Midway through I Am Not Your Negro, director Raoul Peck takes a moment to give us a peek at author James Baldwin’s FBI file. According to the G-Man who wrote the memo, Baldwin was a black agitator, a homosexual, and a “very dangerous individual.” By this time in the film, we have gotten to know Baldwin beyond just the usual blurb points: the guy who wrote The Fire Next Time and Notes on a Native Son, parts of which you might have had to read in school during Black History Month. The FBI is supposed to deal with murderers and criminals, and the erudite, quietly passionate man the documentary audience has seen chatting with Dick Cavett and debating at Cambridge University does not look like someone the FBI would describe as a “dangerous individual.”

But Baldwin would have instantly understood why J. Edgar Hoover’s boys were afraid of him. “The root of the white man’s rage is terror,” he says a few moments later, of a figure “who lives only his mind.”

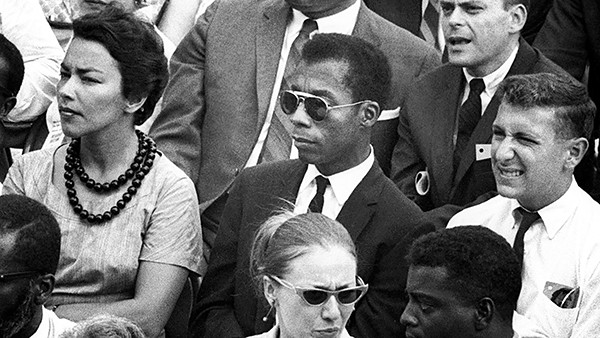

Baldwin is a fascinating figure of the civil rights era, but in recent years he hasn’t gotten as much attention as leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. Part of that might be that he came along earlier than the others — his first novel was published in 1953, when King wasn’t even a pastor yet and Malcolm had just met Elijah Muhammad. For Baldwin, the writer’s life meant being an observer. He was neither a Christian nor a Muslim nor a member of the NAACP, but first and foremost a man of letters. Still, it was hard to maintain his objectivity in the waning days of Jim Crow. In a televised debate from the early 1960s, Baldwin found himself between Dr. King and Malcolm X as they outlined their competing visions for black liberation in America. The excerpts chosen by Peck for the documentary are extraordinary, both for the power of the two men’s personalities and the clarity with which they speak (especially in an era when a president can respond to allegations of treason with “No puppet! You’re a puppet!”). “The line that divides a witness from a participant is a fine one,” Baldwin would later say about his time in the civil rights struggle.

Both Malcolm and King would be dead before the decade was out, but Baldwin would continue to write well into the 1980s. In 1979, he wrote a 30-page outline for a book that would be called “Remember This House,” where he proposed to outline the struggle through the stories of three martyrs: King, Malcolm, and Medgar Evers. The book was never completed, but Peck took the framework, added quotes from Baldwin’s massive corpus, and layered in some choice archival footage to create I Am Not Your Negro. Samuel L. Jackson reads Baldwin’s words in something that is not quite an imitation of Baldwin, but quite different than the actor’s usual speaking voice. Jackson’s virtuosic voiceover performance is a reminder that one of America’s greatest living actors has been relegated to a caricature of himself while white actors his age still get juicy parts. This would not surprise Baldwin, who hated Stepin Fetchit and revealed to white audiences that black people disliked the Academy Award-winning 1967 film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, because they thought Sidney Poitier was “being used against them” to neuter their movement. There are choice revelations like this about every five minutes in I Am Not Your Negro.

We’re in the middle of what has been called the Golden Age of Documentary, but cultural docs have triumphed at the Oscars every year but one this decade (the exception being 2014’s Citizenfour). This year, however, an issue documentary is almost assured to win. On the race relations front, I Am Not Your Negro is nominated alongside Ava DuVernay’s 13th and OJ: Made in America, while Fire at Sea takes on the Syrian immigrant crisis in Europe. I think it’s unlikely that Academy voters will choose the refined rthymns of I Am Not Your Negro over the epic sprawl of OJ: Made in America, but that doesn’t mean that Peck’s work is less worthy. Thirty years after his death, Baldwin’s words and deeds still speak to an America that needs to listen.