Memphis music fans have strong opinions. Take the avid listener and Memphis Flyer reader who approached one of our writers while chilling near the Ferris Wheel at RiverBeat Music Festival last weekend. “I can’t believe it’s accepted to just play a backing track while an artist performs!” he said, noting that, as far as he could tell, that’s exactly what Busta Rhymes and Ludacris did during their sets. While it is indeed a common practice, especially with hip hop artists (but increasingly in other genres), did anyone else care? Given the enthusiasm with which those artists were greeted, it’s hard to claim that they did.

Take the ecstatic reception that Missy Elliot received for one of the best performances in the history of either Beale Street Music Festival or RiverBeat. Using only pre-recorded tracks, her Friday night headliner was a highlight of the weekend. While stage productions have become more elaborate in the “post-Beychella era,” too often that comes at the expense of the music. But Missy was firing on all cylinders — literally. After cartoon versions of Missy’s various phases introduced the show on the big screen, a car that looked like it was designed by Syd Mead appeared on the stage.

“Oh,” we all thought. “Missy’s going to drive around in the car.” No, reader. She WAS the car! The first of five costumes she wore in the course of the night was a Transformer-inspired drip which drew gasps from the assembled thousands. The rest of the evening was a parade of hits and bangers which drew heavily on Missy’s turn-of-the-century work with Timbaland. Surrounded by a crack cadre of dancers and MCs, she made a case for herself as one of the most important and influential artists of the last 30 years.

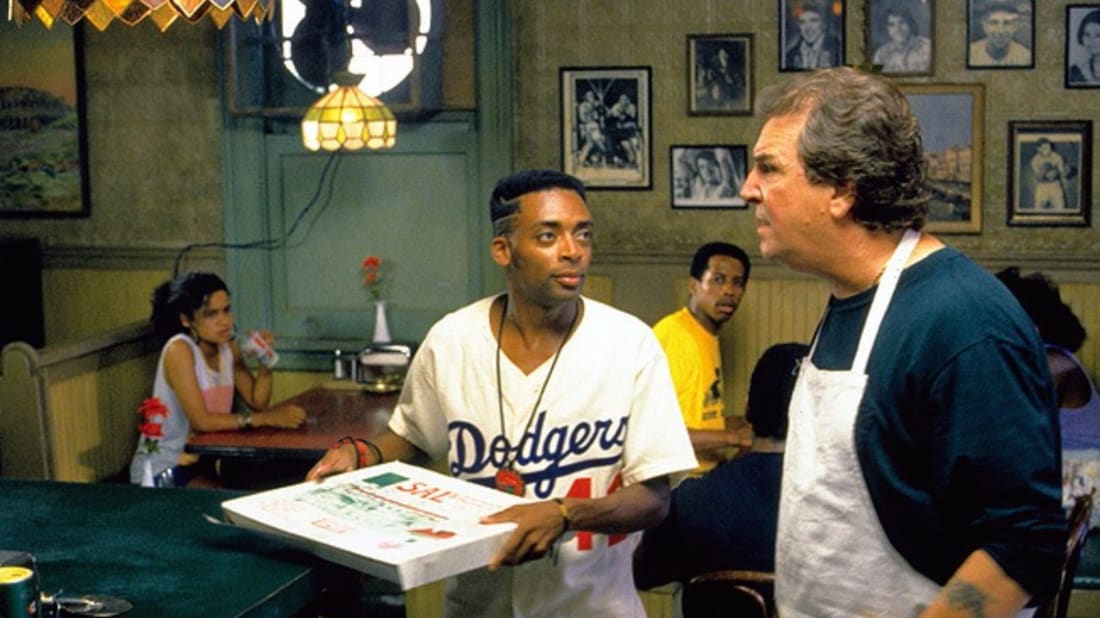

Yet most of the remaining standout performances of RiverBeat reveled in good old fashioned instrument-playing, such as Saturday’s set by The Hypos. This band, which includes Memphians Greg Cartwright and Krista Lynne Wroten, is a living tribute to making records in the traditional way, with a combo playing finely wrought songs in a room (and they’d been doing just that prior to their festival appearance, with Matt Ross-Spang), focused on the sound of the human voice, sans autotune. The pro sound system of the Bud Light Stage showed off all these strengths in their best light, including the group’s stellar harmonies.

