Most Memphians probably won’t recognize the name cut into the wall over the door leading to the new Hattiloo Theatre’s smaller black box theater. It’s not one of the corporate donors or lifetime philanthropists whose names tend to appear in such places. Katori Hall is a 33-year-old Craigmont High graduate and an internationally acclaimed playwright, whose provocative work is often set in parts of Memphis that most local theatergoers have only seen at a distance, if at all.

It was a steamy afternoon in June 2010, when I first met Katori Hall at the Little Pie Shop in Hell’s Kitchen. Memphis had invaded New York that summer. Broadway was buzzing with news about Joe DiPietro and David Bryan’s Memphis, which had won the Tony for best new musical only a week before. Around the corner, at the Nederlander Theater, Million Dollar Quartet introduced audiences to Sun Studio founder Sam Phillips, who shared his spotlight with Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley. Off Broadway, in Manhattan’s Garment District, Sister Myotis’ Bible Camp, a Steve Swift/Voices of the South creation, enjoyed full and appreciative houses at the Abingdon Theatre. And there I was in the middle of it all, having pie with Hall, who didn’t have a play in New York at the moment but was keeping busy. Her play The Mountaintop had just won London’s Olivier Award for best new work, and Hall was gearing up for its 2011 Broadway launch, with Samuel Jackson and Angela Bassett in leading roles.

“When I was growing up, I didn’t think I would be a playwright,” Hall said, listing school trips to see regional staples like Ballet Memphis’ The Nutcracker and Circuit Playhouse’s production of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe among her few brushes with live performance outside of church.

“The unfortunate thing about Memphis is that there wasn’t a lot of new theater being done,” Hall continued. “Most regional theaters need a stamp of approval to say that a play is good, even if the play has nothing to do with that community’s experience.” Hall said she’d love to bring new plays home to workshop, but she didn’t know where she could take them.

When I asked if she knew about the Hattiloo Theatre and its ambitious founding director, Ekundayo Bandele, Hall twisted her face into a mask of skepticism.

“That guy’s not from Memphis. He’s from Brooklyn,” she said, not so much dismissing Bandele as she was dismissing the idea that any New York poser had half a chance in her hometown.

That was then.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

of the Hattiloo Theatre

In the years since, Bandele’s Hattiloo Theatre has produced The Mountaintop, in conjunction with Circuit Playhouse, and resurrected an infamous Memphis housing project for the landmark production of Hall’s ensemble drama, Hurt Village. When Bandele’s new 10,000-square-foot facility opens its doors in Overton Square later this month, the young playwright’s name will be there, just spitting distance from Circuit Playhouse, where Hall once handed out programs in order to see A Tuna Christmas for free.

“She’s giving back,” says Bandele, thrilled to have Hall participating in such a meaningful way.

Over the years, the Hattiloo’s founding executive director, who grew up splitting time between Brooklyn and North Memphis, has insisted that he doesn’t only want to produce plays that have a preexisting stamp of approval. He doesn’t want the next August Wilson or Lorraine Hansberry to fall between the cracks, and he doesn’t want another Katori Hall to graduate high school in Memphis having only been exposed to A Tuna Christmas and other plays that have nothing to do with her experience.

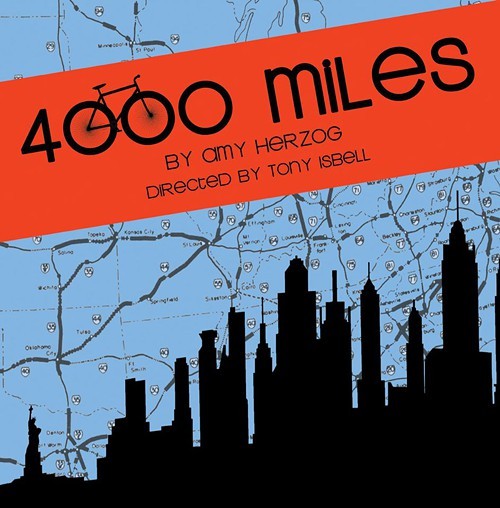

“She is making some serious waves in the theater world, and she’s going to be a writer in residence,” Bandele says of Hall. “In 2015, we’re going to do a play called Saturday Night/Sunday Morning.”

Bandele describes that production as a world premiere, although an earlier version of the show was produced in Chicago.

Set in a Memphis beauty parlor, Saturday Night/Sunday Morning is a period drama telling the story of a group of young African-American women during the last days of WWII.

Bandele has always wanted emerging work to be a strong part of the Hattiloo’s mix alongside classics of the African-American canon and popular favorites such as Once on This Island, the calypso-inspired musical chosen to open the new theater. To that end, the theater has rolled out a rotating playwright in residence program, with a $6,000 stipend for the chosen artist.

“Imagine coming to a place where you see shows about Memphis,” Bandele says, ticking off possible subjects that include Tom Lee, the hero of the M.E. Norman disaster, and Robert Church, the city’s first black millionaire.

“In the past, we were dedicated to development,” he says. “We didn’t have many black actors, directors, or designers when I started this, so we found some and we developed them. Now that we’ve got some, I think we have to be dedicated to excellence.”

“Conservative” and “modern” are the words Bandele uses to describe his new theater, with its open, fluid, public spaces, designed by Memphis’ Archimania architecture firm. The walls will feature important African-American theater artists in portraits created by local African-American artists.

To give visitors a sense of how much larger the new Hattiloo facility is, Bandele has developed a nifty trick. He gives detailed virtual tours of the old Marshall Avenue location without leaving the new facility’s black box theater.

“We’d be walking past the bar now,” he says, running his fingers along the invisible curves of an imaginary counter. He walks past the “box office window,” drawing it in the air, before pointing to where the men’s room would be.

“You could fit the entire [former] Hattiloo into just this one space,” Bandele marvels. But the increased size doesn’t mean decreased intimacy. The larger space seats 150 people and is never more than four rows deep when configured for a thrust stage, as it will be for the opening musical, Once on This Island. It’s only nine rows deep when configured for a standard proscenium, as it will be for the second show, Stick Fly.

The old theater was noted for bringing spectators close to the action, but it seated half as many people, was fairly inflexible, and 11 rows deep, counting the balcony.

The new space offers a cozy green room for performers to use and multiple dressing rooms. “That means we can do shows with up to 22 performers easily, without having actors piled on top of each other,” Bandele says. “We’ve got enough room to run two shows at a time.” He plans to eventually do just that.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

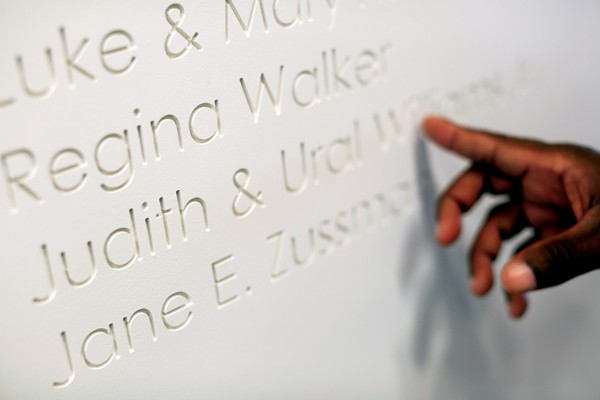

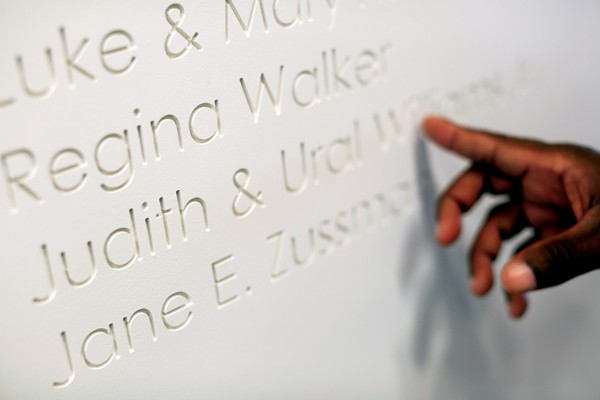

A portion of the new Hattiloo’s donor wall

Bandele’s regular players won’t be the only artists on hand at the Hattiloo’s public grand opening on June 28th. Memphis’ emerging bilingual theater troupe, Cazateatro, is scheduled to perform, as are Ballet Memphis and Opera Memphis, two area institutions the Hattiloo has worked with in the past. Bandele says he hopes to forge similar community partnerships with other organizations, including the Indie Memphis Film Festival, which will also have representatives in attendance to screen short films and offer a brief sample of things to come.

“Indie Memphis will show films at the Hattiloo during their festival this year,” Bandele says. The deal was struck with one request: All films screened at the new venue will be related in some way to people and communities of color. It’s a challenge that excites Indie Memphis executive director Erik Jambor.

“Adding the Hattiloo makes our festival more festive,” Jambor says, delighted to have so many screens within a three-block pedestrian-friendly radius. In recent years, Indie Memphis has screened films at Playhouse on the Square, Circuit Playhouse, and Studio on the Square. Hattiloo will be the growing festival’s fourth location, and Jambor says he hopes the organizations can both benefit by introducing their audiences to one another.

“I keep saying, it’s like the Neshoba experiment,” Bandele says, comparing Overton Square’s future to a 19th-century commune near present-day Germantown. It’s a difficult analogy, considering that Neshoba was founded as a means for slaves to earn their emancipation through labor while preparing for the colonization of Liberia and Haiti.

