Leonardo DiCaprio wants you to know that he ate an elk heart, raw. DiCaprio is a vegetarian, but he ate that raw elk heart because Alejandro Iñárritu asked him to. DiCaprio was ACTING.

Last weekend, the Hollywood Foreign Press awarded DiCaprio their Best Actor award, and The Revenant Best Picture. Given that Iñárritu’s last film, Birdman, won Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay, the Golden Globe wins makes The Revenant the front-runner for the Best Picture Oscar. But is it the best film of 2015?

The short answer is no, but that’s mostly because 2015 was a banner year that included the stone-cold masterpiece Mad Max: Fury Road. But the longer, more interesting answer is that The Revenant is a monumental work from a filmic genius given free reign at the height of his power. And given that the film’s budget ended up ballooning from $60 million to $135 million, “free reign” seems like an accurate description.

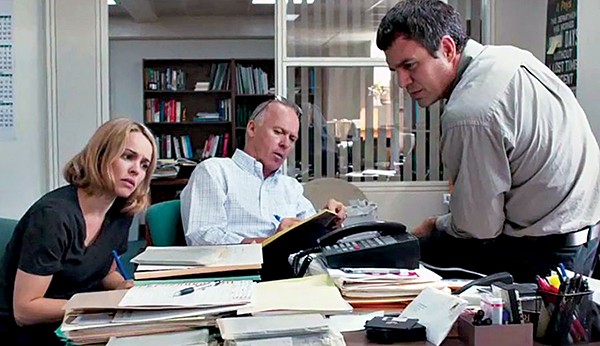

Hardy slays as Iñárritu’s villain.

Iñárritu’s got his Oscar, but DiCaprio does not, despite working with Steven Spielberg in Catch Me If You Can; Martin Scorsese for six films, including Gangs of New York and The Aviator; and, of course, James “King of the World!” Cameron for Best Picture winner Titanic. DiCaprio thinks it’s time he took home some hardware of his own, which brings us back to the elk heart. DiCaprio wants you to know that he will do literally anything to get that statue. So DiCaprio teamed with Iñárritu at exactly the right time.

Or possibly, from the point of view of DiCaprio’s health and well-being, exactly the wrong time. The Revenant is based on the story of Hugh Glass, a trapper and frontiersman who, during an 1823 expedition to what is now Montana, was mauled by a bear and left for dead by his comrades. But when he awoke to find himself not dead, he dragged himself more than 200 miles across the hostile, frozen wilderness to the nearest American settlement. In the course of Iñárritu’s epic retelling of Glass’ story, DiCaprio repeatedly dunks himself in freezing water, eats unspeakable offal, and spends at least 30 minutes of the almost three-hour movie foaming at the mouth while tied to a makeshift stretcher and being thrown through the forest by a gang of grumpy mountain men. It’s a ballsy, committed performance, and DiCaprio knows it. Occasionally, in one of his many close-ups, he stares into the camera with a look that screams “Are you not entertained?”

The film The Revenant reminds me of the most is Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, the 1980 Western epic that was such a disaster that its director is blamed for ending the American auteur period of the 1970s, when the director’s vision was paramount. There are some people who, to this day, defend Heaven’s Gate as a misunderstood masterpiece. Those people are mostly French, and they’re wrong. But imagine a world in which Cimino was right, and Heaven’s Gate actually worked. Accompanied, as in Birdman, by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, Iñárritu captures mind-destroyingly beautiful images of the West. The young crescent moon and Venus make frequent appearances in the sky, as do the shimmering red Northern Lights. At one point, they mix a giant avalanche with a normal reaction shot, and DiCaprio doesn’t even flinch. That’s how committed DiCaprio is: avalanche committed.

Somewhere along the way of this oversized adventure, the nonstop spectacle of inhuman endurance and existential questioning becomes overwhelming. To paraphrase Douglas Adams, The Revenant is like being beaten in the head with a gold brick. It’s actually an hour shorter than Heaven’s Gate, but still about 30 minutes too long. I do not envy the editor who had to decide what to cut from the constant cavalcade of beautiful shots, but that’s why they call editing “killing your babies,” and there needed to be more of that. I admit to having a love-hate relationship with Iñárritu, but I respect his skill and passion while still believing Birdman was a better distillation of his wild aesthetic than The Revenant. But yes, let’s give Leo his Oscar, please, so he can go back to eating healthy food, and maybe get warm.