Vladimir Lenin supposedly said “There are decades when nothing happens, then there are weeks when decades happen.”

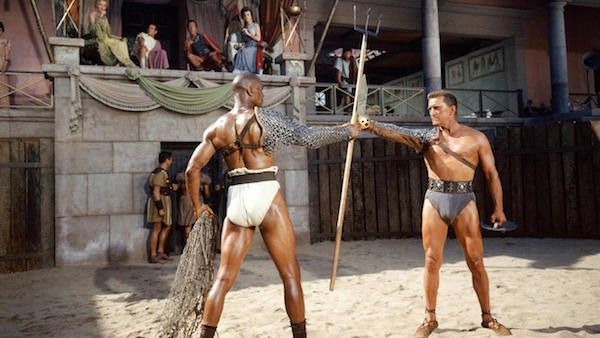

Although it was not evident at the time, the 1960 film Spartacus was at the center of one of those historical nexuses Lenin had in mind. The story began in 73 BC, when a group of 78 escaped Roman slaves led by a former gladiator named Spartacus gathered marauded through Italy. Eventually their movement grew into a force of about 120,000. After two years of rebellion, the Roman armies, led by eventual Triumvirate member Pompey, cornered the slave army in the toe of Italy’s boot and massacred them, crucifying at least 6,000 of Spartacus’ followers on the Appian Way.

The story of Spartacus’ rebellion, which became known as the Third Servile War (yes, there were multiple slave rebellions in Roman times), was overshadowed by events that followed, when some of the war’s major players were involved in the transformation of the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire. The defenders of Roman slavery became the biggest enemies of Roman democracy. But there was a subset of people who never forgot about Spartacus: Socialists. It seems natural that Karl Marx, the guy who told workers to rise up because “you have nothing to lose but your chains”, counted Spartacus as a personal hero. During World War I, when it became obvious that the German cause was lost, a Communist faction called the Spartacus League agitated to end the war and institute socialism in the country. But, just like its namesake, the Spartacus League was crushed after the war by the nascent Weimar government and its leaders executed.

The Communists had better luck in Russia, of course, and after allying with the Capitalist West in World War II, mutual suspicions and opportunistic politicians on both sides made America and the Soviet Union enemies in the Cold War. Hollywood, a supposed nest of Communist subversives, was one of the first targets of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). There were a lot of leftists in Hollywood, and some people, such as screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, had actually joined the Communist Party of the United States while Russia and the U.S. were still allies in the war. Trumbo was no subversive: He wrote the classic 1944 war film 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, and rightly considered publicly advocating for his political views as his Constitutional right, no matter how unpopular they may have been at the time. When Trumbo was called in front of HUAC in 1947, he refused to name any other writers, actors, or directors who had been members of the CPUSA. As a result, Trumbo was convicted of contempt of Congress, and, after losing an appeal to the Supreme Court on First Amendment grounds, sentenced to 11 months in prison. He was kicked out of the Writer’s Guild and became the most prominent member of the infamous Hollywood Blacklist, unable to work in the industry.

Trumbo’s story was dramatized last year, when he was played by Bryan Cranston on the big screen. Much of the running time of Trumbo is dedicated to the 1950s, when Trumbo ghostwrote dozens of films, including pulpy titles like From The Earth To The Moon and Oscar winners Roman Holiday and The Brave One.

The same year Trumbo was blacklisted, a young actor named Kirk Douglas made a splash playing next to Robert Mitchum in Out Of The Past. By the late 1950s, Kirk Douglas’ star was rising, and he wanted an iconic role to play after being passed over for the lead in Ben Hur. Douglas chose Spartacus, and brought on Trumbo in secret to adapt a biography of the revolutionary. Trumbo, a noted aficionado of amphetamines, cranked out the epic length screenplay in two weeks under the pseudonym Sam Jackson.

The historical epic proved expensive and logistically very difficult to pull off. After a week of production, Douglas, who was serving as exec producer, fired the director Anthony Mann and persuaded Stanley Kubrick to take his place. Kubrick at the time was an acclaimed b-movie director who had worked with Douglas on his anti-war film Paths Of Glory (which really should be the subject of a Politics and the Movies column on its own), and at $12 million, Spartacus would be the biggest project of his career. It was also the first time Kubrick had worked without total creative control, and to say he hated the process is a dramatic understatement. He famously sidelined the cinematographer Russell Metty, forbidding him to get near the camera. (Metty got the last laugh when his name was on the Oscar for Best Cinematography Spartacus won.)

When Douglas realized he had a hit on his hands, he publicly outed Dalton Trumbo as the screenwriter. The American Legion protested the film’s premiere, but when newly minted president John F. Kennedy crossed the picket lines, it effectively ended the Blacklist, and Trumbo worked openly in Hollywood until his death in the 1970s. Kubrick’s hard feelings didn’t stop when the film proved to be a huge hit and garnered acclaim as one of the best historical epics ever produced. He disavowed the picture and never worked with Douglas again.

Viewed today, the combination of Trumbo, Douglas, and Kubrick is fire. Game Of Thrones owes much of its formula of action, gore, sex, and politics to Spartacus. The screenplay is equal parts sword and sandals potboiler and thoughtful meditation on the nature of freedom. If you didn’t know the history of Spartacus as leftist icon, the politics are mostly confined to the distance between Roman opulence and the cruel lives of the slaves. Coming as it did on the eve of the Civil Rights movement, the subject of slavery held special resonance with American audiences.

As a director, I look at the huge battle scenes Kubrick staged with equal parts envy and horror. On the one hand, wow, who wouldn’t want to command a literal army of 20,000 Romans? On the other hand, they had to feed and clothe 20,000 people for what amounted to about five minutes of screen time.

Politics and the Movies 4: Spartacus (2)

But of course, the film’s most lasting legacy is in its final scenes, among the most iconic and deeply moving moments in American film history. The cry of “I’m Spartacus!” has been adapted by many movements, and parodied many times. But the scene has lost none of its power, and in context, coming after two hours of triumph and tragedy, it’s absolutely devastating. They just don’t make ‘em like Spartacus any more.

Politics and the Movies 4: Spartacus