Artist after artist took to the festival stages as if to prove that musicians playing instruments can still wow an audience. Anyone who saw the virtuosity of MonoNeon‘s set won’t forget his command of the bass Fender created in his name, droopy sock and all, complemented by a crack band and conjuring up a vibe close to George Clinton’s party-down approach, with an extra dollop of jazz in the mix. The bass virtuoso put on a low end clinic, taking the supporting instrument and shredding like a lead guitar. It was magical!

Local heroes FreeWorld also wowed ’em at Tito’s Pavilion stage, with their saxophonist’s home brew synth sax stealing the show (until his laptop crashed). They also arguably represented Memphis history more deeply than any other group, with front man Richard Cushing calling out the late Herman Green before they played one of Green’s compositions from his tenure with the group, “Earth Mother” — not to mention a sizzling version of “Green Onions” which benefited from the presence of a real Hammond organ in that stage’s backline.

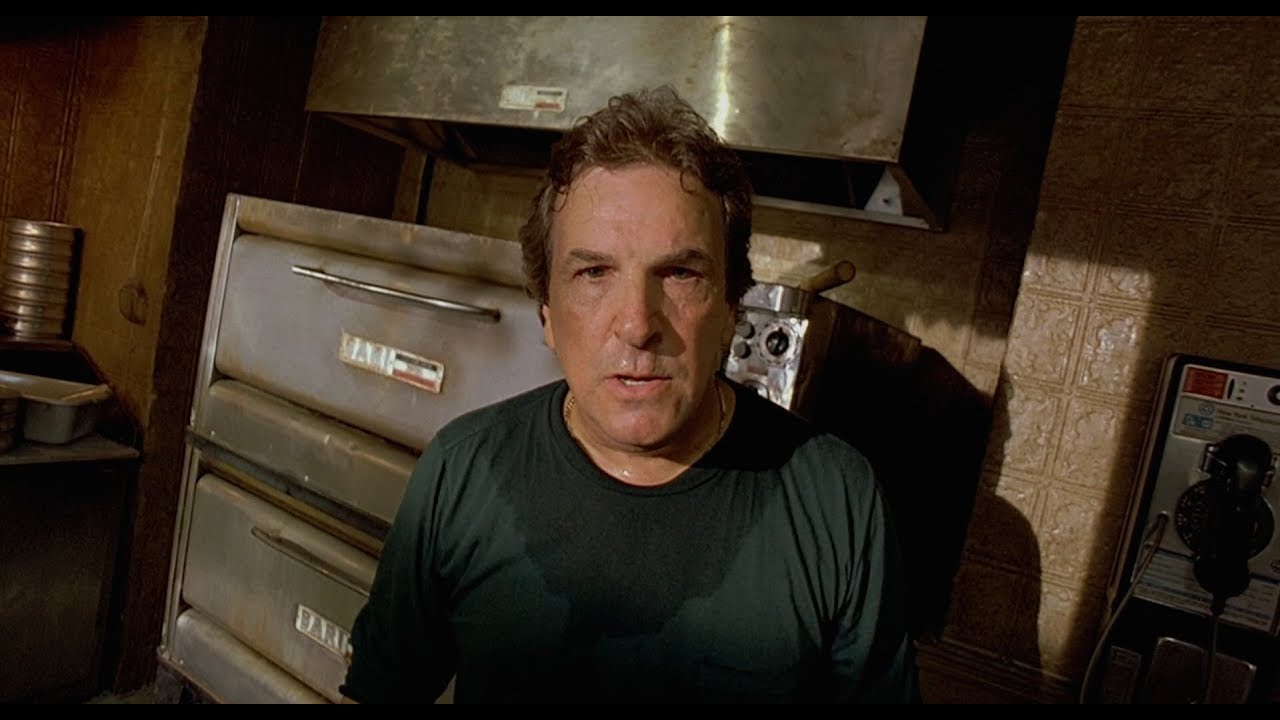

The Neckbones were a standout Oxford Mississippi band from the 1990s who played a searing reunion set on the Mempho Presents stage. Tyler Keith, who co-fronts the band, brought his larger than life stage presence to the small stage, exclaiming “let’s have a moment of NOISE.” Mid-afternoon latecomers turned their heads and drifted over for a face full of Mid-South punk. As purveyors of ragged-but-right garage rock, they were the only band who offered that sound at the festival this year — and the only band who could have offered that sound, though Deaf Revival brought their own brand of chunky molten metal to the same stage earlier that day.

