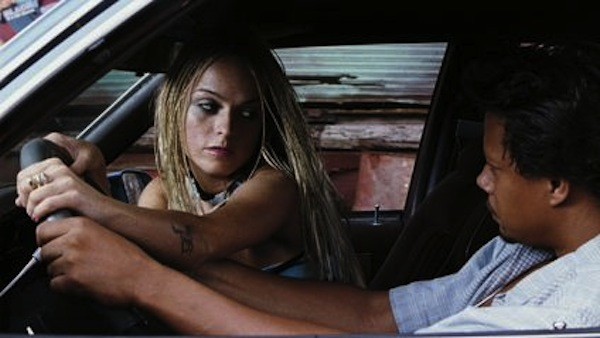

Terrence Howard as DJay in Hustle & Flow

We’ve reached the final week of our Thowback August, where we look at movies that came out in 2005. From a Memphis perspective, the biggest film of that year was Craig Brewer’s Hustle & Flow. It was the culmination of an indie film scene that had been brewing in Memphis since the mid-90s, and it’s still the quintessential indie success story: A filmmaker from nowhere with little but raw talent and determination makes a movie about his town and gets the Hollywood machine to take notice by not only winning at Sundance but also getting his star an Academy Award nomination and his soundtrack an Oscar for Best Song.

In the decade since then, Brewer has been working steadily in Hollywood. He has directed two more films, 2007’s Black Snake Moan and 2011’s Footloose, but he has also been much in demand as a writer and producer. Next year, a new version of Tarzan will be released that began life with a script he wrote and was originally attached to direct. He is currently working for Paramount Pictures developing ideas for television series, including an adaptation of the studio’s 1980 film Urban Cowboy which has been fast tracked by Fox to premiere next year. He also just finished directing an episode of Empire, the most popular show on television, which not coincidentally stars Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson, the two leads from Hustle & Flow.

Brewer has been a tireless and generous mentor to many in the Memphis film community. He provided extremely helpful feedback and advice during the production of my documentary Antenna, and since then, I have had the privilege of working with him on several projects as a writer and researcher. He is currently in Los Angeles working on Urban Cowboy, so last Sunday, I gave him a call to talk about Hustle & Flow from the perspective of a decade later. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and relevance, but not for its epic length.

Al Kapone, Craig Brewer, and Terrence Howard on the set of Hustle & Flow

Does it feel like ten years?

There’s times when it feels like it’s really far away, that it happened a lifetime ago. Then there’s some times when it feels like just yesterday. You know when I was directing Empire, and on set with Terrance and Taraji, I felt like I was right back in the saddle doing Hustle & Flow. There’s a rhythm between me and Terrance that I had forgotten about. He’s such an intuitive actor. It’s not so much that you want to tell him what to do, as you want to provide him with options and see what kind of magic there is. I always felt that particular type of directing—I don’t even know if you want to call it directing, it’s more like wrangling—was very much a Jim Dickinson way of doing things. It’s more about getting a bunch of artists in a room together and watching the magic happen instead of specifically trying to hit something that was pre-determined. That’s what I feel when I direct someone like Terrance.

Everybody’s talking about how Empire was the sequel to Hustle & Flow, but maybe we should just do another Hustle & Flow. DJay didn’t become a millionaire, I can tell you that.

But I think for me, what the ten years means to me is, you’re constantly chasing that first high. That’s why I’m getting into doing television. It’s new, you’re racing constantly, struggling to stay ahead, and you’re constantly riddled with self-doubt and terror.

So that doesn’t go away?

No, it doesn’t.

I remember a few years back Hustle & Flow was playing at The Orpheum. I went to see it, because I hadn’t seen it in a long time. I remember sitting in the audience and allowing myself to enjoy the fact that I know Hustle & Flow has kind of made it. It didn’t just become a movie, or win an Academy Award, a lot of people have seen Hustle & Flow around the world, and they dig it. You can quote it, and people know what you’re talking about. There are still references to Hustle & Flow constantly.

I still see “Hard Out Here For A Pimp” references all the time.

Or “Hard Out Here For A _________”

You’ve been meme-ified. That’s the highest compliment an artist can be paid in 2015.

And everything that’s happened with the Grizzlies, with the audience chanting “Whoop That Trick”… I was sitting there as the movie was beginning, and I was watching it differently than I had ever watched it before. I wasn’t wondering, ‘Will this moment land?’ I’ve been in audiences where they didn’t clap after “Whoop That Trick”, and I’ve been in audiences where they do. But I didn’t do any of that. I was sitting there thinking, “OK, you know movies. Try to figure out why people like this film.” I think I kind of came up with two things, primarily. I don’t think there’s anything more addictive than watching people create something. Whether or not you’re into that particular thing, be it music or pulling off a plan or building something, you’re seeing their excitement and struggles. It’s very accessible. A lot of people on this planet, and some time in their lives, say “I think I want to try to pull of this particular thing. Then you struggle, and you doubt, and you have mini-successes, and you have collaborators who become friends. And you might get a victory, or you might not. But there’s something about watching the effort of art, the effort of creation, that is pleasing. And I think in Hustle & Flow, watching them make “Whoop That Trick” and “Hard Out Here For A Pimp”, and performing “It Ain’t Over For Me”, and watching them build their studio is exciting.

The ‘Whoop That Trick’ scene.

The second thing that I figured out about the movie—and this may sound obvious, but I wasn’t aware of this was happening while I was writing it—is this up-and-down nature of the character of DJay. You start off, and he’s saying this monolog that sounds kind of profound, and you kind of like him, then you realize he’s a pimp and he’s talking some naive prostitute into climbing into a car with a guy. You see him get together with Anthony Anderson and they start building a recording studio and there’s all this excitement, and they make a song, and you think, ‘Here we go!”. Then he comes home and throws Lexus and her baby out of the house. And you think, ‘Why’d he do that? I don’t know if I like him any more.” Then you see them try to make “Hard Out Here For A Pimp”, and they’re trying to get a sound our of Shug, and maybe he’s looking at her differently, with some respect, and love, and there’s a victory. But then they need a microphone, and he needs Nola to go in and service a guy at a pawn shop, and you’re like “Ugh. I hate him again.” It’s this up and down of “I like him, he’s disappointing me. I like him, now I hate him. I like him, now he’s doing something stupid.” Then you get to that point where he pimps Skinny Black into taking his demo, and you’re like, “Finally!” And to hear the groans in the audience as they’re pulling the tape out of the toilet is so pleasing! “I can’t believe I’m here again! I was so happy! Our guy did it! And now he’s about to mess up again and beat the hell out of this guy.”

It’s been extremely influential, much more than people realize. Have you seen Straight Outta Compton yet?

No, I’m going tonight.

Well, they copped one of your shots.

What did they get?

Skateland.

Really.

Yep. There’s a big track through the Skateland parking lot. You’ll recognize it immediately. But it’s not just that. There’s Empire. At some point, when they were getting the cast together, it had to come up in a meeting. “These are the Hustle & Flow people.”

One thing I’m still disappointed about—We were an MTV film. At the MTV movie awards, I always wonder why we didn’t get Best Kiss. I still think Terrance and Taraji’s kiss in Hustle & Flow is one of the best kisses ever. It’s soulful. They’re just devouring each other. That’s how people kiss, not this ‘movie kiss’ shit where they do a little light peck. You see tongues. Those mouths open up.

Shug and DJay’s kiss.

Have you had moments where you see it coming back at you from the culture in an unexpected direction?

I always like it when I see people make a play on the title. To my knowledge, I don’t think “hustle and flow” existed before I made it. I don’t know that anyone had ever put those two words together. Interestingly, it had a different title when I wrote it. It was originally called “Hook, Hustle, and Flow”. Then after a draft or two, I realized I was calling it Hustle & Flow, so I dropped the “hook.”

So Aldo’s pizza will do a poster with “hustle and dough”, the Memphis Roller Derby will have an event called “Hustle and Roll”. They all do the same poster design. I met Elijah Wood for coffee one day in Venice, and I walked right by a sign, “Hustle and Flow Fitness”. So I walk in there, and they’re like “Can we help you?” And said “No, I’m just the guy who made Hustle & Flow.” And they were like “Are you going to sue us?” And I was like, “No.” So they said “Here’s a free towel!” So I’ve got a towel with Hustle And Flow printed on it.

I was watching Run’s House, when Reverend Run had a reality show. And there was this one moment where he was talking to his son, and he said “You’ve got to get control over this. Remember when we were watching Hustle & Flow and he put his hands on the wheel and said ‘We in charge!’? Let me hear you say it.” I’ve heard that a couple of times.

Laura and I do it all the time.

It’s a sweet story, but I hope my mother will forgive me for telling it. It’s nothing bad against her. I had just proposed to Jodi to marry me. We were living together in my parent’s house in Northern California at the time. I had written a directed a play that was premiering, and Jodi didn’t show up. I wondered where she was. I saw my parents after the show, and they told me she was in a car accident that night. “She’s fine, a little shaken up, but we all decided it would be best to tell you after the premiere.”

So I go home and see Jodi, and she’s emotional. Her car is totaled. It was a head-on collision with this old guy who hit her. So I said, “Maybe you should have just told me.”

And she started to cry. “I didn’t know what to do. It was a big night for you. Your parents were saying we should wait to tell you until after the show. I just didn’t know what to do.”

So I took her hand, and said “Look, you’re gonna be my wife. You’re going to be making decisions for me when I’m not around, or if I can’t make the decisions. So if you’re uncomfortable with something, you need to speak up. You’re in charge.”

And she said, “I know, but…”

And I was like, “I need to hear you say it. Say I’m in charge.” And she said it. So it was like a thing between us. We’re going to be making decisions in our life. We’re in charge of each other.

‘We in charge.’

Are you the “Hustle & Flow Guy” in Hollywood?

Yes. And you know, it’s funny, because I feel like I’m part of a special club of directors. I don’t mind addressing this, because it’s a double-edged sword. John Singleton’s known for directing Boys In The Hood. There’s a lot of directors out there who, no matter what you do now, you’re still known for that first movie where everyone went “Wow!”

I was talking to someone the other day about Black Snake Moan. It’s the most confusing movie in my career. When it came out, nobody went to go see it. The reviews were polarizing. You either loved it or you hated it. I didn’t know what people were thinking. But now I’m older, and I realize that’s actually a good thing. You don’t want some humdrum movie.

But what’s confusing about it for me right now, is that a lot of people know it and love it. They don’t know how hard it was for me to deal with it after Hustle & Flow. That second movie, that sophomore effort, is something that is a formidable foe. It happens with every director who has a breakout success. That second movie, or that second season of a TV show, is being judged against magic that was lightning in a bottle. But I have to say, I’m still immensely proud of that movie.

Did I ever tell you the Piggly Wiggly story?

Tell it again.

It’s funny, because I just filmed the Marc Gasol video on this very spot. It’s Cash Saver now, but it used to be Piggly Wiggly. That’s where you when to go pay your late phone bill.

I think you can still do that there.

You had to wait in line right next to the doors. I was working at Barnes and Noble, and I got a phone call from a producer who was trying to get Hustle & Flow going. He said that Fox Searchlight really wanted to meet with me. They wanted to fly me out. I felt so excited. It was my favorite studio! I went running out onto the Barnes and Noble sales floor and cheered. “I’m going to Hollywood!” I worked in receiving, with the hardbacks and the calendars. I was back there all day with a boxcutter in a windowless, cement box unloading various tomes. I was so excited. Here I go! I wrote something, the studio responded to it, they said it was the most authentic thing they had ever read. I’m going to go meet with them about making it. Then three days later the meeting was cancelled. I was devastated. The producer told me they found out I was white, and they couldn’t bend their mind around that particular detail.

I’m older now, and I can kind of understand it better. Movies that are done at a certain budget, you need a hook to sell it on. You won’t have a movie star, so you sell the director. They couldn’t see why I would write a movie like this. And it was just because they found out I was white. They didn’t know me at all.

I was so depressed. The producer told me there was an African-American director out of USC that the studio was interested in, so maybe I should sell Hustle & Flow and they would have this director from USC direct it. So I agreed to do it.

Then, I was late on my phone bill, and I was standing in line at Piggly Wiggly. Below a certain economic line in Piggly Wiggly, we’re all equal. Black, Mexican, white, we’re all in line at Piggly Wiggly trying to pay our late bills. And there was this guy who looked at this long line, and looked at me, and said, “Man, this is some bullshit.” And there was something about that that just clicked with me, and I went off on this mental rant. Who are these people to tell me I can’t tell a story about my own city? I decided right then and there that I wasn’t going to sell the script. That was giving up more money than I had ever known at that time, and an additional two years of misery trying to get the movie made. I really felt whenever I was challenged on that particular thing—and I still get challenged on it, and I don’t think people are wrong to challenge me on it. I’ve been called a culture bandit, and racist, and misogynist. The one thing I do feel I was right about, and that other filmmakers like Spike Lee came to my defense about, is that I really wanted to be a regional filmmaker. I wanted to make a movie about Memphis, like I had done with The Poor And Hungry. And that’s what I held to. I live in Memphis, Tennessee, and we’re a very complicated city. Sometimes the things that people wish could be changed in our city, the bad things, actually produce really good art. That’s a story that’s been going on for decades.

Since W.C. Handy got banned by Boss Crump.

You’re getting all my Hustle & Flow stories. I’ll tell you the best compliment I ever got. I was at a screening in New York City with Chris Rock. He came out, and he was just so great to me. I’m a huge fan of his.

He said, “Man, when DJay goes into the strip club, and he’s arguing with Lexus, and she says ‘Man, I haven’t even made payout yet!’ I knew you knew your shit. I have heard so many strippers say ‘I have not made payout yet’. You just made a ghetto classic. Ten years from now, you will not be able to grow up in the projects without seeing Penitentiary, Shaft, and Hustle & Flow.”

Taraji P. Henson and DJ Qualls.

My 1995 movie was Friday, and I see a lot of influence from Friday to Hustle. I had never really thought about it in context of the 90s indie film revolution. But it’s absolutely Clerks.

Oh yeah. Seeing them go “Daaaaam!” That’s right out of Clerks. When I saw Top Five, that movie Chris Rock did just last year, I felt like I was watching 90s indie cinema. It had been a long time since I saw that. We’re gonna get all our friends together and make something fun, something out of the box. The lo-fi elements are some of the things you really dig about it.

Ice Cube was able to get more money together, because he’s been successful in music at that point. But what he was doing was not significantly different than what we were doing five years later. So here we are, fifteen years into the digital revolution, and you came out of that scene. What do you think about now, looking back? What do you think about the whole “indie film project”?

I am sad, because the further I get away from it, the more I realize that it was a unique time in culture. I don’t see the same energy or interest in the younger generation, meaning 15 year olds. They’re not running out to see Slacker because they read about it in a magazine. Or Down By Law, or Woman Under The Influence. The flip side to it, is that they can watch it on Netflix now, but they can also get a phone call in the middle of that Netflix viewing. They’re not getting the same experience. There’s that bitter part of me that’s thinking. I’m turning into that greying, cantankerous older man who’s saying “Oh, it was so different back in the day.” I do look with a great deal of optimism towards independent expression in this generation that we didn’t have. It’s just going to morph into something else.

But a good movie still works with a young mind. I walked into my daughter’s room, and she and my son were watching Mad Max: Fury Road. Now, she’s seven years old, and a lot of people think that movie is not appropriate for a seven year old girl. But she was hitting me with all these questions: “Why is it all desert? Why is there no water? Why is there no gasoline? Why are they fighting over it?” I explained what a post-apocalyptic movie was, and compared it to Hunger Games. Then she turned to me, and her expression was just priceless. She said “This is the greatest movie I’ve ever seen!”

I remember that feeling, of seeing something different, of being inspired. My son and my daughter, after watching that movie, were saying “We’ve got to make movies.” They were just so solid on it. People like Mike McCarthy, Morgan Jon Fox, Kentucker Audley, Chris McCoy, and Laura Jean…we were all of this time. We were inspired by independent cinema, and we wanted to be a part of the movement. It didn’t require success. You didn’t have to sell your movie at Sundance. You wanted to be an independent filmmaker, and you struggled and went into debt to become one. Nowadays, a whole movie can be made, cut, and uploaded on your iPhone. The way that things can get out there, it’s so easy. I still wonder, though, is the craft of cinema being exalted, or is its growth being stunted by technology?

I think it’s being pushed in different directions. Back then, all of us, at the same time, gained access to technology that allowed us to do what we’d been trying to do since we were teenagers. So what we did was, we took that technology and applied to towards creating inside this paradigm—feature films—that we were familiar with. But that’s a paradigm that evolved from a very different technological situation. It was hard to make moving images, so you had to gather all these resources together, and once you made it, then you got a whole bunch of people into a room to watch this big presentation.

But now, these kids…and I see it all the time with the Black Lodge tribe, for example. They’re very inspired by the movie image, and they want to make it, and they understand it, but they’re not constrained by two hours sitting in a movie theater. They don’t have to do that to get an audience to watch their movies.

But now, I spend a lot more time in theaters than I used to, because of this job. I like being in a movie theater with people. Even if they’re annoying.

Me too.

I wouldn’t want to sit here for ten hours and watch Game Of Thrones with them. I just had a good audience experience watching American Ultra. It was like we were seeing something cool that everyone else was overlooking. I had a great audience experience watching Straight Outta Compton. When Easy-E died, I thought people were laughing. But I looked behind me, and there were these two big black guys who were sobbing because they were so moved by that moment.

Now you’ve got me waxing philosophical.

That’s what I do.

Taryn Manning as Nola

Do you know where the first screening of Hustle & Flow was, ever?

Muvico Downtown?

No. The First Congo theater!

You showed it at the [Digital Media] Co-Op?

I can’t believe I’m telling you this. I would have gotten into so much trouble if something went wrong. It was around November, 2004. We had just locked the edit. We were going to show it around Hollywood to people before Sundance. There was no music edit, no color timing, nothing. I was going home from California to Memphis for a week. So I told my editor that I wanted to take a copy home with me. And he was like, look. Soul Plane with Snoop had just been bootlegged. It was everywhere on the street. And it completely killed that movie at the box office. Everybody that was going to see that movie had a DVD already. Piracy was a huge problem.

So my editor, and I hope I don’t get him in trouble, he gave me the movie in two parts on two DVDs. So I took those two DVDs to my little editing suite back in Memphis and stitched them together in Adobe Premiere, and dumped it off to tape. I called up Morgan [Jon Fox], and said I want to have an underground screening. Literally underground. You’d go down the stairs at the First Congo church, and the theater was in the basement. I showed Hustle & Flow to about 70 people to the first time. It was special. There were some people who were going, “I don’t think this is going to work…”, and people who loved it. I remember Morgan being a big supporter of it. But there was a moment where I was talking to everybody, and went over to my digital deck to get the tape, and it wasn’t there! I freaked out. But it turned out that Morgan had taken the tape out, because he knew I was so freaked out about the piracy. But boy did I fucking freak out. That would have been a tragedy.

Holy shit. Well, it all worked out for you. I’m glad you’re working on Urban Cowboy and Empire.

I just watched the cut of the episode I did for Empire. It’s so good. I’m so pleased with it. You gotta remember, I’m a big fan of the show, regardless of Terrance and Taraji. I’m just into it. And I got to make one! It’s fun.

With that and Urban Cowboy, it’s a lot more material on your plate than a feature film, right?

I’ve got other feature films and TV shows I’m working on, but right now I’m just trying to stay focused on Urban Cowboy.

That’s what I’ve learned, working with you. You gotta keep a whole bunch of balls in the air at once in the hope that one of them goes somewhere.

Oh yeah. When I was working on Empire, Attica Locke, who wrote the episode, was hearing about all the projects I had going. She said, “How do you have all those jobs? You’ve got like eight projects!”

And I said, “I don’t have eight jobs. I have eight hustles.”

Throwback August: Hustle & Flow