Billy Corben’s documentary Cocaine Cowboys was a minor hit when it was released in 2006, but it has proven hugely influential in the current golden age of documentaries. It ostensibly told the story of the motley crew of renegades, McGyver types, and hardened criminals who pioneered modern drug smuggling, but it was really about a specific place and time: South Florida in 1970s and ’80s.

Corben’s influence is felt profoundly in Gabe Polsky’s Red Army. Like Corben’s work, it focuses on first person interviews with a fascinating cast of characters to sketch the outlines of a bigger story. During the Cold War, life inside the Soviet Union was only known to Americans through propaganda. Soviet propaganda painted a picture of a worker’s paradise, free from want and capitalist exploitation of workers. American propaganda, on the other hand, highlighted the political subjugation of the Russians and their conquered peoples and the failure of communism to provide the most basic goods and services.

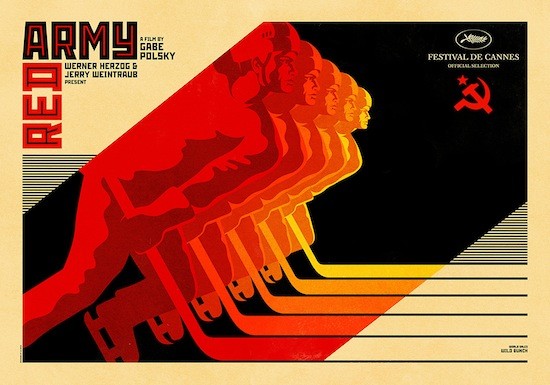

Red Army

The picture painted of life behind the Iron Curtain in Red Army is somewhere in between the two extremes. Polsky’s subject is the story of the most popular athletes in the Soviet Union, the national hockey team, who dominated the sport for decades. The star of the show is Slava Fetisov, who is introduced taking an important phone call while he is being interviewed by the impatient Polsky. Fetisov’s list of accomplishments and accolades spills off the screen, in one of the great little visual touches Polsky brings to the film. He is probably the greatest defensive player the game has ever seen, and the story of how he got that way is the story of the Soviet system in a nutshell. He was born in the Soviet Union that, in 1958, was still reeling from the destruction of World War II. Even though he grew up in a 400-square-foot apartment inhabited by three families, he describes himself as a happy child, because he got to play hockey. At the age of 8, his burgeoning talent was recognized by Anatoli Tarasov, the coach who built the Russian Army team from scratch after the war and created an international sports power.

The training regime for the players was brutal. 11 months out of the year, the team lived in virtual isolation. Next door to the hockey camp was the chess players’ camp, and as legendary player Anatoly Karpov recalls, the two, very different kinds of players influenced each other. Tarasov created a whole new strategic philosophy that emphasized teamwork and deep strategy and revolutionized hockey, soundly defeating the international champion Canadian team in 1979. But Tarasov had the misfortune of running afoul of Leonid Brezhnev, and he was replaced by one of the Soviet premiere’s KGB cronies before the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. The resulting upset by the American hockey team, dubbed The Miracle On Ice in Western media, stunned Russia and redoubled the resolve of the players, who would then continue to dominate the sport through the next decade. In one especially telling archival clip, a young Wayne Gretzky, after losing handily to the legendary Russian Five, says “We can’t compete. It’s too difficult.”

Polsky gives just as much time to the dissolution of the legendary team as he does it rise, and it serves as a proxy story for the end of the Cold War. Tired of the deprivations of Siberia and lured by promises of wealth in the West, the team slowly fragments and its players absorbed into the NHL. But the story doesn’t stop there. Polsky continues to trace the players as they navigate the oligarchical world of Putin’s Russia.

The director’s light touch allows unplanned moments to seep into the film, such as when a former KGB agent has trouble controlling his feisty granddaughter while trying to tell a story about the old Soviet system. I’m not much of a sportsman, much less a hockey fan, but this meticulously crafted documentary is a knockout.