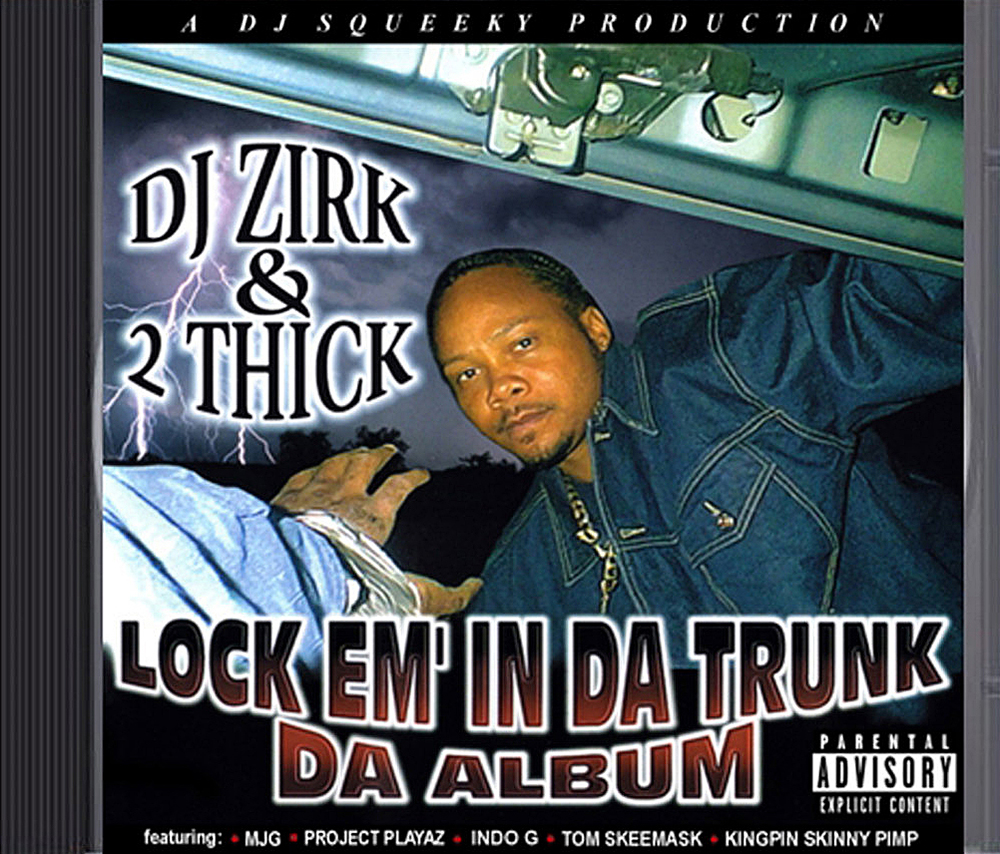

Then it was finally time for Public Enemy. In a weekend full of classic hip hop acts, PE stood out for the cultural impact and razor sharp live set. Memphis-based multi-instrumentalist Khari Wynn, who used to be PE’s musical director, opened the set with a Hendrix-inspired take on the Black national anthem, James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” It was a gripping reminder of the historical sweep of Public Enemy’s aesthetic, and Wynn’s presence in the band for the rest of their set only toughened up their sound.

Chuck D and Flava Flav were in rare form. Chuck D called Busta Rhymes and Ludacris “our nephews,” rapped over AC/DC samples, and delivered epic readings of “Welcome to the Terrordome,” “Shut ‘Em Down,” and their 2020 anti-Trump anthem “State of the Union (STFU).” During “He Got Game,” Chuck D amended the line “fuck the game if it don’t mean nothin'” to “fuck the president if he don’t mean nothin’,” to wild cheers.

