Nearly 150 people, mostly clad in black suits and dresses, are gathered on the lawn of the Woodruff-Fontaine House on a chilly All Saints’ Day evening. They’ve come to pay their respects to Memphis and Shelby County Film and Television commissioner Linn Sitler, who’s lying in a casket in front of the century-old mansion.

Of course, Sitler isn’t actually dead. She’s just pretending. And as her friends — U of M dean Richard Ranta, filmmaker Mike McCarthy, and NARAS head Jon Hornyak — deliver faux eulogies, they’re also raising funds to breathe new life into the Victorian Village neighborhood.

The “Night at the Village” fund-raiser, which also featured a requiem choral evensong at St. Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral on Poplar and a bagpipe procession down Orleans Avenue, raised $3,400 for the Victorian Village Community Development Corporation (CDC).

That money, along with a combination of public and private funds, will go toward the CDC’s plan to revive what was once the city’s most upscale neighborhood. At the turn of the century, Italianate Victorian and Second Empire mansions lined Adams Avenue, but the city’s “urban renewal” project of the 1960s razed most of those structures. Now only a handful of historic homes are left in Victorian Village, and the CDC plans to use them as a springboard for new development.

“Between the Victorian Village’s boundaries — Danny Thomas, Poplar, Manassas, and Madison — there are 25 structures on the National Historic Register. This is the only concentration of historic architecture from that century in the city,” says Scott Blake, the executive director of the CDC and a longtime resident of the neighborhood. “The way to support those historic assets is to build a residential neighborhood around them.”

Since the village falls in the Center City Commission’s central business improvement district, the agency commissioned a redevelopment study by Looney Ricks Kiss Architects in 2004. The resulting plan calls for single and multi-family housing built in a style to complement the existing Victorian-era structures. It also suggests improvements to the two city parks in the area, sprucing up existing apartments and businesses, and connecting the museum houses with a green boulevard for walking tourists.

Though the plan was developed four years ago, it is finally gaining momentum, with the first few homes now built along Jefferson. The city also hopes to reopen the Mallory-Neely and Magevney museum houses, and millions of dollars in improvements to the adjacent medical district are well underway.

“We want places for the doctors and staff of the medical district to live in the area, and we’re looking for housing that runs the price spectrum,” says Beth Flanagan, director of the Memphis Medical Center. “Victorian Village will be such a gem for the Medical Center.”

Millionaires Row

In 1845, a pair of brothers from New Jersey traveled to Memphis to expand their carriage-building business. Though one brother returned to the Garden State, Amos Woodruff decided to stay put. He became head of the Memphis City Council, and president of two banks and owned a railroad company, a hotel company, an insurance company, a cotton business, and a lumber firm.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Gate detail

By 1870, Woodruff’s rise to prominence had earned him the money to build a magnificent house at 680 Adams Avenue, which was then considered the outskirts of the city.

“He told his wife if she’d come down from New Jersey to live in Memphis, he’d build her a really nice house,” says historian Jeanne Crawford, a docent at the Woodruff-Fontaine House. “From looking at tax records, we’ve determined that it cost him $40,000 to build this house. You couldn’t build a garage for that now.”

Woodruff’s home, now open for daily tours as the Woodruff-Fontaine House, became one of many ornate mansions along Adams, known as Millionaires Row. Wealthy cotton merchants and the city’s most elite families lived in the neighborhood.

“Their entertainment was very neighbor-oriented. They played bridge with one another and poker. And when they had a bash, it was a real bash,” Crawford says. “I’m sure it was a charming time for those with money.”

But as the city grew, many of the families eventually migrated east to newer neighborhoods such as Central Gardens. By the 1950s, many of the mansions sat empty. Others had been converted into tenement housing.

“It was kind of seamy. There were lots of winos living in these houses, and my house was in shambles,” says Eldridge Wright, the neighborhood’s longest surviving resident, who lives in a grand 1880 home across from the Mallory-Neely House. “It was not a very attractive neighborhood back then. But to me, even the houses that were dilapidated had great charm.”

Wright moved into the neighborhood in 1955, first occupying a brick carriage house that once sat behind his family’s Victorian home on Jefferson. The main home was razed by the city in the mid-’60s, when Jefferson was widened. Its destruction was part of a massive urban renewal project that demolished most of the Victorian homes in the area.

Wright moved to his house on Adams shortly after his family’s main home was razed. But he wasn’t about to stand back and watch the city destroy the entire neighborhood.

“We formed a group to try and save some of the homes. They had plans to demolish the Fontaine House and Mallory-Neely House, and we were able to stop that,” says Wright, who is lovingly referred to the “Mayor of Victorian Village” by current residents. “At the time, I’d rather have been drawn and quartered than give a speech in front of the City Council, but I knew that I had to make a point to save these places.

“I appealed to Mayor Henry Loeb that this place could be such a nice tourist attraction if Memphis would save these homes. That idea appealed to him, and I think it was on that basis that we were finally able to preserve a few of them,” Wright says.

Thanks to Wright’s efforts, a few remnants of the lavish Victorian era in Memphis remain. The Woodruff-Fontaine House, now under city ownership but leased by the Association for the Preservation of Tennessee Antiquities (APTA), is now the only home open to the public.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Jeanne Crawford

The other city-owned museums — the Mallory-Neely House at 652 Adams and the Magevny House at 198 Adams — were open for tours until 2005 when they were temporarily closed due to city budget cuts.

Operated under the city-funded Pink Palace Museum system, the homes originally were slated to reopen this year. But Pink Palace officials still are working on a funding plan, which should be complete by the end of the city’s fiscal year.

The James Lee House, an 1848 mansion next door to the Woodruff-Fontaine House, sits empty, its dark and gloomy windows reflecting Orleans and Adams avenues. Though it’s managed by the APTA, the nonprofit preservation group doesn’t have the funds to renovate and open it for tours.

“We’re in the middle of a proposition for the CCC to put [the James Lee House] out for public bid for renovation and restoration,” Blake says. “A private entity, whether it’s one of the hospitals wishing to use it as office space or just someone who would like to open a bed and breakfast, would actually purchase the house and do the restoration according to strict standards.”

Across from the Woodruff-Fontaine House, restaurateur Karen Carrier’s successful Mollie Fontaine Lounge operates in an 1886 home that was built as a wedding gift for Mollie Fontaine Taylor, whose family occupied the Woodruff-Fontaine House after the Woodruffs moved out.

The lively tapas lounge at 679 Adams was Carrier’s first home in Memphis after relocating here from New York in 1985. She still runs her catering business, Another Roadside Attraction, in the carriage house behind Mollie’s. Carrier first converted the home into Cielo, a white-tablecloth French restaurant, in 1996, when she moved her family to East Memphis. Cielo got a hip, new facelift last year when it became Mollie’s.

“At Mollie’s you can take in the ornate architecture,” Carrier says. “You don’t have a tour guide telling you where to go. You can sit down, look around, and really take it all in.”

Some of the other historic structures, like the Lowenstein Mansion and the Pillow-McIntyre House, are privately owned and used as residences or law firms. But thanks to the urban renewal era, the neighborhood also is peppered with unattractive apartment complexes, warehouses, and industrial buildings from the 1960s.

Rising from the Ashes

Jocelyn and James Henderson consider themselves pioneers. The couple, an attorney and Memphis policeman, respectively, relocated from Harbor Town to a new town home on Jefferson in June.

“We can shape the Victorian Village neighborhood,” says Jocelyn, seated at a breakfast nook in her modern kitchen. “We can mold it into a safe neighborhood where my son Jordan can play outside.”

The Hendersons’ home is one of three new town houses adjacent to Blake’s two historic homes — built in 1863 and 1867 — at the corner of Jefferson and Orleans. Blake, who runs a company that provides design resources for museum exhibitions and the performing arts, designed the new houses.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Eldridge Wright

The single-family homes, built in a style that complements the nearby Victorian architecture, are models for the future in-fill housing called for in the Victorian Village redevelopment plan. But Blake says there’s room in the neighborhood for multi-family housing as well.

“It’d be great if families came in and tried to build Victorian mansions, but that’s not likely,” Blake says. “But someone could build a six-unit condominium that looks like a Victorian mansion. You could even do mansion-style office buildings, especially considering how close we are to the Medical Center.”

As for Jocelyn Henderson, she loves being able to walk downtown from her home, and some days, when she’s scheduled to work at the Shelby County Juvenile Court, she can walk across the street to the courthouse on Adams. But she says a few things are missing from the neighborhood — namely, a small grocery store, a coffeehouse, and a bigger selection of restaurants.

The Victorian Village redevelopment plan calls for more mom-and-pop retail shops, restaurants, and other amenities. Currently, ICB’s Discount Store is the village’s only retail market, and there are just a few neighborhood restaurants, like Neely’s Barbecue and Mollie Fontaine Lounge.

When Carrier lived in the neighborhood in the mid-1980s, she remembers the area being a tourist hotspot, since all three museum homes were open to the public.

“There were so many tourists, they would tour the museums and then come knock on my door, thinking my house was open to the public too,” Carrier says.

After the city closed two of the museums, the tourist crowds faded. But with plans to reopen the Mallory-Neely and Magevney homes, there’s talk of building a green boulevard or park that would connect the museum houses on Adams to Jefferson.

“To make the neighborhood walkable, you have to have cross streets and not just the long blocks that we now have running east to west,” Blake says. “We need to make some short streets that run north and south, and we’d like to do them with a green median.”

Not much can be done with unattractive existing structures, like the Shelby County maintenance facilities, the Crime Victims Center, and the Memphis Fire Department maintenance facilities.

“If those were to become available for reuse at some point, we’d have to look at which ones would be worth keeping and which ones could have something else built in their place,” says Steve Auterman, the master plan’s designer from Looney Ricks Kiss.

Auterman says the group is working with owners of some of the dated apartment buildings in the neighborhood, like the 312-unit Edison high-rise on Jefferson.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Jocelyn and James Henderson

“They may decide to improve the structure that’s already there or take part of it down and replace it with more desirable apartments,” Auterman says.

Pest Control

There are two parks in Victorian Village — Morris Park on Poplar and Victorian Village Park on Adams. Victorian Village Park is a mostly empty green space dotted with a few park benches, which typically double as beds for the homeless. Morris Park’s only draw is a public basketball court, but most residents are afraid to use it.

“Morris Park is a little scary,” Blake says. “There’s drug dealing and prostitution in the park, and it’s not welcoming to the community.”

The city parks department is working with the Victorian Village CDC on a plan for enhancing the parks and making them safer.

“But to deal with the park, you have to deal with the area around it,” Blake says. “Every building that faces Morris Park, like the Memphis Housing Authority offices and Collins Chapel, needs to develop a program where there’s 24-hour observation in the park. We may even build some townhouse apartments that look over it. When you have a presence like that, it sends the roaches scuttling.”

Homeless people from the nearby Union Mission on Poplar often find their way into the village, creating the perception that the area is unsafe. Though violent crime isn’t typically a problem, burglaries persist.

Since the Hendersons moved in this summer, they’ve had two car break-ins.

“James was parking his car on Jefferson, and three weeks ago, someone busted out his windows,” Jocelyn says. “They also tried to break into my mom’s car, which was parked on Jefferson, a couple days later.”

A check of Memphis Police crime statistics from the past 30 days reveals 21 thefts from vehicles in a half-mile radius of Adams and Orleans. There were seven residential burglaries and two business burglaries reported during that same time.

But Carrier says the break-ins along Adams Avenue have dropped since she hired security for Mollie’s.

“When I had Cielo, there was a big crime problem. People would be all dressed up and they’d walk to their cars and their windows would be smashed,” Carrier says. “But from day one at Mollie’s, we’ve had security from the time we open until we close at 3 a.m. We haven’t had any more trouble.”

Blake says most of the vagrants likely enter from the village’s northern border along Poplar Avenue. The plan calls for some much-needed sprucing up in that area with high-density rental and condo units built in a style similar to the apartment buildings from the 1920s across from Overton Park in Midtown.

“Right now, that area is homeless shelters and trashy pawn shops and the back side of Juvenile Court. So you need a good imagination to picture what it might look like,” Blake says. “Poplar is our front door to downtown, and right now, it’s like Whack-a-Mole with all the people hanging out in the street.”

Though it may be hard to control the homeless population, the county’s planning to build a 30,000-square-foot forensic center along Poplar in the Juvenile Court parking lot. Because of the nature of the operation, the building will require security and that may curb some of the crime.

There’s no set timeline for the Victorian Village redevelopment plan, and funding will come from a variety of sources. Victorian Village recently was selected as a Preserve America Community through a White House initiative that recognizes communities that are using their historic assets for economic development and community revitalization. The designation makes Victorian Village eligible for certain federal grants.

New commercial businesses and multi-family rental developments may also be eligible for PILOT tax freezes through the CCC.

For now, Blake is happy to see a few new residents and increased enthusiasm in the neighborhood.

“Part of our mission is to raise awareness, and it’s great to see people taking an interest,” Blake says. “For so long, this place was just languished and forgotten.”

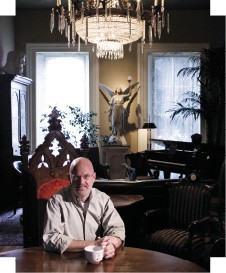

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Scott Blake

United Housing/Facebook

United Housing/Facebook

United Housing/Facebook

United Housing/Facebook  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks