The final meeting of the version of the county commission that was elected four years ago began on Monday with a show of harmony, with mutual compliments, and some last commemorative poetry by limerick-writing Commissioner Steve Mulroy, and expired with a last sputter of disputation. In between, it advanced on two fronts and retreated on another.

Though it might not have appeared so to those unversed in the habits and ways of the county legislative body, this culminating session of the Class of 2010 also offered a symbolic forecast of better times ahead economically. It was during the heyday of the housing boom that went bust in the late aughts — leaving the county, the state, and the nation in financial doldrums — that ace zoning lawyers Ron Harkavy and Homer “Scrappy” Brannan were omnipresent figures in the Vasco Smith County Administration Building.

It seemed like years, and probably was, when the two of them had last appeared at the same commission meeting, each serving as attorneys for clients seeking commissioners’ approval for ambitious building plans. But there they were on Monday, reprising their joint presence at last week’s committee meetings — Harkavy representing the Belz Investment Company on behalf of a new residential development in southeast Shelby County; Brannan representing the Bank of Bartlett in upholding another development further north.

Both were successful, and it was a reminder of old times — say, the early 2000s, when the building boom so dominated commission meetings that worried commissioners actually had to propose a moratorium to slow down the proliferation of sprawl.

The matter of residence was, in yet another way, a major focus of Monday’s meeting, in its overwhelming approval of a resolution on residency requirements for commission members proposed by Mulroy, a Democrat and the body’s leading liberal, and amended by Republican Commissioners Heidi Shafer and Terry Roland. The commission thereby wrote the final chapter of the Henri Brooks saga and set precedents for the future.

The resolution, which provides a checklist of items to satisfy the county charter’s existing residency requirements, was strongly resisted by senior Democrat Walter Bailey, who had been the commission’s major defender of Brooks in her successful effort to stave off legal eviction from the commission after the apparent discovery that she no longer lived in the district she was elected to serve.

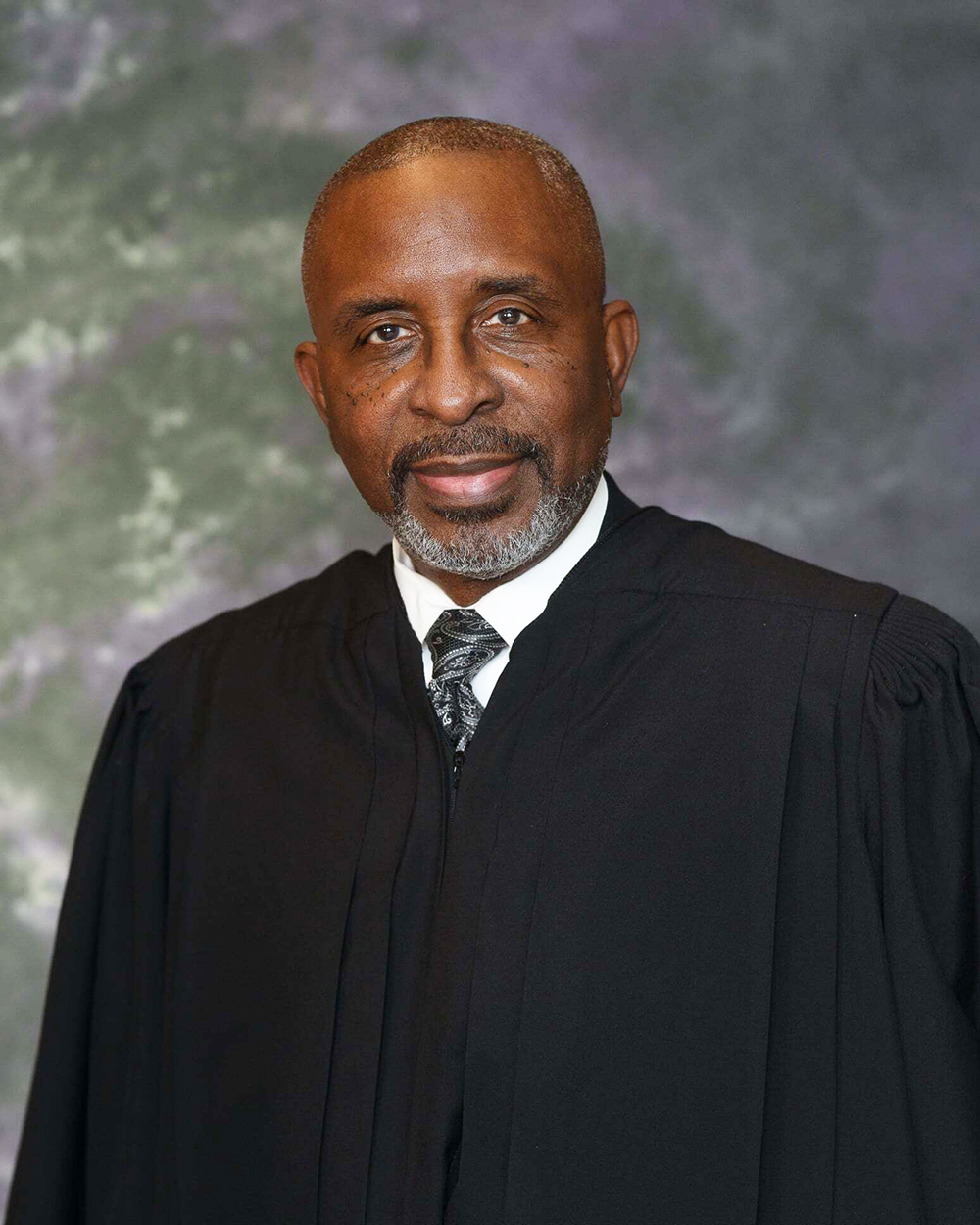

Bailey, who has called the Brooks affair a “witch hunt,” has continued to maintain that the commission has no authority to impose or enforce such rules, citing a decision last month by Chancellor Kenny Armstrong upholding Brooks’ appeal of a finding by County Attorney Marcy Ingram that vacated Brooks’ seat in conformity with the county charter. Other commissioners pointed out that Armstrong had actually ruled that it was the commission, rather than the county attorney, that could decide on the matter, thereby affirming the body’s authority.

In any case, Bailey said the commission should operate on the principle of “good faith” and not pursue vendettas. He was backed up in that by Commissioner Sidney Chism, who went so far as to suggest that his colleagues were out to “kill” Brooks.

Most commissioners, though, clearly felt such thinking was over-protective and counter not only to the county charter but to the same traditions of residency enforcement that governs the placement of school children and the right to vote in a given precinct.

Moreover, they had just as clearly soured on Brooks. Commissioner Mark Billingsley said his constituents had concluded that some members of the commission were “not trustworthy.” And according to Mike Ritz, Brooks had “cheated” her constituents by not attending any commission meetings since her attorneys had managed to ensure that she could remain on the body until the end of her term this month. “She’s been cheating them for years,” he added. Shafer said pointedly that the rules up for adoption were meant to prevent efforts “to defraud the voters.”

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Back on the scene Monday were zoning lawyers Ron Harkavy (top, with Commissioner Heidi Shafer), and “Scrappy” Branan (bottom, left, with Bank of Bartlett president Harold Byrd and Commissioner Terry Roland);

Essentially, the amended resolution provided 10 different items to determine a challenged commissioner’s residency — ranging from utility bills to drivers licenses to documents certifying public assistance or government benefits — and required that only three of them be produced. The resolution passed 8-to-3, though it was understood that it might be met down the line with court challenges.

The commission took another important concrete step in approving a third and final reading of an ordinance proposed by Commissioner Ritz raising the pay of Shelby County Schools board members to $15,000, with the board chairman to receive $16,000. Though that amount was roughly only half the compensation received by county commission members and should be regarded as a “stipend” rather than a salary, it was still a three-fold increase for school board members.

In evident agreement with Ritz that such an increase was overdue, particularly in a “post-controversy” (meaning post-merger) environment, the commission approved the ordinance by the lopsided margin of 10-to-1.

But if comity was to be had in most ways Monday, it fell short on the last item of the day — and of this commission’s tenure. Despite the presence of numerous citizens and clergy members testifying on its behalf, a resolution co-sponsored by Mulroy and Bailey “amending and clarifying the personnel policy of Shelby County regarding nondiscrimination,” fell short by one vote of the seven votes required for passage.

The same resolution, which specifically added language safeguarding county government employment rights for gay and transgendered persons, had been given preliminary approval by the commission’s general government committee last week. A highlight of the often tempestuous debate on Monday was an angry exchange between Democrat Chism, a supporter of the resolution, and Millington Republican Roland, who opposed it.

The specific language of the resolution was needed in the same way that specific language had been needed in civil rights legislation to end discrimination against blacks, said Chism, an African American. Discrimination, said Chism, “happened to me all of my life. Nobody saw it until the law changed.” Roland shouted back that the resolution was but the vanguard of a homosexual agenda. “It’s an agenda!” he repeated.

In the aftermath of the resolution’s near-miss, a disappointed Mulroy, who had authored the original nondiscrimination resolution of 2009, noted that Brooks, had she been there, would likely have been the necessary seventh vote, and that Chairman James Harvey, who abstained from voting, had proclaimed on multiple occasions, in front of numerous witnesses, that the resolution should be passed but that he, Harvey, who aspires to run for Memphis mayor next year, might have to abstain for “political” reasons.

Another term-limited commissioner, Ritz, may be a principal in the city election, as well. The former commission chairman, who has moved from Germantown into Memphis, said he is eying a possible Memphis City Council race. There is, it would seem, life after county commission service.

Memphis Police Department/Facebook

Memphis Police Department/Facebook  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker