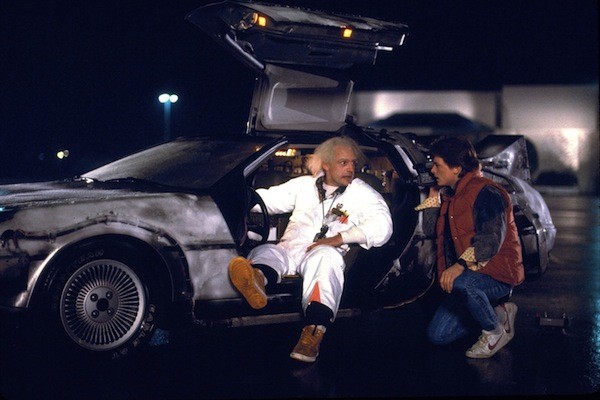

Battles Without Honor and Humanity (a.k.a The Yakuza Papers, Vol. 1) (1973; dir. Kinji Fukasaku)—The first film in Fukasaku’s pentalogy about organized crime in post-World War II Japan justifies its title almost instantly: the opening fifteen minutes include an atomic bomb detonation, a rape, two dismemberments, an act of yubitsume (“finger shortening”), an assassination, and a prison-cell seppuku with a homemade shiv. The violence never lets up, and as the paybacks and punishments proliferate, it becomes nearly impossible to keep track of who’s killing whom and why—which is probably the point. This much is clear, though: the city streets of 1940s Hiroshima were the meanest streets imaginable, and the desperate venality and violence of the strivers and thugs populating these films makes the tragic nobility given Michael Corleone and company in Francis Ford Coppola’s first two Godfathers look like delusional, naïve playacting.

Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a firestorm of scuffles, showdowns and ambushes that exposes the moral horror to criminal enterprise while mocking the solemn formality of the yakuza clan meetings alluded to via black-and-white photo montages and stentorian voiceovers. No one is safe: Fukasaku often freeze-frames his bad guys and labels them as important figures only to duck behind a car or another hoodlum as they get gunned down moments later, flailing and stumbling to their deaths and coated in liberal daubs of thick, fire-engine red movie blood. Each death is accompanied by a brassy horn blast on the soundtrack that’s part alarm and part wail of despair at the meaninglessness of it all. Closest thing to a credo in the film: “We’ll go back to our original vision of doing whatever we want to do.” Grade: A-

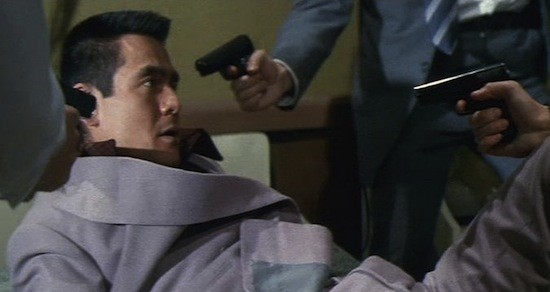

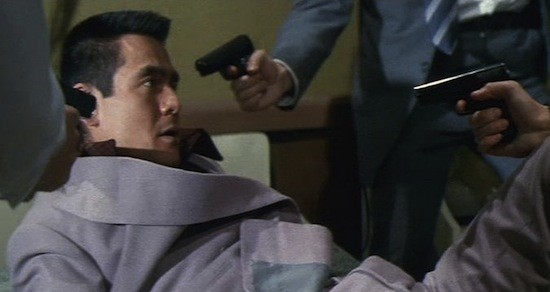

Deadly Fight in Hiroshima (a.k.a. The Yakuza Papers, Vol. 2) (1973; dr. Kinji Fukasaku)—With its streamlined cast and its third-act focus on a single character’s rise and fall, the second entry in The Yakuza Papers is the clearest and most accessible installment of the series. But it’s still an uncomfortable and clinical wallowing about in the underworld mud that’s punctuated by a handful of long, drawn-out and patently unfair confrontations between unsuspecting targets and sweating, frightened criminals who take a little too long to finish the dirty jobs they were sent to do. There are no master killers here—previous bloodshed hasn’t made any of the characters any better at murdering each other than they used to be. The bigger fight scenes resemble clumsy temper tantrums thrown by pretend gangsters who shoot their guns like they’re handling lit roman candles. They stab the barrels of their guns at their targets like preteen boys poking snakes and roadkill. And it’s not often clear who they’re aiming at. Instead of the battle royales crisscrossing the first film, this one relies on intergenerational rivalries, more occasions for dishonor and finger-shortening, and more explicit and overt political commentary in the voiceover narration. Sad personal goal: “Let me fight and die.” Grade: A

