Since the novel coronavirus pandemic came to the Memphis area, more than 18,000 people have come down with COVID-19. As of this writing, 259 people have died. Four months after a state of emergency was declared, the numbers continue to tick upwards with no end in sight.

The Flyer spoke with survivors who volunteered to tell their stories. These people have experienced a disease that simply didn’t exist in humans a year ago. Several common themes emerged. Most strikingly, everyone we spoke with appears to have lasting effects from their brush with the virus. Here are five stories of fear and strength in the face of the unknown.

Mike Maple

Mike Maple

Jeff “Bunny” Dutton

Jeff “Bunny” Dutton is a musician and recording engineer. His partner Suzy Hendrix is a visual artist who specializes in stained glass. Dutton’s first symptoms appeared in early March, when he was working in the studio. “I remember setting up mics for recording, and all of the large muscles in my body were aching like I was lifting cars the day before.”

After a successful weekend in the studio, Dutton and his friends went out for drinks.

“It was a Sunday, and a large group was at a Mexican restaurant,” he says. “We were all planning on this being our last night out together till the danger was over. We were pretty naive about the whole thing at the time, and didn’t think it was going to turn into a major pandemic. I was very uncomfortable. My legs were still aching and I felt restless and confused. My head was getting cloudy and I was starting to get anxious about it. I couldn’t concentrate on anything.”

The next day, Dutton couldn’t get out of bed. By mid-week, he was having trouble breathing. On Friday, March 17th, he finally went to a minor medical clinic. “They said that my lungs sounded fine and they couldn’t understand why I was in so much distress, so they gave me a COVID test just to be safe. The nurse asked me if I wanted to go to the hospital for chest X-rays. I told her I couldn’t stay on my feet any longer, and I went back home to bed. I do remember they gave me a steaming treatment that is used for asthmatics, but it did no good.

“About this time Suzy started feeling ill. Three days later my test results came back positive and Suzy went for tests. For some reason, hers was negative, and though she wasn’t nearly as sick as I was, it still wasn’t any fun.”

Dutton and Hendrix were among the first people in Memphis to experience the full course of COVID-19. “I had one night of fever and demented dreams, but for the next couple of weeks I just laid around trying to get an entire lung full of air into me,” Dutton says. “No one knew what to do or what to expect, so I had to self medicate. I chose to use aspirin, despite the crazy warnings on the internet. Later, I started finding out about all of the blood clotting doctors were finding, so I was happy with that decision. As far as spending a couple of weeks gasping for breath goes, it is the worst. I suggest practicing some sort of meditation now. You might need it someday when all you can think about for days at a time is, ‘Don’t stop breathing.’”

With both people in the household sick, the couple turned to their community for help. “What was really great about the whole thing was friends dropping off fresh food, books, and cake, and relatives depositing cash into the bank account. Such a helpful happy bunch, you gotta love ’em.”

But navigating the health-care system and government aid programs while fighting for breath was a traumatic experience. “I’m happy that I did not need hospitalization,” Dutton says. “Tennessee is a crappy state to live in if you need medical care.”

Eventually, Dutton found he had a little more energy every morning. “I’m pretty good for five or six hours now. … Being sick was pure hell. I’m glad to be back up and about, but I have some pretty serious damage. Unless I get hit by a bus or something, one good lung infection is all it’s going to take to take me out. My days of being a social animal are probably over.”

His experience has left one enduring question. “I have no idea how I contracted the virus,” says Dutton. “Almost everyone I know was traveling around the country, or on their way back from Mardi Gras at that time. Other than Suzy, none of my friends seemed to get sick. It’s a mystery.”

Leslie K. Nelson

In late May, Leslie K. Nelson had a houseguest for a few days. On June 1st, the guest was treated for what doctors believed was heatstroke. It was COVID-19. “Around the 7th or 8th, I too was sick,” Nelson says. “But I was much worse than my friend.”

Nelson’s guest had 10 days of mild symptoms. Nelson was admitted to the hospital on June 11th.

“I called because I couldn’t breathe,” she says. “I was coughing, constant migraine, hot, sweaty, hurting all over. I could not focus at all. I was immediately admitted.”

Nelson was given oxygen and intravenous fluids in the hospital. Everyone entering her room was required to wear protective gear. “I only saw a doctor the first couple days. I had questions. The nurses would tell me to bring that up with the doctor. I did request to see him a few times. My questions and concerns went unanswered. Honestly, I know they’re busy, I know they’re understaffed, I know they’re overworked. But I was made to feel like I was bothering them.”

Nelson says the headaches were constant, accompanied by mental confusion, the “CoFog.” She found herself unable to do even basic tasks for herself. “The weakness is a different type of fatigue than I’ve ever experienced.”

