Every year around Halloween, I get a hankering for Hammer horror. Atmospheric films like The Gorgon or Christopher Lee’s Dracula, made before slasher pictures gave the genre a bloody sameness, have a certain pleasing gothic creepiness that transcends their screenplay and acting faults. The Witch, which won Robert Eggers a directing award at last year’s Sundance Film Festival, seems like it was created out of the Platonic ideal of a Hammer-period horror film, with all of the creep and none of the camp.

It begins with a family of five being expelled from an unnamed New England plantation that looks a lot like Salem circa 1690. The cause of the schism is some obscure doctrinal dispute between the family patriarch William (Ralph Ineson) and the town council of puritans led by the Governor (Julian Richings). Significantly, it is William who denounces the townspeople as being insufficiently pure, claiming his family are the only ones who practice true Christianity.

Ellie Grainger, Black Phillip the Satanic goat, and Lucas Dawson struggle to survive.

William takes his wife Katherine (Kate Dickie), daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), tween son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), elementary-aged twins Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), and infant Samuel into the forest to build a new life for themselves where they can worship free from the corrupting influences of the world. But the woods they chose for their new home already has an inhabitant: a shapeshifting witch played in various forms by Bathsheba Garnett and Sarah Stephens.

A card at the end of the film notes that it was based on historical accounts of witchcraft trials from the late seventeenth century, when there weren’t any witches with magical powers, just women whom the patriarchy had deemed too unimportant to feed and who used the magical thinking of theology to justify getting rid of. But there’s no doubt black magic is real in the world of The Witch: No sooner has the family built their farm than the witch snatches baby Samuel in the midst of a peekaboo game with Thomasin, grinds him up, bathes in his innocent blood, and goes for a flight on her broomstick.

The family is grief-stricken, with the burden falling heaviest on the mother, Katherine, who struggles to stay upright as conditions on the farm worsen. The crops are failing, and the animals are either getting sick, or, in the case of the huge goat named Black Phillip, developing a Satanic mean streak. Suspicion falls on Thomasin, the beautiful young daughter who is coming of age and inadvertently tempting her little brother with lustful thoughts. Taylor-Joy is riveting as the noose tightens around her, causing herself to question her own innocence. The high point of her performance comes when, pressured by her father to give a false confession, she snaps and suggests that maybe the reason why his farm is failing and his kids are dying is that he’s an arrogant religious nut who sucks at farming and is generally unprepared for the harsh life of the frontier.

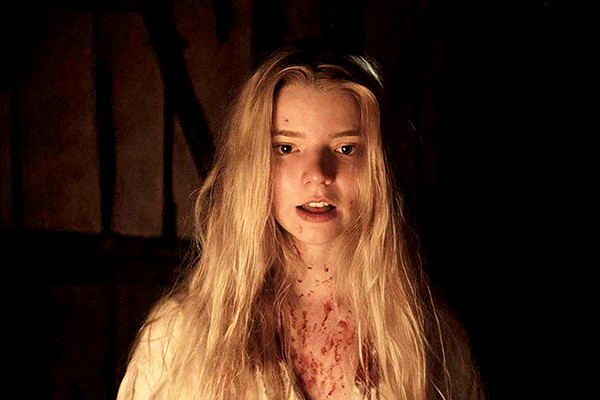

Anya Taylor-Joy as accused witch Thomasin

From the safe and rationalist point of view of the 21st century, that sounds like a pretty accurate description of the conditions surrounding the Salem witch trials, but The Witch’s point of view is stuck firmly in the puritanical 17th century, where witches are real and want to do the devil’s bidding by messing with good Christians. The Witch of the Woods sinks her talons deep in William and systematically deprives him of everything he holds dear. It’s an epic slow burn that makes flawless use of the film’s 93-minute running time. Like the ornate Hammer films of the early 1960s, the production design puts us in the characters’ world from the beginning, but Eggers is going for a strict realism that makes the magical elements more creepy and unnerving. The low-light photography of Jarin Blaschke, such as the extended sequence around a tense dinner table lit only by dripping, homemade candles, takes a page from Kubrick’s groundbreaking work on Barry Lyndon and transforms the domestic scene into a Dutch Masters painting.

The controlled, almost serene pacing of The Witch goes against the grain of contemporary horror, but, taken with work like last year’s instant classic It Follows, it seems to point toward a new subgenre of arthouse horror. For fans of the creepy, it’s the year’s first must-see movie.