Proxy War (a.k.a. The Yakuza Papers, Vol. 3) (1973; dir. Kinji Fukasaku) Because nearly every gangster in the series harbors a pathological obsession with betraying everyone else, and because its many confabs are likely setting up the brawls of the final two films, the third Yakuza Papers is both the least action-packed and the most difficult to follow. It’s populated with official and unofficial meetings and counter-meetings overseen by whimpering businessman-goon types who weep crocodile tears as part of their own schemes for individual advancement. But Proxy Wars is still notable because it’s the one that finally lets scrappy lead dog Hirono Shozo (Bunda Sugawara) off the leash. Lingering in the background throughout the first two, Shozo emerges as a major player here, suffering through meetings like a born hoodlum in his blue pinstripe suit and beating his dumb employees like an unhinged dad. Formal note: if, somehow, you didn’t pay attention to Toshiaki Tsushima’s brooding musical score before, you will now. Its earworm repetitions are perfect for the third consecutive film in the series to end with a funeral and a desecration. Admission of defeat: “Wiping out your rivals doesn’t mean you win the game these days.” Grade: B

La Sapienza (2014; dir. Eugene Green)—And now for something completely different: important thoughts about architecture as spirituality made flesh, urbanization as man’s original fall from grace, wisdom as cosmic illumination and “ridding ourselves of the useless.” Writer-director Green’s stilted, pretentious, intellectually stimulating and frequently quite beautiful-looking story of an estranged middle-aged couple who meets up with a handsome, intensely curious teenage boy and his frail, wraithlike sister shows some necessary self-awareness about its own silliness early on, and it starts to trickle out more audibly once it becomes obvious that the camera and the actors are engaged in a staring contest that neither one is going to back down from. But who needs realism when Ozu is invoked as much as God and Borromini’s architecture (as well as Dardenne brothers regular Fabrizio Rongione) is there to generate some agape? The stiffness and artificiality of the performances don’t hurt the film at all—they actually reinforce the seriousness and importance of the age-old questions about art, buildings, knowledge (the “sapience” of the title) and love they boldly ask each other. It’s artsy as hell but pretty much irresistible. Epigraph: “Science without conscience destroys one’s soul.” Grade: A

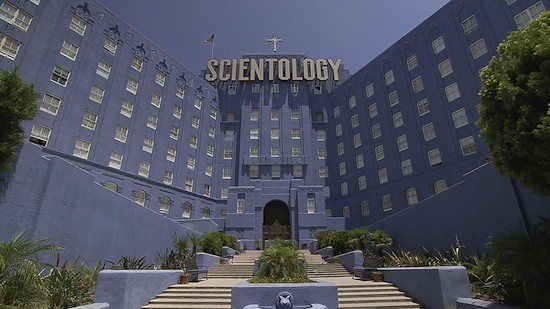

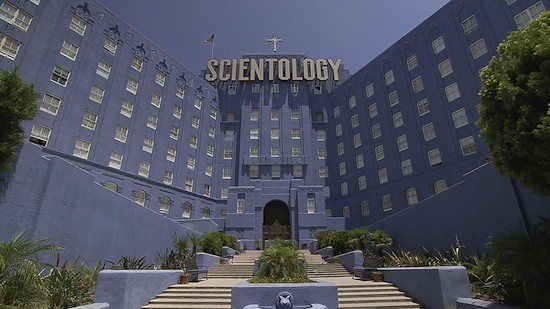

Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief (2015; dir. Alex Gibney)—The secret workings of the Church of Scientology are no longer secret. Both Janet Reitman’s Inside Scientology: The Story of America’s Most Secret Religion and the work of author Lawrence Wright (whose book Going Clear is the chief inspiration for Gibney’s documentary) discuss the finer points of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard’s origins and inspirations, the popular success of Dianetics, the billion-year Sea Org contracts, the panic over “suppressed persons”, the Bridge to Total Freedom, and the numerous accounts of member intimidation, exploitation and abuse. There are no Scientology surprises anymore; the big surprise will come—if it ever does—on the day the Church defends itself by citing something other than its own in-house websites and publications as proof that they’re innocent of all wrongdoing.

Going Clear mesmerizes anyway because it frames and explains Scientology as both a massively successful faith-based initiative and an All-American success story. Gibney charts Hubbard’s ideas as they evolve from a grab-bag of sci-fi concepts into the backbone of an extraordinarily well-funded and aggressive worldwide organization that used its money and muscle to force the IRS to suspend its investigation, declare Scientology a religion, and never try to collect taxes from it again. The thoughtful interviews with former Scientologists like writer-director Paul Haggis and former bigwig Marty Rathbun provide context and history. But Gibney’s doc also contains tantalizing archival footage of LRH himself—a seductive raconteur whose bad teeth would draw the ire of Mary Baker Eddy but whose undeniable self-confidence and personal charisma clearly continues to inspire super-secretive Scientology leader David Miscavige. HBO Films lawyered up big-time before releasing this one, but that’s more about Scientology’s rage for litigiousness than anything else: Gibney’s work is remarkably fair-minded given the xenophobia and strangeness exhibited by practicing Scientologists in clip after clip after clip. (Tom Cruise in particular does not come off well; wonder if any part of him thought Edge of Tomorrow was a documentary?) So why does Scientology continue to exist and expand? As Wright says, it’s not because its members don’t want to do the right thing: “They’re oftentimes good-hearted people, idealistic, but full of a kind of crushing certainty that eliminates doubt.” Grade: A-