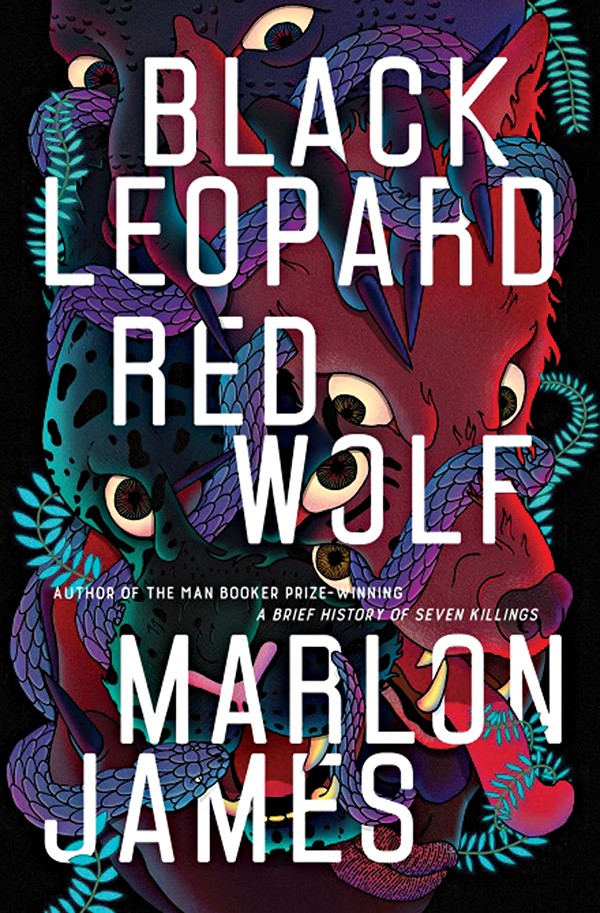

“The child is dead. There is nothing left to know.” So begins Black Leopard, Red Wolf (Riverhead Books), the fourth novel by Marlon James, the Jamaican author who won the Man Booker Prize in 2015 for his A Brief History of Seven Killings. The speaker is Tracker, Black Leopard‘s narrator, a mercenary with a nose, known for his ability to track anyone anywhere, once he has their scent. Tracker’s gift lands him a deceptively simple job when the Moon Witch Sogolon needs to find a missing child, a boy without a name but not lacking in importance.

Working for a third party, Sogolon assembles a fellowship to locate and return the stolen boy. At the outset, their ever-shifting party includes the wolf-eyed, keen-nosed mercenary Tracker; Leopard, a shapeshifting jungle cat; and Sadogo, a melancholy giant. And though Sogolon’s fellowship is strange, still stranger things await them.

Hallucinogenic and magical, the pages of Black Leopard, the first novel in a proposed trilogy, are populated by witches, monsters, and fantastical beasts. There’s the flesheater, Asanbonsam, and his brother, the bat-like, blood-sucking Sasabonsam. And Ipundulu, the vampiric lightning bird, whose victims — those who live — become his slaves, beguiled by his charge. And every person Tracker meets could be a shapeshifter, a man-eating lion or hyena taking the form of a human. Tracker’s all-powerful nose becomes invaluable in James’ land of shifting allegiances and layered narratives.

Tracker comes from one of the river tribes, though he claims no home and no family. He is a lover of men in a world where it is dangerous to be so, and a nonbeliever in a world of dozens of religions. “I don’t believe in belief,” Tracker says again and again. And the question is, how could he afford the luxury of certainty, in a world so defined by its history, but a history always partially obscured? In James’ novel, history is a black hole, invisible, hidden, but with an inescapable gravitational pull, warping reality around itself.

The wolf-eyed mercenary is a trickster detective — and a fitting narrator for James’ tale of a missing boy, a hidden history, and an uneasy fellowship. For truth, as much as the child, is what’s missing in the world of Black Leopard, Red Wolf. The story takes place at a turning point in a mythical Africa, infinitely diverse and complex, with many cultures represented, each with its own values and beliefs. It’s the end of the age of the oral historians, who sang the history of the land, and though glyphs are old news, it is the beginning of the time of phonetic writing. James has created a world whose history is informed by our own, even while it underscores the changing ways we look at truth in our digital age.

In an interview with The New Yorker, James said he studied African folklore and mythology, in its myriads forms, for two years before beginning the novel, and his research shows on every page. The world of Black Leopard is made up of dozens of interlocking and often conflicting narratives.

With both the novel’s prose and plot, James confronts the whitewashing of history — and of the fantasy and science-fiction genres, specifically. Much of the novel’s intrigue revolves around the co-opting of history by the Spider King Kwash Dawa’s royal ancestor, who, in a violent coup, not only departed from his peoples’ traditions, but erased them. He had the storytellers killed, and within a few generations, history was what the king said. Or at least, that’s what Tracker has been told.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf asks its readers to confront their beliefs, as with every discovery, Tracker calls into question what he has been told so far — and what he has deigned to pass on to the reader. And with intrigue that deep, there’s nothing left to do but cozy up and enjoy the mystery. Because the truth is, in James’ novel as in life, we may never know the whole truth.