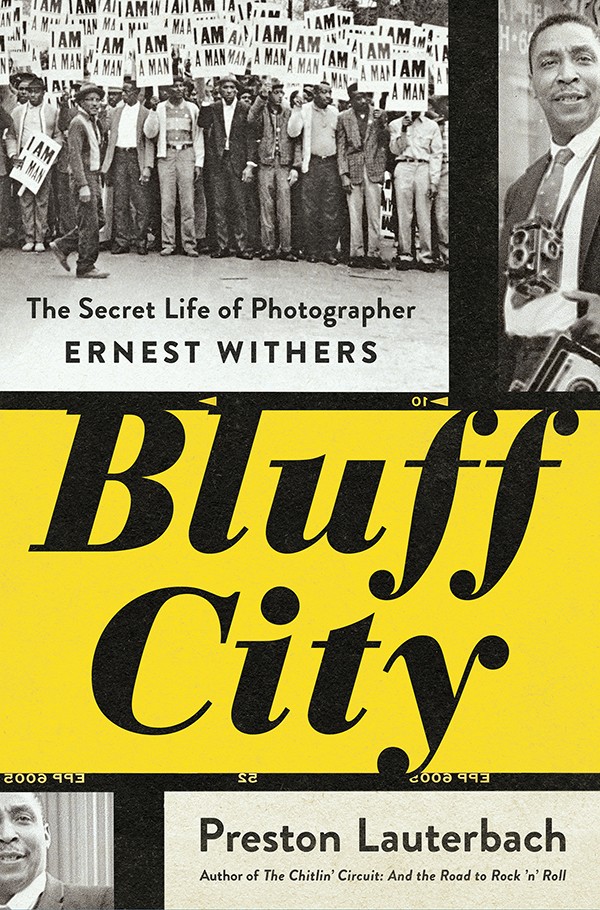

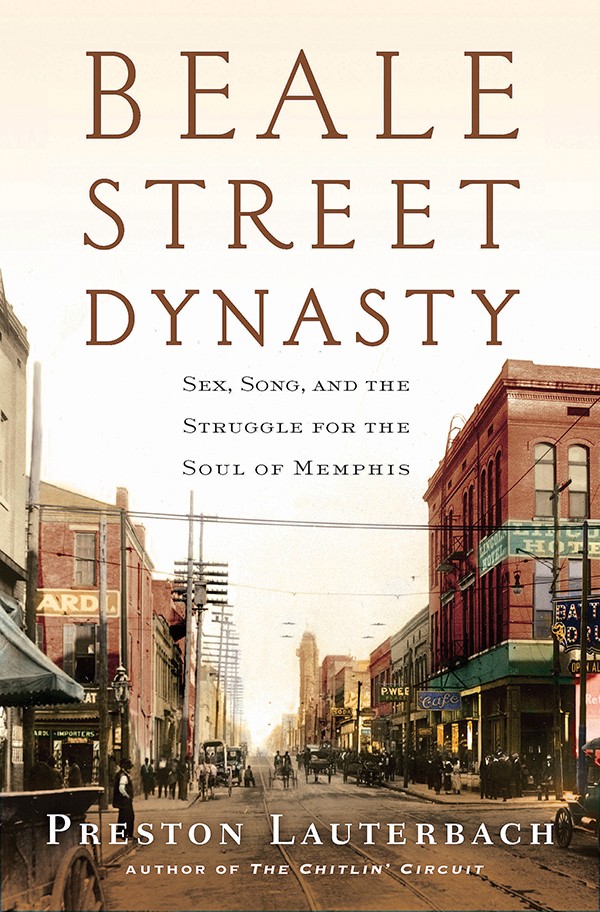

If there’s one thing Preston Lauterbach excels at, it’s creating an almost novelistic sense of place in which his thoroughly researched histories can play out. It’s something many noted about his ambitious surveys of Memphis in the 19th and 20th centuries, Beale Street Dynasty: Sex, Song, and the Struggle for the Soul of Memphis and Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers, which conjure up scenes of a city buzzing on every corner, before zooming in to the subjects at hand.

That also applies to his latest work, Before Elvis: The African American Musicians Who Made the King. True to its title, Lauterbach, who proclaims from the start that “Elvis Presley is the most important musician in American history,” delves into the stories of those geniuses of 20th-century Black culture who inspired Presley and made him what he was, offering a deep appreciation of their music and their lives as he does so. But he also evokes the sea in which they all swam, as waves of disparate cultures crashed on the bluffs of Memphis at the time.

“The city in the years between 1948, when the Presleys moved there from Tupelo, Mississippi, and 1954, when Elvis recorded his hit debut single,” Lauterbach writes, “was the type of furnace in which great people are forged, fundamentally American in its devastating hostility and uplifting creative energy. Elvis came of age in a revolutionary atmosphere.”

And yet Lauterbach’s first deep dive is, counterintuitively, into the Nashville scene of the ’40s and ’50s. The revolution in radio going on there may have been the Big Bang of rock-and-roll itself, and a hitherto unappreciated element of Presley’s exposure to African-American music in Tupelo, as the 50,000 watt signal of Nashville’s WLAC carried it “from middle Tennessee to the Caribbean and Canada.” When pioneering DJ Gene Nobles broke precedent and began playing African-American jazz, R&B, and blues, he “cracked the dam of conservative white American culture,” and that included Tupelo, a full two years before the Presleys moved to Memphis.

This, Lauterbach posits, was the most likely way a young Elvis would have heard Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right,” prior to making his own version a hit some years later. It had already been a hit for Crudup, who very likely did not play in Tupelo, as Presley later claimed. And from there, Lauterbach begins his fine-grained appreciation of Crudup’s life and career, including the ascent of “That’s All Right” up the charts in the ’40s, fueled in part by its spins on WLAC.

Zooming out for context, cutting to close-ups of Black artists’ lived experiences, and periodically panning over to how young Presley soaked it all in are what make this book a tour de force of both history and storytelling. A host of African-American innovators are celebrated along the way: Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton and her “Hound Dog,” Herman “Little Junior” Parker and his “Mystery Train.” But lesser knowns also receive their due. The influence of guitarist Calvin Newborn’s performance style, and brother Phineas Newborn Jr. along the way, is thoroughly explored, with Newborn’s anecdotes of Presley’s presence on both Beale Street and the family dinner table. And we read the tale of Rev. W. Herbert Brewster, the African-American minister at East Trigg Baptist Church, who not only composed classic gospel songs, but pioneered multiracial services in the Jim Crow era. One direct result of that was Presley’s regular attendance there. But Brewster’s story also reveals how mercenary the music publishing game was, as Mahalia Jackson and her accompanist Theodore Frye claimed at least one of Brewster’s compositions as their own.

Lauterbach does not shy away from the matters of song theft or cultural appropriation that continue to haunt Presley’s legacy. But he notes that Jackson’s usurpation of Brewster’s rights to his own song “was a theft as bold as anything Elvis Presley has been accused of and worse than anything Presley actually did.”

Tellingly, Lauterbach reminds us of the courage it took to blur color lines that seem so hard and fast to many Americans, and for many African Americans this was seen as a positive change. In the final pages, we return to Calvin Newborn’s assessment, who harbored no bitterness over his protégé’s success: “He was a soulful dude.”

Preston Lauterbach will discuss his new book with Robert Gordon at the Memphis Listening Lab on Friday, April 4th, 6 p.m.

Elise Lauterbach

Elise Lauterbach