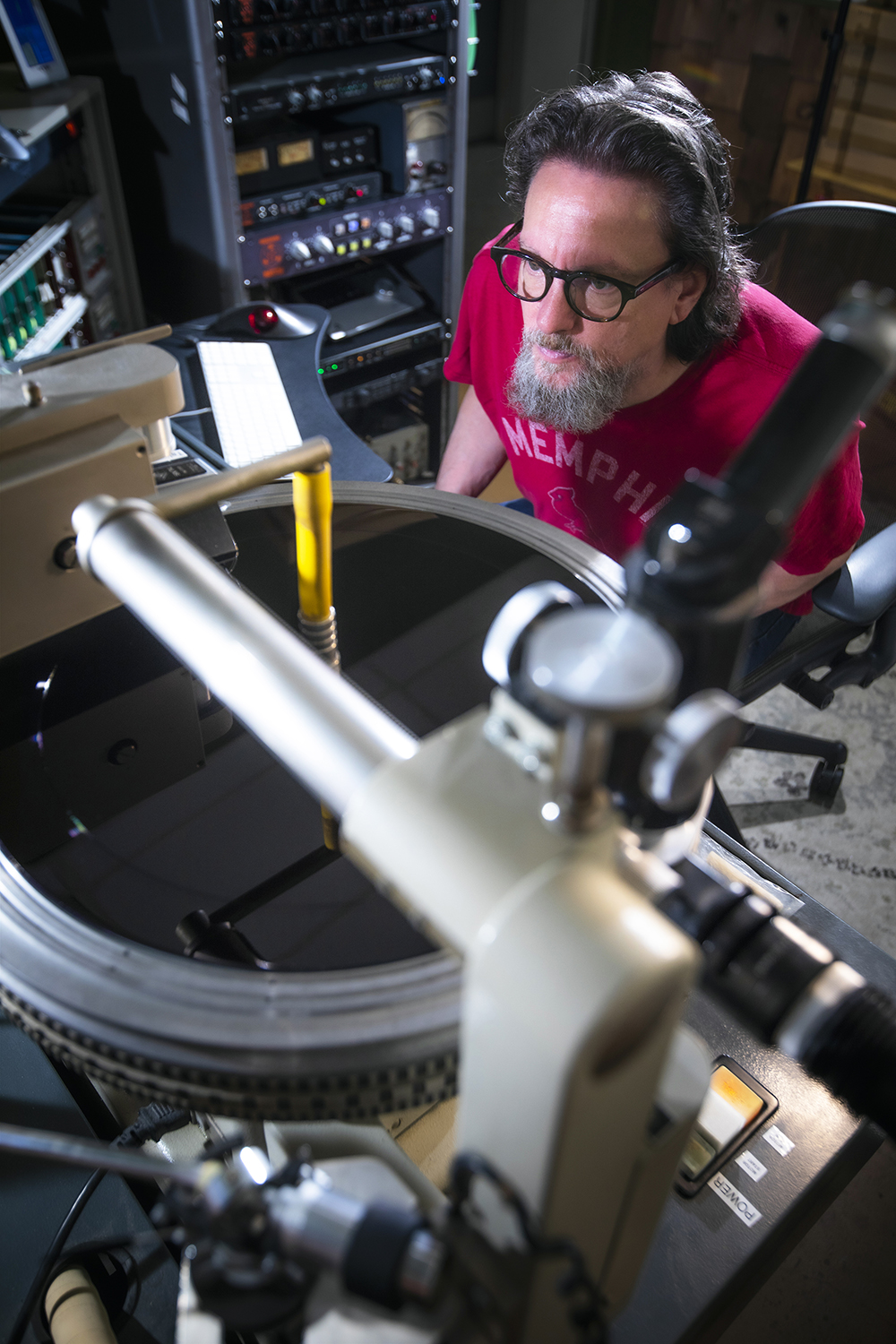

Mastering

A lacquer master, freshly cut on a lathe, offers a level of high fidelity that most listeners, even record aficionados, almost never hear. But Take Out Vinyl, run by Jeff Powell and Lucas Peterson from a room in Sam Phillips Recording, is that rare beast, a vinyl mastering lab, where raw audio from tape or a computer is first transferred to plastic and one can sometimes hear a lacquer playback. It’s not meant to be listened to. The discs cut here would typically be used to create the metal discs that stamp the grooves onto the records we buy, but the lacquer itself is too soft for repeated plays. And yet, for those who’ve heard a playback from a freshly cut lacquer, the quality is haunting.

That was the idea behind the one-off Bob Dylan record auctioned at Christie’s last month for $1.78 million. Spearheaded by producer T Bone Burnett, a new recording of Dylan performing “Blowin’ in the Wind” was cut onto a single lacquer disc, never to be duplicated or mass-produced.

To help make it a reality, Burnett enlisted Powell, one of the world’s most respected mastering engineers. “Lacquers are very soft,” says Powell. “We can’t play these things after I cut them or it destroys the groove. You lose a little high-end every time you play it. T Bone’s idea was to try to capture that sound of a fresh cut lacquer, but one that you could play over and over again, even up to a thousand times, with no degradation to the sound. And that’s what we have accomplished.”

The trick was finding a way to protectively coat the lacquer after it had been cut, and after years of R&D, the labs enlisted by Burnett found the right compound. “T Bone says the coating is only 90 atoms thick,” says Powell. “A human hair is about 300,000 atoms thick — that’s how thin the coating is. It was derived from a protective material used on satellites.”

Ultimately, says Powell, the goal was to reassert the value of vinyl records over digital media. “The purpose of this was not to see how much money could be made,” says Powell, “but to show how music has been devalued to next to nothing. T Bone wanted to establish that a recording like this should be considered fine art.”

Manufacturing

The notion of a vinyl record as fine art is not so alien to legions of collectors who curate their own personal galleries of albums and singles. But even the rarest of records were mass-produced at one time, and Memphis has that department covered as well. For decades, nearly all of the records recorded in Memphis were made at Plastic Products on Chelsea Avenue. Such was the pressing plant’s impact that an historical plaque now marks where it once stood. But in recent years, a new business has taken up the torch of vinyl manufacturing.

In 2015, the Memphis Flyer alerted readers to the fledgling Memphis Record Pressing (MRP), which arose from a partnership between Brandon Seavers and Mark Yoshida, whose AudioGraphic Masterworks specialized in CD and DVD production, and Fat Possum Records, whose co-owner Bruce Watson first suggested that they move into vinyl production. Now, it’s in the hands of Seavers and Yoshida and GZ Media, the largest vinyl record manufacturer in the world, and the Memphis company is expanding dramatically.

As Seavers points out, the world of vinyl has evolved as well. “When we started, we searched the world for record presses, which was really a challenge. Back in 2014, there were no new machines being built. You had to scour the corners of the earth to find ancient machinery and bring it back to life. Fast-forward to 2018, when a few companies emerged around the world that invested in building new machines. We started bringing in these brand-new, computer-controlled machines that were very different from our old machines. And that started the process of expansion. Through 2018-2021, we replaced our aging equipment bit by bit, and in September of last year, we replaced the last of our old machines.”

The pandemic was actually a boon to the young company. “We reopened in May of 2020, and by June our orders had skyrocketed. We were overwhelmed. And by the first five weeks of 2021, we booked three-and-a-half months’ worth of work in five weeks. So to say it overwhelmed us is an understatement. Now we’re sitting on a quarter-million units’ worth of open orders. So, it’s insane to see the demand grow. Before Covid, we had reduced our lead time to eight weeks. Now, it’s frustrating to quote nine months of lead time to new customers because that amount of time is life and death three times over for some artists. That’s why we’re so intent on expanding as quickly as possible.” Construction of additional facilities, expected to be operational in October, is now underway.

Distribution

Once the records are made, where do they go? Thanks to the decades-old Select-O-Hits, the answer is “across the globe.” Johnny Phillips reckons it’s the oldest distribution service in the world, and it may be one of the oldest businesses in Memphis, period. “In 1960, my dad, Tom Phillips, was Jerry Lee Lewis’ road manager. When Jerry Lee married his 13-year-old cousin, he couldn’t be booked anywhere. My daddy put all of his money into promoting Jerry Lee, and he lost it all. So, he came up from Mobile, Alabama, to Memphis and went to work with my uncle Sam, taking back unsold returns: 45s, 78s, and a few albums. We gradually grew into one of the largest one-stops in the South, supplying all labels to smaller retail stores. There used to be over 25 retail stores in Memphis, believe it or not. And then in the early ’70s, we started distributing nationwide. My dad retired, and my brother Sam and I bought him out.”

Over the years, Select-O-Hits has seen every ebb and flow of the vinyl market, including a major uptick after the advent of hip-hop. “We were the first distributor for Rapper’s Delight by The Sugar Hill Gang in 1979,” notes Phillips. That tradition continues today. “We’ve released about half of Three 6 Mafia’s catalog that we control in the last two years, on colored vinyl. And we distribute it all over the world.” And if the distribution numbers are not what they used to be before CDs and then streaming took over, they are climbing steadily. “Back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, we were selling half a million vinyl records. But now we’re doing 5,000, 15,000. Still, last year was our biggest vinyl year ever [since CDs became dominant], and this year is looking just as good.”

Record Stores and Record Labels

If Select-O-Hits is moving the product around the world, it needs to land somewhere, and in Memphis that means record stores. Though we no longer have 25 retail outlets for vinyl, there are several places to buy records here. The granddaddy of them all is Shangri-La Records, founded by Sherman Willmott in 1988, then taken over in 1999 by Jared McStay, who now co-owns the shop with John Miller.

“The first couple of years,” says McStay, “I had to bet on vinyl because I couldn’t compete with the CD stores, like Best Buy or whatever. I was getting crushed, until I realized I could never compete with them. In the early 2000s, they were phasing out vinyl, and even stereo manufacturers stopped putting phono jacks on their stereos. But I had tons of records.”

Around the same time, Eric Friedl was running a small indie label, Goner, which ultimately became the Goner Records shop when Zac Ives joined forces with Friedl in 2004. They too leaned into vinyl from the very start. “I think Eric had done maybe two CDs at most when we joined forces and started expanding the label in 2004,” says Ives. “Out of his 10 or 11 releases, I think only The Reatards had a CD release. The rest were only on vinyl. There was no giant resurgence of vinyl for us. Those things came up around our industry, but we never left that model. And that’s how it was for most smaller, independent labels, especially in punk and underground realms.”

Combining a record shop with a record label is a time-honored tradition in Memphis, going back to Stax’s Satellite Records, and it carries on today through Shangri-La and Goner, which have both been named among the country’s best record stores by Rolling Stone. Both stores’ dedication to vinyl relates to their investment in live bands. Gonerfest, which brings bands, DJs, and record-shoppers from around the world, will be enjoying its 19th year next month, and Shangri-La has hosted miniature versions of that for years.

“We’re having Sweatfest on August 13th,” says McStay, “and we haven’t had one in three years because of the pandemic. There are going to be thousands of bargain records. We’ve been hoarding them for three years!” Meanwhile, local bands will perform in the parking lot, a pre-Covid mainstay of Shangri-La for most of its existence.

Though Goner boasts its own label, and Shangri-La has spawned at least three (Shangri-La Projects, plus the loosely affiliated Misspent Records and Blast Habit Records), not all stores do so. River City Records opened last year and, along with Memphis Music and A. Schwab, is already doing a brisk vinyl business in the Downtown area. Meanwhile, the city has several vinyl-friendly labels untethered to any retail outlet, namely Back to the Light, Big Legal Mess/Bible & Tire, Black and Wyatt, Madjack, and Peabody Records. These local imprints and the bands they sign, in turn, feed into the doggedly local support that the above mastering, manufacturing, and distribution businesses offer. As Powell says, “Anybody local, I’ll always try to move heaven and earth to get them ahead of the line a little bit and treat them special. Because you know, it’s Memphis, man!”

Archives, Audio Technology, Community Radio, and DJs

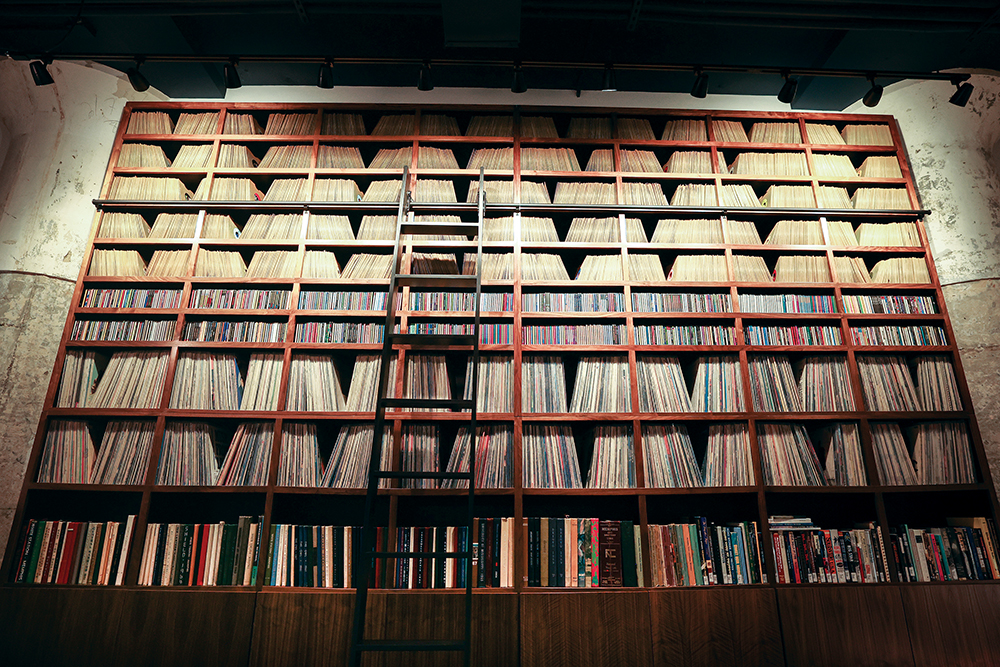

A wide swath of this town’s music lovers are brazenly vinyl-centric, and that demographic has a ripple effect in other domains. The Stax Museum of American Soul Music, for example, boasts the huge archive of Bob Abrahamian, a DJ at the University of Chicago in the 1990s, with more than 35,000 singles and LPs, now being cataloged by a full-time archivist, Stax collections manager Leila Hamdan.

Then there’s the Memphis Listening Lab (MLL), founded last year on the strength of the music collection of John King, a collector’s collector if there ever was one. As a promoter, program director, and studio owner, he’s collected music all his life. Now, his roughly 30,000 45s, 12,000 LPs, 20,000 CDs, and 1,000 music books reside in the public archive of the MLL, free for the listening and even free to record. Further, MLL has hosted countless public events where classic or obscure albums are played and discussed in depth.

The listening lab also benefits from a less-recognized aspect of vinyl culture in Memphis: the technology. Being outfitted with high-end, locally made EgglestonWorks speakers enhances the listening experience at MLL considerably. And the city is also home to George Merrill’s GEM Dandy Products Inc., which markets his highly respected audiophile-grade turntables (one of which MLL hopes to acquire).

Another archive boasting EgglestonWorks speakers is the Eight & Sand bar in The Central Station Hotel. The private bar was envisioned as a place to celebrate Memphis music history, and its dual turntables are duly backed by a huge vinyl library of mostly local music. “Chad Weekley, the music curator, is doing an incredible job there,” says Ives. The bar now plays host to the DJs who enliven Gonerfest’s opening ceremonies, and the hotel has even offered package deals combining room reservations with gift certificates to the Goner shop.

And let’s face it, this town is crawling with great DJs. In a sense, they are the ultimate vinyl record consumers, and thus help to drive all the other institutions. “It’s similar to a band,” says Ives, “because you’re taking your knowledge of music and putting it back out into the world in some way. I love hearing somebody’s personality coming through their radio program or DJ event. … Sometimes at venues like Eight & Sand, sometimes on community radio.”

The latter is clearly fertile ground for those who favor the sound of vinyl. Both WEVL and WYXR sport turntables in their on-air studio rooms, not to mention their own vinyl libraries. As WYXR program manager Jared Boyd says, “I’m a record collector myself, and for a time I was DJ-ing at Eight & Sand and using those turntables. So, when we started the radio station, we wanted people to be able to have that experience without having to go down to Central Station. We wanted these people who collect deeply to broadcast these really unique finds. I particularly wanted to cater to people who use records.”

The Music

And so we come full circle, following vinyl’s great chain of existence back to the reason we all want it in the first place: music. And it’s undeniable that the music this city produces fits our predilection for vinyl — from Jerry Lee Lewis’ piano swipes to the guitar/organ growl of “Green Onions,” from the choogling riffs of power pop to the crunching, distorted damage of punk, the sounds of this city lend themselves to the weight and warmth of music’s greatest medium. Just drop a needle on your favorite band and you’ll hear the truth in Brandon Seavers’ words: “Memphis is the grit to Nashville’s glitz,” he says. “And grit sounds a lot better on vinyl.”