Do you have one of those movies that has been sitting in your Netflix queue forever? You don’t remember how it got there, or why you wanted to watch it in the first place, but either you never bothered to delete it or you checked the info periodically and said, “Oh yeah. That’s got so-and-so in it.” Or “Uncle Jack thought we would like that,” or something similar. Well, I have several dozen of those movies on my Netflix queue. Maybe it’s a form of digital hoarding, but I wouldn’t know, since none of my long-term queue sitters is a psychologically manipulative reality show like Hoarders.

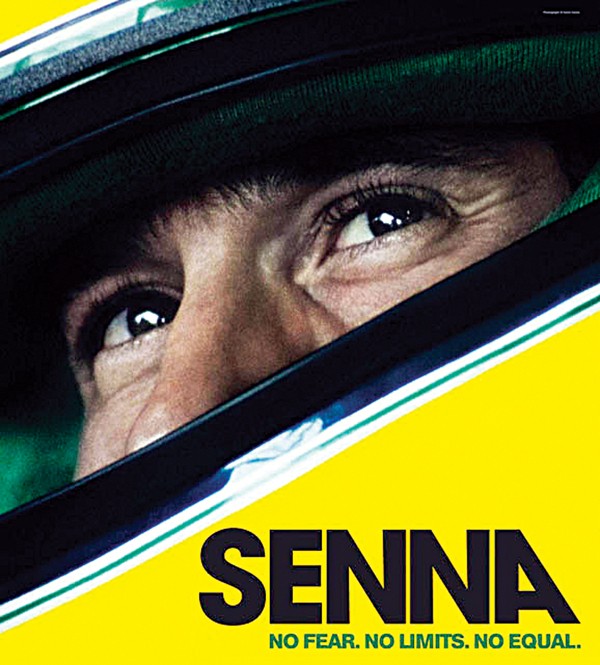

For me, one such hoarded movie was the 2010 documentary Senna. I don’t know how I heard of it or how it got into my queue, but I do know it had been there for a long time. Way before that time I got obsessed with Universal and Hammer horror movies and littered my list with The Mummy Returns, Black Sabbath, and The Invisible Ray, Formula 1 driver Ayrton Senna had been staring at me with his steely eyes as I flipped by him on my way to my complete rewatch of all seven seasons of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. (It still holds up, by the way). Maybe it was supposed to be part of my research into the Antenna documentary, but once that was over, I never wanted to watch another documentary in my life. But recently, once my filmmaker’s PTSD had abated a little bit, I finally decided to watch Senna. I wish I hadn’t waited so long, because it is brilliant.

Director Asif Kapadia chose to make the film without any talking head interviews, narration, or recreations. Instead, the story is told through vintage footage of Senna’s races and contemporary interviews with the driver, his family, and his rivals. There are a few interviews that were obviously done for the film, but they are only voice overs. Everything on the screen dates from either Senna’s childhood or his time on the track from 1984 until his death behind the wheel a decade later. Kapadia is able to do this because Senna, while not well-known in the NASCAR-obsessed United States, was, at his peak, one of Formula 1’s biggest stars. He was a national hero in his native Brazil, and almost everything he did, both on and off the track, was filmed. The amount of footage Kapadia and his 13-member editing crew, led by Chris King and Gregers Sall, had to work from is mind boggling, but they succeeded in organizing it all into a comprehensible and propulsive 106 minutes.

Senna’s interest in racing began in go-karts before graduating to the big show at age 24. He was personable, good looking, and immensely talented, which made him an instant media darling. He was also completely obsessed with racing and focused his entire life around winning the Formula 1 World Championships. This made for thrilling narratives for the fans but left his personal life seeming hollow. In 1988, he was asked to join the prestigious McLaren team, where he and his teammate Alain Prost dominated the sport, and he won his first championship. But in his second season with McLaren, jealousies flared, and he and Prost slid from friendship into bitter rivalry. In the final race of the season, Prost, who was slightly ahead in Formula 1’s confusing points system, deliberately rammed his car into Senna’s, taking them both out of the race and claiming the championship for himself. The next year, Senna thirsted for revenge, and he got it at great personal cost.

Kapadia’s remarkably clear direction traces Senna’s personal development from fresh-faced idealist fighting the Formula 1 bosses, to successful superstar to cynical competitor. At 33, he was an elder statesman of his sport; at 34, a martyr to its dark gods. Kapadia’s race sequences, culled from hundreds of cameras, are both coherent and thrilling. Senna’s career spanned a time of major leaps in video technology, so the steadily improving images trace the passage of time. Since miniaturized in-car cameras were developed in the late 1980s, Kapadia lets the damaged tape of Senna’s final lap play out in full, its encroaching video noise becomes symbolic of the dissolution of a life played out on camera.