Acknowledging that except for Beale Street and FedExForum, Memphis remains mostly culturally segregated, Bandele speaks more to Neshoba’s never-achieved goal of becoming an interracial, egalitarian utopia. It’s an idea he’s been floating in some form or another since he first announced in 2010 that the Hattiloo would be moving to Midtown.

At that time, in a short but memorable address at Playhouse on the Square, Bandele asked everyone to try and imagine a new kind of entertainment district, one with a sparkling new parking garage where crowded elevators buzzed with the mingled conversations of black and white theatergoers on their way to grab a pre-show bite to eat.

“That’s the Memphis we all want to see,” he said.

Tony Horne, the director and educator who co-founded the Memphis Black Repertory Theatre at TheatreWorks, describes Bandele as a “strong visionary” who doesn’t see obstacles. “He just doesn’t,” Horne says. “Ekundayo sees possibilities. That’s who he is.”

Horne describes the Hattiloo’s new home in Overton Square as the culmination of a slow but steady movement that begins with efforts like the Beale Street Repertory Company, Blues City Cultural Center, Erma Clanton’s Evening of Soul performances, and his own work in Overton Square with the Black Rep.

“We’ve always had tremendous talent and leadership,” Horne says. “But there’s something about Ekundayo and the timing of where we are in the history of this city. Because of all these early efforts, there was this thing that was ready to come to the fore. But it was Ekundayo’s time to take that energy and grow it — to really make it into something.”

Horne’s multi-award-winning staging of The Color Purple at Playhouse on the Square featured numerous performers who cut their teeth at the Hattiloo. He was an obvious choice to helm Once on This Island, which opens July 18th.

Horne, who also directed The Wiz at Hattiloo, thinks the theater has done a good job with its musicals in the past but can’t wait for audiences to see what a difference the new space will make. “We’re gonna show off a little bit,” he says.

“Once on This Island isn’t a regional premiere, but that’s okay because it’s so beloved,” Horne says. “It’s a fairy tale about the enduring power of love with a lot of color and music. It’s really going to showcase the new space and all the talent we have here.”

Meet Hatti and Loo

Ekundayo Bandele stands at the entrance of his new Overton Square theater and stares up at the name on the wall: Hattiloo. “This is probably what I look at the most,” he says, as work crews prepare to lay the lobby carpet and install sprung floors in the venue’s two black box theaters.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

of the Hattiloo Theatre

“Theatre Memphis and Playhouse on the Square are named for where they’re located,” Bandele says proudly, reflecting on his decision to name the theater after his daughters Hatshepsut (Hatti), a visual artist, and Oluremi (Loo), who was born with cerebral palsy, loves musicals, and works at the Hattiloo with her dad.

But what do Hatshepsut and Oluremi Bandele think about lending their names to such a big project?

Memphis Flyer: So who are Hatti and Loo?

Hatshepsut: I see myself as a visual artist. It started my junior year in high school. I was drawn to mixed media and had a serious relationship with it until my dad introduced me to photography. I took a course in it at the U of M and was stubborn, thinking I wasn’t going to like it. But I fell in love. I like portraits. Usually I focus on African-American culture, combined with African culture like face painting. I want more than a pretty picture.

Oluremi: I work at the Hattiloo. I like to help people. That’s just me. I like to go out with my friends and eat. I like camp. I like the musicals. Dad did Annie for me because it’s my favorite. And I like Crowns, the dancing and the music.

Are either of you actors? Or directors? Or playwrights?

Hatshepsut: I was in one play when I was 13, and I enjoyed it. But I get so nervous performing. So I tried it. But that’s not me.

Oluremi: My dad started me working [at Hattiloo] when I was 16 or so. He asked me if I’d like to work there and I said, “yes, sir.” Helping at Hattiloo makes me happy. It’s a part of my life.

Is it weird having this thing that’s named for you? Is it a responsibility?

Hatshepsut: I remember hearing my parents talking about it. I was young. We were at a lake visiting my parents’ friends. And I heard them say “Hattiloo.” It wasn’t a responsibility, it was just beautiful. But then going to the theater on Marshall and seeing the name on the building, it wasn’t just my sister and me. It was something that will always and forever grow. I remember in the beginning on Marshall it looked almost like a haunted house. You didn’t want to be there at night. We had those dinners and auctions to raise money to get the walls up. And you didn’t see the dust or that the walls hadn’t been built yet. You saw the passion and the unity it was creating in Memphis.

Oluremi: Me and my father, we’re like a team. We work together to make things happen. I tell him to write his grants. When it rains, I tell him to remember his hat. I don’t know where he’d be if he hadn’t hired me.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks