First of all, Black Widow should have happened five years ago. It took eleven years — from Iron Man in 2008 to Captain Marvel in 2019 — for Disney super-producer Kevin Feige’s Marvel Cinematic Universe to make a solo super-movie starring a female superhero. In the interim, Warner Brothers filled the void with 2017’s Wonder Woman, the only good movie made from a DC property in a decade.

Considering how aggressively mediocre Captain Marvel was, it’s especially galling that it took so long for Scarlett Johansson to get her own starring vehicle as Natasha Romanoff From a character standpoint, Natasha is the most interesting of the Marvel A-team. Trauma has always inflected the best superhero origin stories. (Did you know Batman’s parents were murdered in front of him? Someone should put that in a movie.) She was trained from childhood to be an elite assassin and intelligence operative by the Red Room, a secret Soviet super-soldier program notorious for its brutal methods. Somehow, the stone cold killer’s conscience survived the ordeal, and she defected to S.H.I.E.L.D., where she became Nick Fury’s most trusted confidant. Alone among the Avengers as a non-super-powered (albeit surgically enhanced and relentlessly conditioned) human, she feels pain when she gets hit. Thor the space god is cool, but he’s one-note. Natasha’s adamantium-tough exterior hides a broken person, deprived of human connection, riven with guilt for all the “red on my ledger,” trying to balance the books with world-saving good deeds. But she’s always gotten short shrift. During The Avengers iconic Battle of New York, the prototype for all the Marvel Third Acts to come, Black Widow was fighting flying, laser-firing aliens while armed only with a pair of pistols. Couldn’t S.H.I.E.L.D. at least get her an assault rifle?

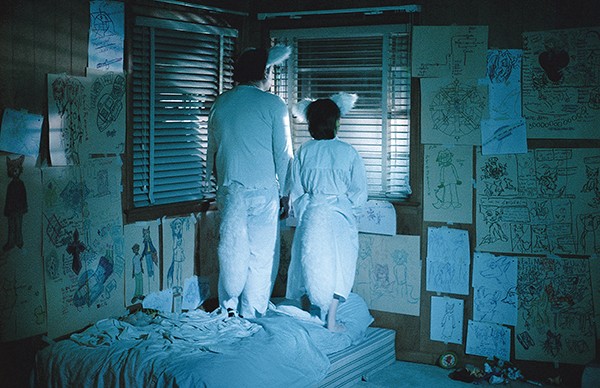

Natasha’s emotional potential is realized in Black Widow’s unexpectedly moving cold open. It’s 1995, and she’s living in suburban Ohio with her mother Melina (Rachel Weisz) and sister Yelena (played as a 6-year-old by Violet McGraw). Just as they’re about to sit down for an ordinary, wholesome family dinner, father Alexei (David Harbour) comes home with bad news. Turns out, the family are deep-cover spies, and their cover’s been blown. As the fake family rushes to get to the escape plane to take them to Cuba, Natasha stares longingly out the window, saying a silent goodbye to the closest thing to a normal life and human connection she will ever have. Her family may be fake, but it felt real to her.

Fast forward to 2016. (The film itself recognizes that it’s late. Natasha died in Avengers: Endgame, so Black Widow’s story takes place while she was on the lam after the events of Captain America: Civil War.) Yelena (played as an adult by Florence Pugh) is hunting a target who turns out to be another member of the Black Widow program. After Yelena strikes a mortal blow, the dying Widow exposes her to a red gas that undoes the chemical mind control regime the Red Room has imposed on her. Yelena goes rogue, stealing the remaining doses of Widow antidote, and sending them to her estranged, faux-sister Natasha for safekeeping. Instead of spending her downtime watching Moonraker — naturally, Natasha’s an obsessive James Bond fan — she decides to track down Yelena, and the pair team up to kill the Red Room mastermind Dreykov (Ray Winstone) and dismantle the Widow program once and for all.

With director Cate Shortland at the helm, Black Widow is the best superhero picture since Black Panther. It’s not just an acceptably entertaining Marvel product, but an actual good film in its own right. The second-act action set piece, when Natasha and Yelena break their pretend-father Alexei out of a Siberian prison, stands with the airport brawl from Civil War as an all-time, kinetic highlight of comic book cinema.

It’s Johansson’s movie (she’s executive producer), but she leads an ensemble cast. Natasha’s been making life-or-death decisions since she was a teenager, so Johansson plays her with a deep world-weariness. She has zero time for petty bullshit; in 2021, I find Natasha’s emotional exhaustion extremely relatable. Pugh is her kid-sister foil, knowing exactly where to needle to get a rise out of the ice queen. The comic relief is left up to Harbour as the Red Guardian, Captain America’s Soviet counterpart gone to seed, still bitter about losing the ideological struggle with the West.

Black Widow’s ideology is overtly feminist. It’s a quintessential female gaze movie. The women are sexy, but not subject to a leering camera; the men are either buffoons or sniveling abusers. The stakes and scale are remarkably restrained by Marvel standards. Natasha, a subject of unthinkable patriarchal abuse, is fighting to give other victims the kind of agency she was denied. Left to her own devices, Black Widow doesn’t choose to save the world from xenocidal aliens. Her heroism serves a more practical, down-to-earth purpose.