Half the fun of being a judge at Memphis Italian Festival is hearing the stories about how the spaghetti gravy (“sauce” to some people) came about. A lot of times it was made from a recipe handed down from somebody’s grandmother and either tweaked or not tweaked.

But spaghetti gravy recipes also can be concocted by team members.

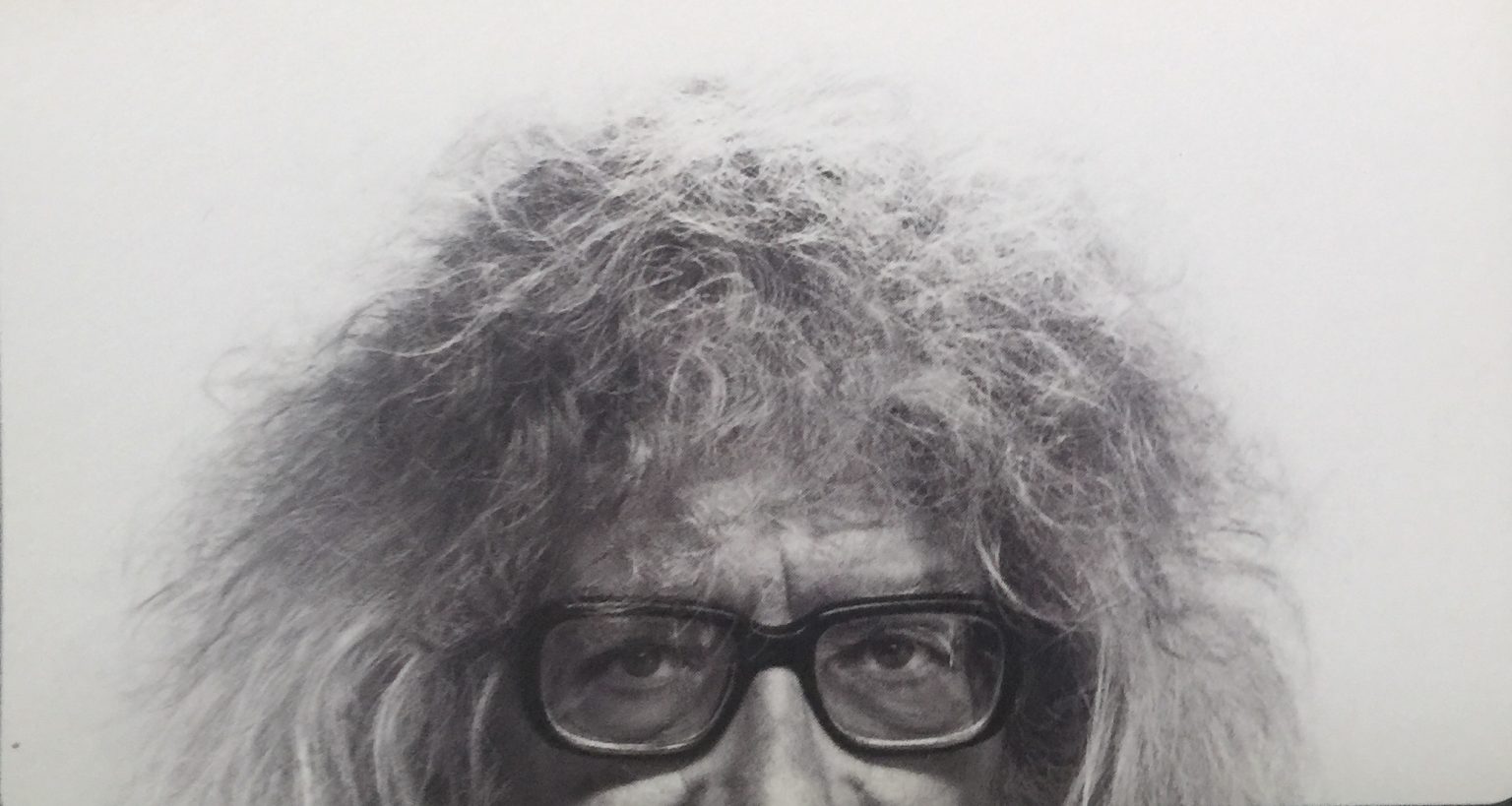

Like Jason McBride, 41, a member of Oliveus, one of the oldest Memphis Italian Festival teams. McBride created the spaghetti gravy, which was chosen by team members to represent Oliveus in the spaghetti gravy category at this year’s festival, which was held June 1st through 3rd at Marquette Park.

His recipe wasn’t handed down from his grandmother or anybody else, says McBride, who joined the team around 2016.

But he loves recipes. “A recipe is a storybook,” McBride says “And that’s something I’ve always enjoyed with cooking.

“There’s always a story behind it. Always a reason. And that’s just what I enjoy. That’s the fun of food for me.”

The story might be “Who created that recipe?” or “Who did you have that meal with?”

“For me, I can remember, as a child, cooking with my parents and my grandparents. And that carried on.”

The spaghetti gravy McBride came up with for this year’s festival includes pork sausage. “Everyone looks at Memphis and associates it with pork and barbecue. It was just a neat addition to continue on with this Italian dish. To me, pork is so versatile.”

McBride didn’t go to a grocery store or meat market to buy sausage. “The team has always made their own pork sausage.” And, he says, “We hand grind all the pork and season it. And we hand-make all of the sauces.”

What makes his sauce different is “the pork, the garlic kick, and then there’s a little bit of what I would call heat. Because there is a dash of red peppers. It’s got kind of a spicier kick to it than some traditional sauces.”

McBride also added some red wine.

Oliveus came in 11th place out of 39 participants in the spaghetti gravy category.

“They’ve been in the top as many years as I can remember,” says Richard Ransom, who, along with his wife, Vickie, are Memphis Italian Festival cooking team chairpersons.

For next year’s Memphis Italian Festival, McBride plans to come up with a new spaghetti gravy recipe, which he hopes his fellow team members will once again choose to represent the team. “For me, for the most part, the ‘game work’ I’ll call it, will always exist. I’ll always experiment with new ingredients and new seasonings and just see where it goes from there. For me, cooking is never this static product that never changes. The evolution of it is what’s fun.”

It was also fun for McBride to see his 11-year-old son Cooper taking part in Memphis Italian Festival. “He worked nonstop. This year in particular, he was in the kitchen cooking as soon as the festival opened and when it closed at night.

“He assisted with the gravies, pizzas, all the pasta dishes, meatballs, really the whole menu. He was a key player.”

It won’t be surprising to see Cooper one day representing Oliveus with his spaghetti gravy at Memphis Italian Festival.

“Instead of a basketball or a new bike, I just recently got him a new flattop grill,” McBride says. And it was a hit. “It was like Christmas morning for this kid. He was so excited.”

This year’s winners in the Memphis Italian Festival spaghetti gravy contest were:

1st Place – Pastafarians

2nd Place – Pasta La Vista

3rd Place – Foodfellas

4th Place – Molti Cuigini

5th Place – Da Friends

6th Place – Pazzo!