One of my first questions for director Chris McCoy after watching Antenna was what punk rock means to him today. To this, he responded, “I don’t know. What do you think punk rock means today?” Being born in the 2000s, I don’t think I have ever really listened to punk. Not being born in Memphis, I had never even heard of the legends from the Antenna club, until I watched McCoy’s documentary.

The story of the Antenna is told through the many faces of punk rock, including writer and stealth narrator Ross Johnson, director Chris McCoy (who is also the film and TV editor for the Memphis Flyer), editor/producer Laura Jean Hocking, Antenna club owner Steve McGehee, and former Flyer music writer John Floyd. All together, this team took three years to create the documentary. Hocking details the beginning stages of the film where they started “with more than a hundred hours of archival footage. We had 1,100 still images and 88 interviews, some of which were three and four hours long.” Hocking describes her editing process as “a big project that at the time, when I was making it, I had a lot of nervous breakdowns.”

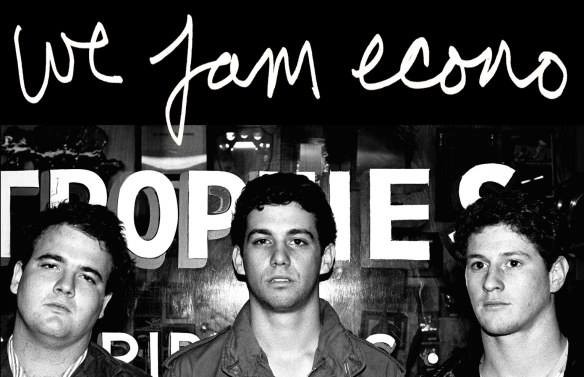

The inspiration behind Antenna was McCoy’s desire to tell “a story about Memphis that needed to be told, that had not yet been told.” This was the story of the Antenna, a punk rock club that stood on Madison Avenue from 1981 to 1995, a forgotten era of Memphis music — specifically Memphis punk rock music. McCoy calls it a “weird mutant strain of music that grabs little bits from a whole bunch of different kinds of music.”

As such, the Antenna club was “a place where you could be weird,” Hocking says. The club was not your usual Beale Street bar but an eclectic refuge where outsiders, weirdos, gays, and anyone without prejudice could be their authentic selves. Especially in its early days, Antenna’s punk rock spirit made it a place for experimentation, dedicated to the fight against conformity. A specific example McCoy uses is “one of my favorite shots in the movie is the video we found of that dude heckling The Replacements, saying, ‘We don’t care how famous you are!’ That’s the essence of the entire club right there in one moment.”

Between the crime, the poverty, and the political turmoil, Memphis can sometimes seem cursed and hopeless. This is even mentioned with Johnson’s opening line of the film: “Memphis is cursed.” McCoy comments on this idea saying, “I always call Memphis your drunk uncle. I can complain about him and what a deadbeat he is, but nobody else can say something about it.” This spirit is encapsulated in the Antenna’s story, in “the story of those musicians who are still here and who didn’t get the recognition that they deserved,” McCoy says. Indeed, the Antenna club hosted various artists like R.E.M., Big Ass Truck, The Panther Burns, and The Modifiers, but these are just some of the artists that defined the era of punk rock and the resistance against conformity.