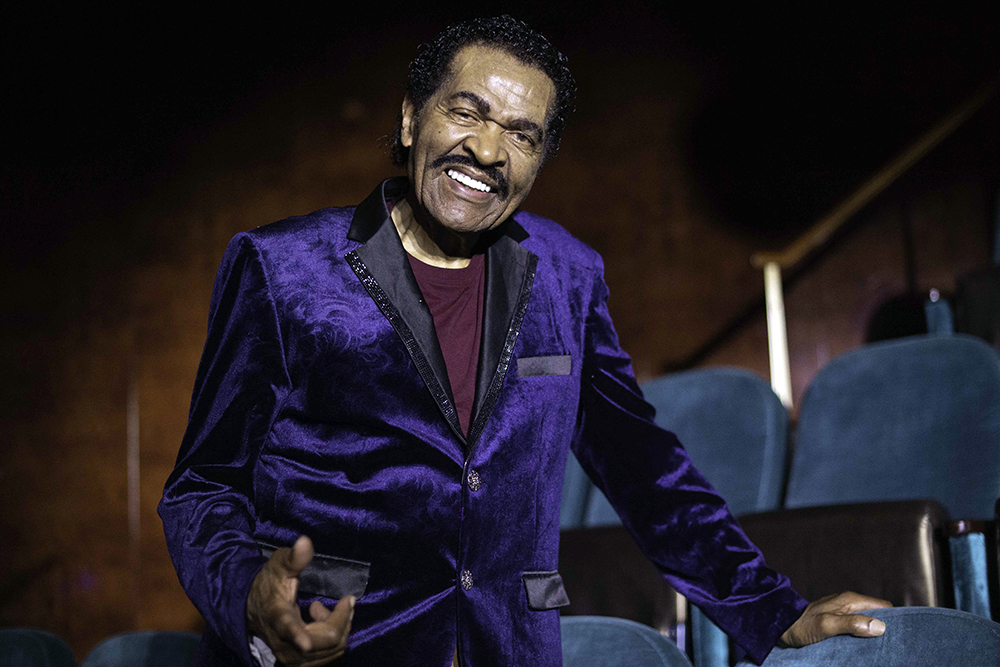

Public Enemy truly embraced Memphis as well, with Chuck D saluting both the Mid-South Coliseum and the great Isaac Hayes, and referring to his bandmate, Flava Flav, as the “heir apparent of Rufus Thomas.” The set concluded with a welcome message of unity from The Flav, who exhorted the crowd to raise peace signs.

After the intense workout of Public Enemy, The Killers, one of the slickest and most popular bands on the planet, had their work cut out for them. Perhaps that’s why they opened with “Great Balls of Fire,” which they had clearly learned in soundcheck. It was a humanizing moment, reminding us that, for all of the expensive production values and Vegas residencies, The Killers are, at their heart, a rock band coming home to the holy city of rock and roll.

And, it must be noted, The Killers represented the “live bands over pre-recorded tracks” concept well, especially guitarist Dave Keuning. The triumph of pure musicianship continued on the festival’s closing day as well. One reason for that was the focus on down-home gospel at the Mempho Presents Stage, starting with octogenarian Elizabeth King, still as powerful as ever, accompanied by her son Zack McGhee on bass, drummer Tavion Robinson, as well as Will Sexton on guitar and (Memphis Flyer music editor) Alex Greene on keys. Later, the Jubilee Hummingbirds also appeared, before The Wilkins Sisters brought the house down for the day.

The Wilkins Sisters and Salo Pallini, the quirky, genre-defying instrumental combo, were the only local bands to be featured in both last year’s and this year’s RiverBeat, but the latter made their big stage debut this year. For this year’s RiverBeat, they had the welcome addition of singer Alexis Grace, who added shimmering texture to the songs from their album Sirens of Titan, then blew the crowd away with a soulful rendition of Portishead’s “Sour Times.”

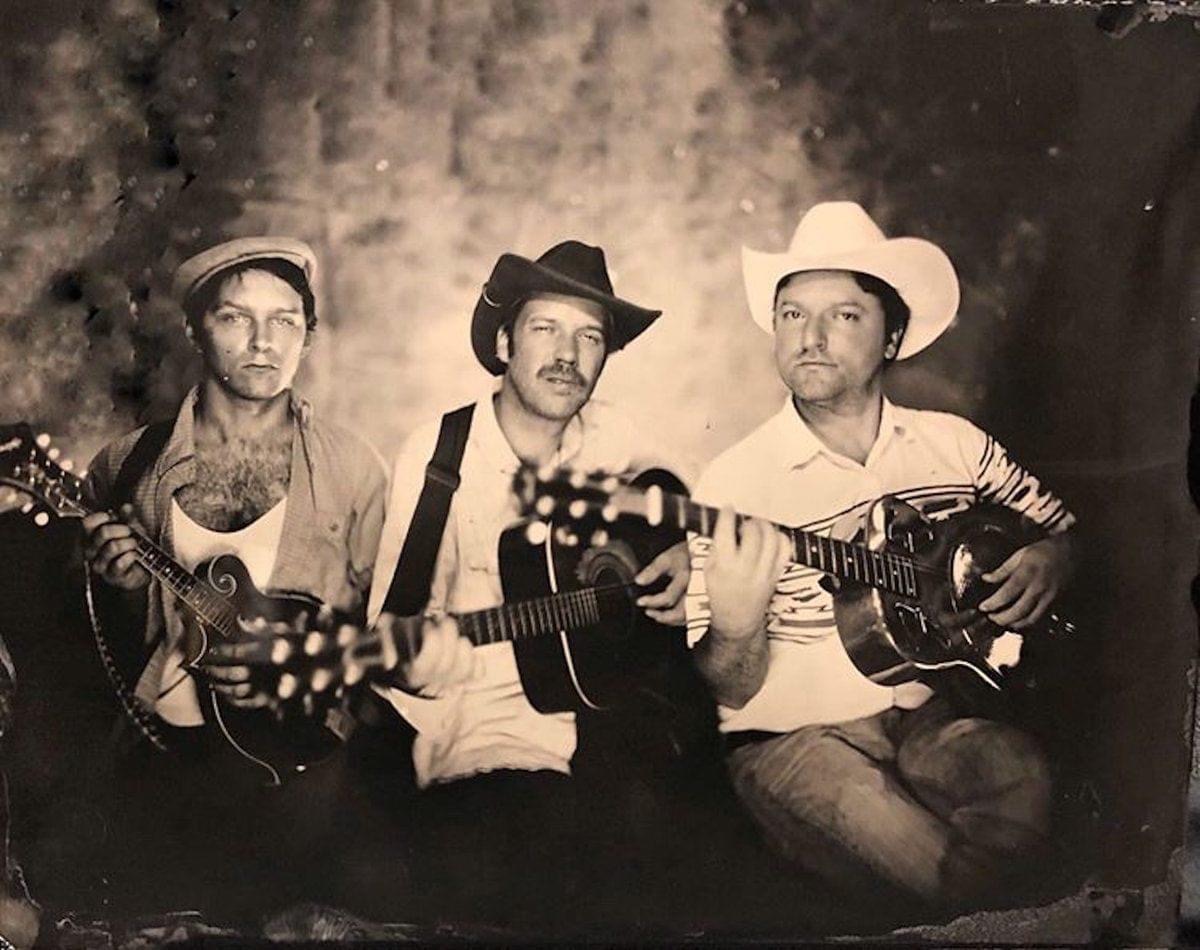

They were followed on the Bud Light Stage by one of the great revelations of RiverBeat, La Lom, a trio of ace players from the City of Angels (and it’s been said their name indicates they’re an “L.A. League of Musicians”). Their subtle and surprising instrumentals captivated the afternoon crowd with no effects, fireworks, or grandstanding — just finely-tuned musicianship of the grooviest, slinkiest kind.

The best double feature of the festival involved running back and forth from the Bud Light stage to the Pavilion stage on Sunday afternoon, trying to catch both Texas glide-rockers Khruangbin and Afro-beat legend Sean Kuti and Africa 80. Khruangbin’s soaring but simple instrumentals were flawless and precise, drawing a huge crowd. With a captivating, retro set design, moody lighting, and subtle choreography, they had the crowd in the palm of their hand with the inspiring musicality of their arrangements.

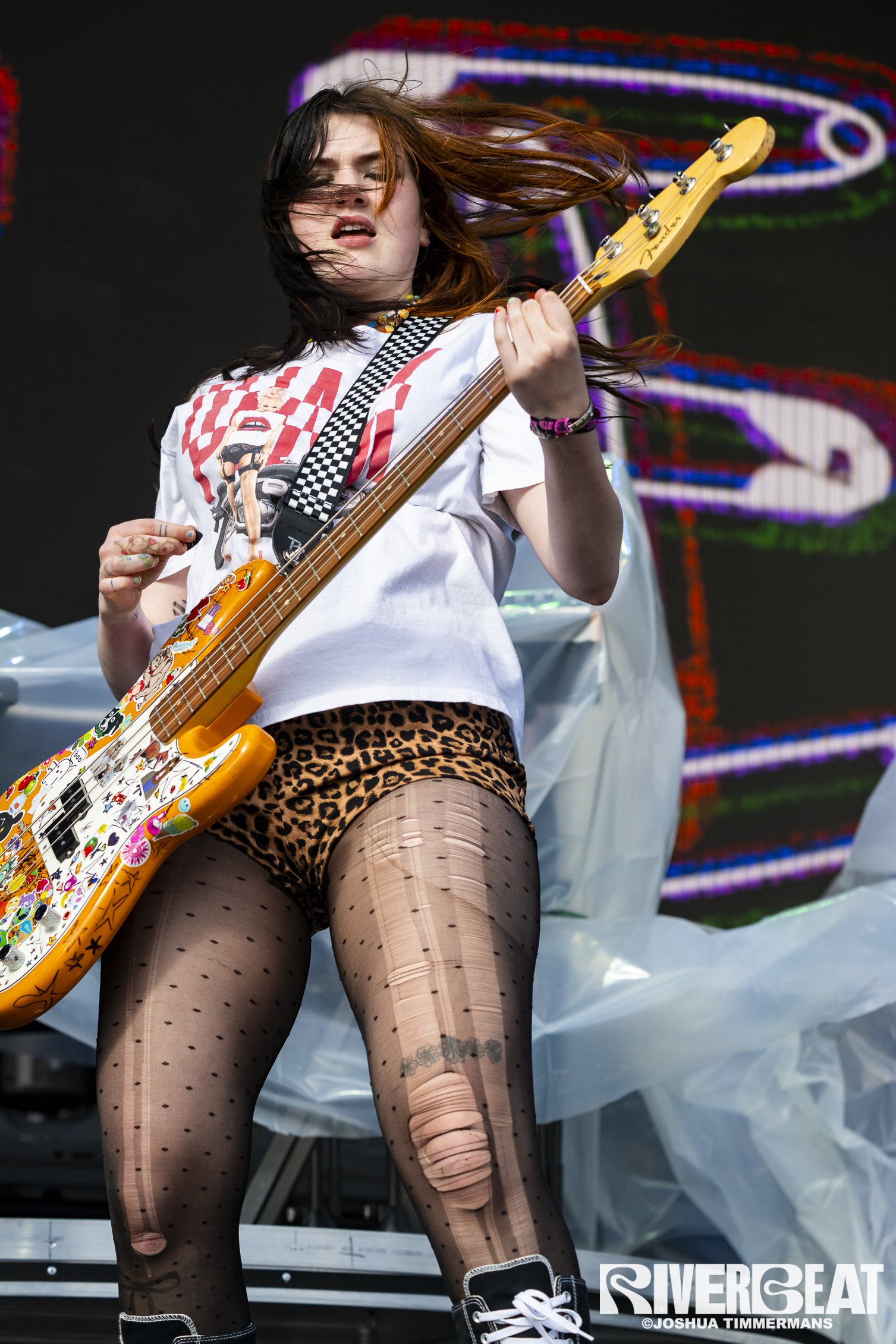

Moreover, Khruangbin’s bassist, Laura “Leezy” Lee Ochoa, who was dressed for Wimbledon but had moves akin to Tina Weymouth’s shimmies with the Talking Heads, was but one of the badass female bassists at the fest this year, the other being Gayle.

With a huge, rocking stage presence, she wielded her four-string axe like, well, an axe, and exuded pure pop-punk rage, especially when lamenting an ex in her 2022 hit, “Alex.” “I gotta break up with Alex/It’s gotten way too dramatic … Ba-da-da-da-da!” Admittedly, some of our sensitive writers at the Flyer found such lines both triggering and oddly alluring.

Meanwhile, Sean Kuti battled through Khruangbin’s sound bleed to get his crowd moving. Kuti, the 42-year-old son of Afrobeat originator Fela Kuti, bounced from player to player, calling for solos over the twisty, infections beats from his rhythm section. He is legit one of the best front men in the business, and has been for years.

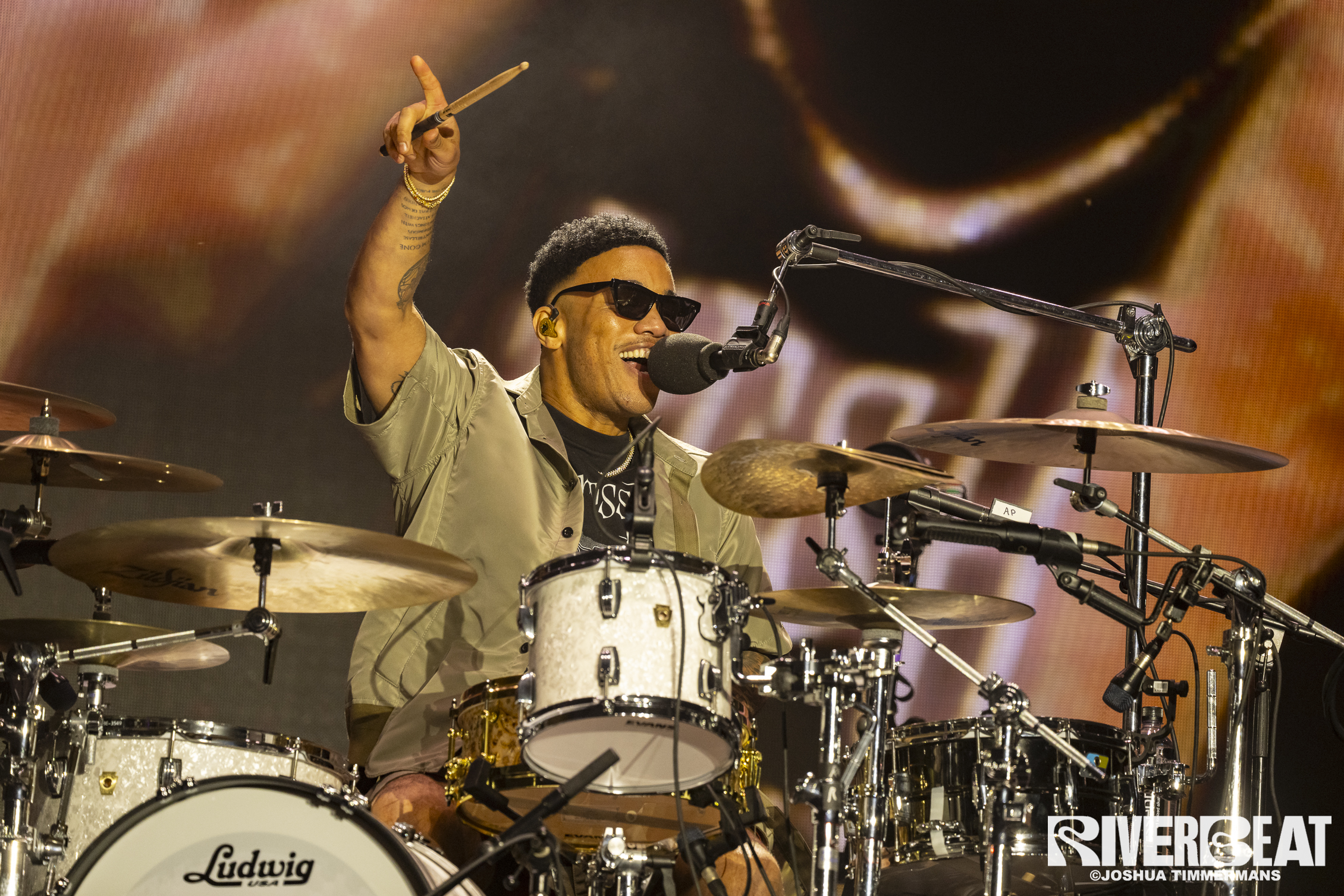

And finally, speaking of the highest standards of musicianship and a commitment to featuring a live band, Anderson .Paak & the Free Nationals brought the weekend to a perfect close with some inspired playing. As .Paak exclaimed halfway through the set, “I still believe in real instruments played by real people and fuck that AI shit!” And his drumming alone revealed the power of such an approach. But he also brought the charisma and humor of a born performer, even appearing in drag at one point as he belted out some soulful R&B, before settling into a look more reminiscent of L.L. Cool J for the rest of the show. His set was a tour de force, and the people lingering late Sunday night didn’t want RiverBeat to end.