After eight days, Nelson was sent home in an ambulance. She was still so weak she had to be strapped into a gurney for the journey. “They told me there were patients in the emergency room that needed my room. They sent me home even though I couldn’t take care of myself.”

Nelson says her friends and family have rallied around her. “They’ve picked up my medications, brought me groceries — because, remember, I can’t go out. Even if I could, I don’t have the energy or brain power yet. One friend brought me the Huey’s veggie burger I had been craving. A neighbor and close friend made it a point to get my mail out of the mailbox and drop off at my door because I’ve been too weak to go to the mailbox. Then there have been the homemade soups and chocolates. I couldn’t have survived without my friends.”

Today, Nelson is still feeling the effects of the virus. She is one of the people known in medical circles as “long haulers.” Her fever never went away, and no period of recovery has proven to be permanent. “Symptoms develop at different times, even new ones, like tendinitis and ringing in my ears/head,” She says. “My taste never totally went away. It changed, got weird. Some things got really awful. Chocolate tasted like oil.”

Nelson decided to document her experiences on Facebook with a series of posts called “My No Pity Covid-19 Symptoms.”

“I was starting to feel pretty down, discouraged. I had to find a way to be productive. I needed to have a purpose, help in some way,” she says. “For anybody just starting to go through it, the unknown is scary. Reading the illness’ effects from somebody that doesn’t have a political agenda gives it validity,” she says. “No one would, or could, give me any answers. If one person reads my story and now wears a mask — which has happened — or if someone laying in a bed alone, scared, and confused derives the strength to hold on a little while longer, it will have been worth it.”

Ariana Geneva

Ariana Geneva is a 33-year-old manager at a Memphis-area restaurant. She started feeling sick in mid-June.“It was in the 90s that week, and the Saharan dust cloud was moving through the atmosphere,” she recalls. “I chalked up not being able to breathe to be my asthma, and headaches to TMJ. I grind my teeth when I’m stressed. I still worked out, ran shorter distances — under two miles at a time — but it was super difficult. I had no energy.”

At the end of June, one of her co-workers tested positive for the novel coronavirus, and the entire staff went to get tested en masse on July 1st. “We all went to the Tiger Lane testing center, sat in line, and all got turned away because we didn’t have appointments, even though the websites say that between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m. you don’t need one. The testing site operator told us all to come back the next day at 8:30 a.m. and get tested, so we did. Came back that next morning to all get turned away again.”

The crew of 15-20 people finally got tested at Methodist Hospital. Two days later, Geneva’s test came back positive. Then she spent the month of July “rotating between my couch, my desk chair, and my kiddie pool in my front yard.”

Her fever spiked to 100 F, “high enough my bones and skin hurt,” and her shortness of breath intensified. After about 72 hours, her fever broke, and soon after, she could breathe easier. “I haven’t been able to taste anything since then however.”

Geneva says her test results came back promptly, but it took weeks for some of her co-workers to find out their status. A promised follow-up call from the Health Department never came. She says she had a persistent headache, and reduced stamina. “I’ve been able to work out after the fever went away. I work out every other day, but I have not been running,” she says.

Geneva believes that restaurant workers are particularly at risk from the virus, which spreads freely in close quarters.“People who work in restaurants always get sick. The public comes in sick, gets us sick, and we are all so close to each other in operation, once one person gets sick, it spreads. … Restaurants can’t operate with people standing six feet apart. It’s just not physically possible. It’s not an office or a classroom, where you’re stationary for most of your workings. There is constant movement in a restaurant.”

Now recovered and back at work, Geneva says people who refuse to wear masks “drive me batty,” and she hopes the habit will stick around after the pandemic subsides. “I don’t hate the mask thing. Do you know how many times I’ve bartended and listened to someone hack up a lung? All while I’m like ‘Cool, I’m trapped in this five-foot space with a plague rat.’”

Nancy Wilder

Nancy Wilder is a yoga teacher and 30-year resident of Memphis who is currently living in Franklin, Tennessee. In mid-June, her daughter and her boyfriend, who still live in Memphis, thought they were coming down with COVID.

“I told them to immediately get tested, so that they could at least start getting treated as soon as possible,” Wilder says. “The very next day, I met her halfway between Memphis and Nashville. I picked up my grandson from her there. I was certain that I could take better care of him, since I felt her tests were going to be positive. I thought from my experience, being a mom of three kids and a grandmother, that I could still take good care of him, even if I caught something.”

A day later, her one-year-old grandson developed a high fever that lasted for three days. Soon afterwards, Wilder started to feel like she had bad allergies. “Then, my daughter called to say, yes, her tests were positive. So then I said, ‘Okay, these weird things that are happening to me have got to be COVID,’ because by then I had developed a dry cough.”

The next day, she went to a clinic to get checked out. “When they saw me, they were used to the symptoms enough that they went ahead and got an ambulance for me and sent me to the ER, maybe because of my age of 65, maybe because I have an autoimmune disease. They were concerned for my heart, ’cause they were seeing a lot of heart problems.”

Wilder’s COVID test came back positive. “Then I knew I was in for a ride and I didn’t know what it was going to end up looking like.”

Her daughter recovered quickly, and came to retrieve her son as Wilder’s symptoms worsened. “I would never believe that would happen,” she says. “I’ve never not been able to take care of a child or someone in my household who is sick. And that was the case.”

Wilder’s doctor told her to “throw every over-the-counter medication that I could at the COVID. Medicine for cold, flu, or cough — anything I could to keep ahead of the symptoms to keep them from getting worse to where my lungs got so bad, I would have to go to the hospital.”

After 12 days of high fever, shortness of breath, and a light-headed feeling, “like I was floating above my body,” she started to improve. But it took a long time for her sense of smell and taste to come back. “About seven or eight days in, I tried to cook. I made spaghetti, and it tasted like warm pudding with texture. It was really gross.”

Wilder is now back to doing yoga two or three days a week, but her strength has not fully returned. While watching New York governor Andrew Cuomo reporting on the situation in his state on television, “I really developed a deep concern for Memphis because here I am in Williamson County, and there’s a sense here of being spread out. When I think of Memphis, with so many friends there, and my daughter and grandchildren, I think of the density. You’re much more in contact with other people. And, I thought, this is not good. This could be so serious for Memphis.”

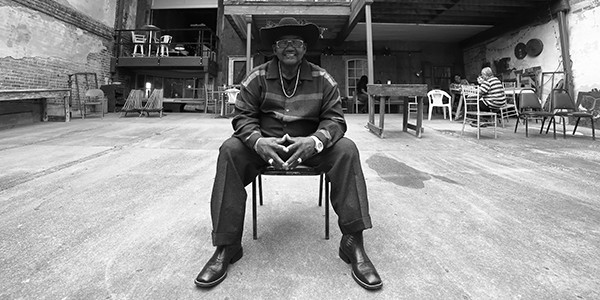

Rev. John Wilkins

To Mid-South music fans, Rev. John Wilkins, the pastor of Hunter’s Chapel Church in Como, Mississippi, is a treasure. Like his father before him, the 76-year-old makes music at the intersection of blues and gospel that has brought him international acclaim.

Wilkins says he was feeling fine until he fell out of the back of his truck on April 1st. Three days later, he still wasn’t back on his feet, and “my back was bothering me.”

His daughter Joyce took him to the hospital at Baptist DeSoto, but the family were not allowed to come in with him. “I called and told them they were going to keep me. And that’s all I remember,” says Wilkins.

“He didn’t have any symptoms,” says Miriam Triplett, a friend. “He was admitted in the hospital for his back, and we were informed that he had pneumonia and his oxygen level was low. After his daughter received notice about that, then they informed us later on that night that he was in critical condition and he was put on a ventilator. They had to open up the airways to his lungs for oxygen, because if he didn’t, they didn’t, he was going to die that night.”

Wilkins was unconscious in the intensive care unit for 17 days while his family waited and worried. “We were scared to death, but we were just blessed that he actually made it through,” Triplett says. “The Lord really favored him, to bring him out of what he went through, because he was in critical condition. At one time, they informed us that, that he would not make it, because of him being in such bad shape. But we trusted in the Lord and prayed that he made it through, and he came to.”

“After I woke up, man, I had to come to myself and realize where I was,” Wilkins says. “And then they found a blood clot in my leg and did surgery on me.”

Wilkins was in the hospital from April 4th to May 27th. “For you not to even have no relatives to be able to come see you or anything, that’s really scary,” says Triplett. “To be alone like that, and really not knowing what’s going on with you.”

Wilkins’ only contact with the outside world came when a nurse helped him use FaceTime to talk with his family. “He couldn’t do any talking, but she could talk and let him know that he wasn’t alone,” Triplett says.

“That was a real blessing,” says Wilkins.

Wilkins is back home, but is suffering from kidney damage from the coronavirus. He is now receiving regular dialysis treatment. “I tell you something else I wish I could get rid of: Ever since I come out of the hospital, I don’t have no taste. Nothing. I cannot eat.”

Wilkins advises people not to take this pandemic lightly. “Make sure you stay with a mask. Make sure you stay in the house. Because they don’t know what you got until they get you to the hospital. I’ve had about three or four preacher friends who went to the hospital and died. They said I was the only one at Baptist who went like that and came out alive.”

Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Adam Smith

Adam Smith  Mike Maple

Mike Maple

Alex Greene

Alex Greene  Alex Greene

Alex Greene  Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Augusta Palmer

Augusta Palmer