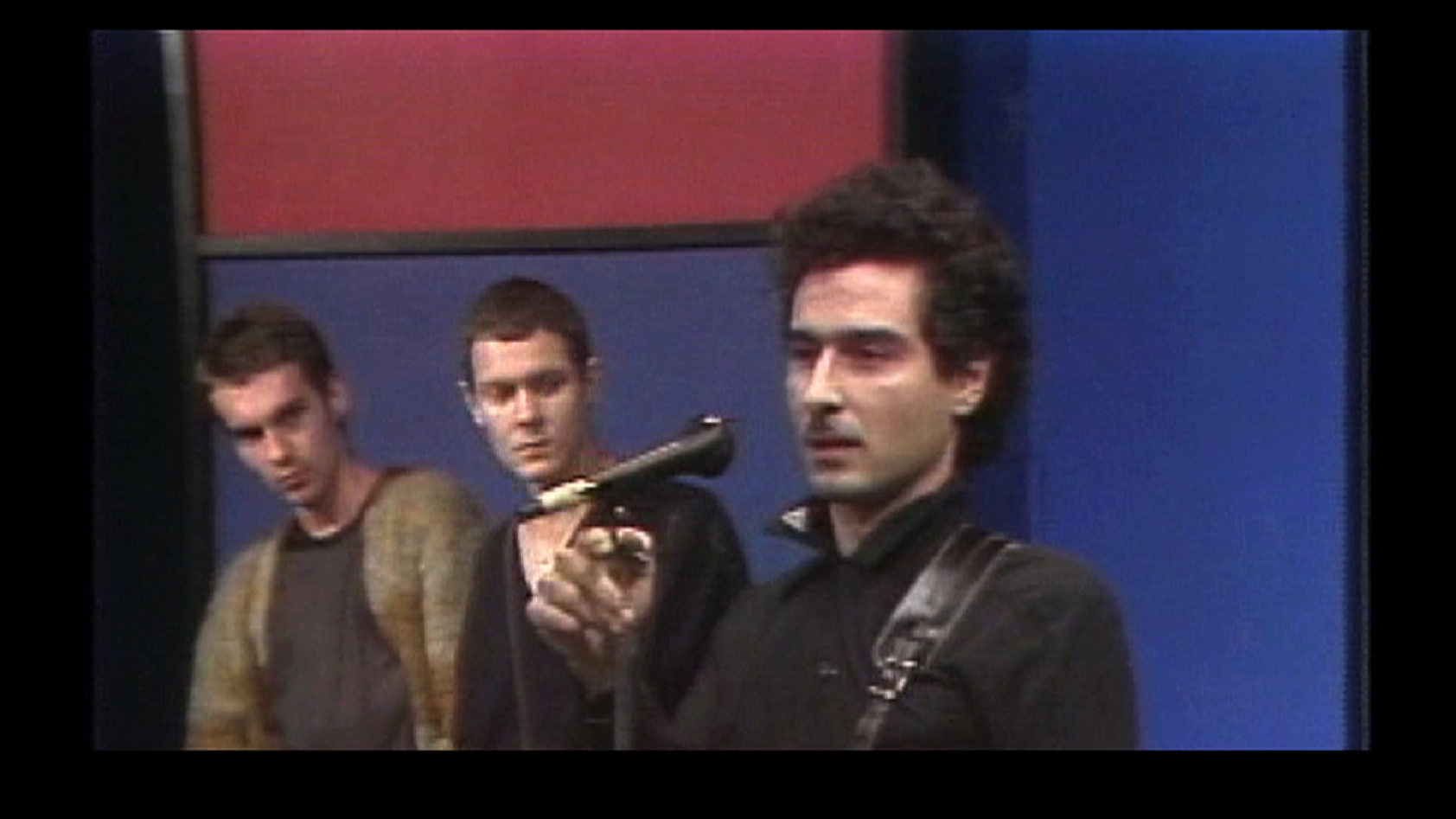

Outcasts like Milford Thompson, Melody Danielsen, Alex Chilton, and The Klitz were able to express their true selves to the world. When daytime talk show host Marge Thrasher told The Panther Burns they were “the worst thing that ever came out on television,” bandleader Tav Falco just smiled. The Modifiers took pride in being “the most hated band in Memphis.” They were simply just, being themselves, and any hate or fear simply fell at their feet as they performed. “The attitude was, we dare you to like this music,” says McCoy.

This film is truly a labor of love and takes the audience back to the time where music not only united a community but also created a place to escape from the prejudices of society. McCoy remembers “hanging out at the Antenna from ’89 to ’95, when it closed.” Watching the film, I understood what it might feel like to be transported back to the ’80s, with a front row seat at the Antenna. Hocking says this was intentional. “We wanted you to feel like you’re at the club or hanging out with these people or in a round table discussion with them.”

Framing the film this way makes for a very intimate connection with something that to me, previously seemed foreign. Throughout the film, I found myself identifying with the Antenna crowd and their love for a place that shielded them from the rest of society. Seeing the many faces of punk rock and former Antenna attendees profess their love for the Antenna club, made me wonder if there was anything similar to the Antenna club today. When the film ended, I felt like I had just been to my first and favorite rock concert in my life.

Antenna speaks for itself with its continued and growing popularity even after its premiere 10 years ago in 2012 at the Indie Memphis Film Festival. The film has been awarded the Audience Award, Special Jury Prize, and other various awards at the Oxford Film Festival, and it is recognized as one of the most popular films in the 25 year history of the Indie Memphis Film Festival. Although the film has an immense love among its audience, it cannot currently be released commercially because of issues with obtaining music rights for the 50 different songs present in the film. McCoy and the film’s producers have spent the last 10 years trying to raise money to pay the artists for their songs and give them the recognition they deserve. Despite several investors’ and distributors’ interest in the film, fundraising efforts have always come to a halt and been unsuccessful. Thus, the film can only be caught at film festivals and on rare occasions.

The next screening of this film will be on Friday, October 21st, 8:45 p.m., at Playhouse on the Square during the Indie Memphis Film Festival to celebrate the film’s 10-year anniversary. Tickets ($12/individual screening) can be purchased online or at the door if not sold out already.