Forty years ago, a young devotee of power pop in general, and Big Star in particular, moved from North Carolina to Memphis. He worked in a sign shop by day, and cut demos at Sam Phillips Recording by night with drummer and producer Richard Rosebrough, who had, among other things, played on Big Star tracks. Though Chris Bell didn’t return his calls, at times the young Memphis transplant would encounter Alex Chilton. But, finding Memphis too hot, he soon left for New York, where he’d join up with some fellow North Carolinians who’d already released a single: the dB’s.

Norton Records

Norton Records

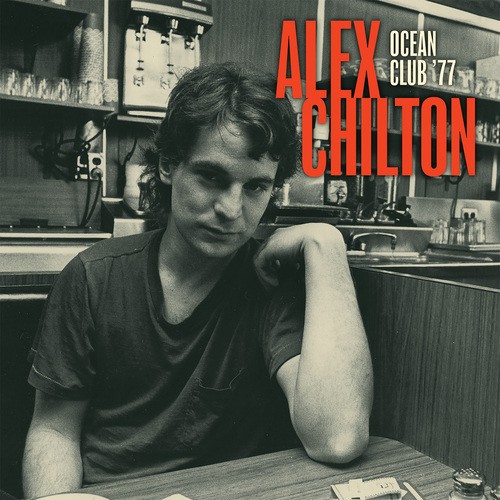

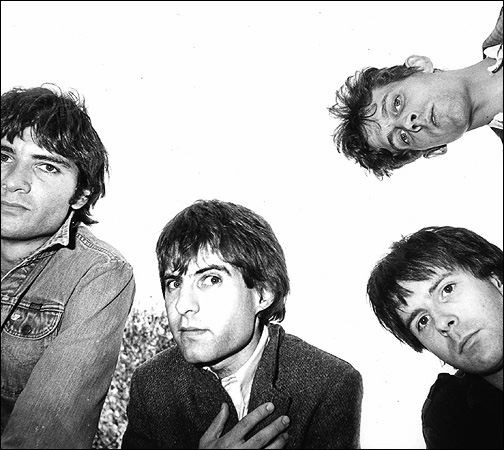

Naturally, this would be Peter Holsapple. The dB’s were much loved in their prime, though not considered a popular success. They were a perfect distillation of both 70s power pop like Big Star and more thorny New Wave sensibilities. Typically, however, the dB’s/Big Star connection that’s talked about most is by way of Chris Stamey. Stamey, who moved to New York before Holsapple, played with Chilton’s group the Cossacks, around the time that Chilton was living in New York and promoting his EP on Ork Records and regularly playing CBGBs and the Ocean Club. Stamey’s own label, Car Records, was the first to release Chris Bell’s “I Am the Cosmos” as a single. When Holsapple and friend Mitch Easter wanted to record their own single, Stamey arranged for Chilton to produce it.

The dB’s, ca. 1980

It was after all this that Holsapple moved to Memphis. Chilton had also moved back to his hometown, and the two connected sporadically here. Holsapple witnessed one of the Like Flies on Sherbert recording sessions, and connected with Rosebrough. It was a wild, unhinged time in the Memphis underground scene, soon to spawn the Panther Burns, but Holsapple was still reveling in the sounds of power pop. It wasn’t a perfect fit.

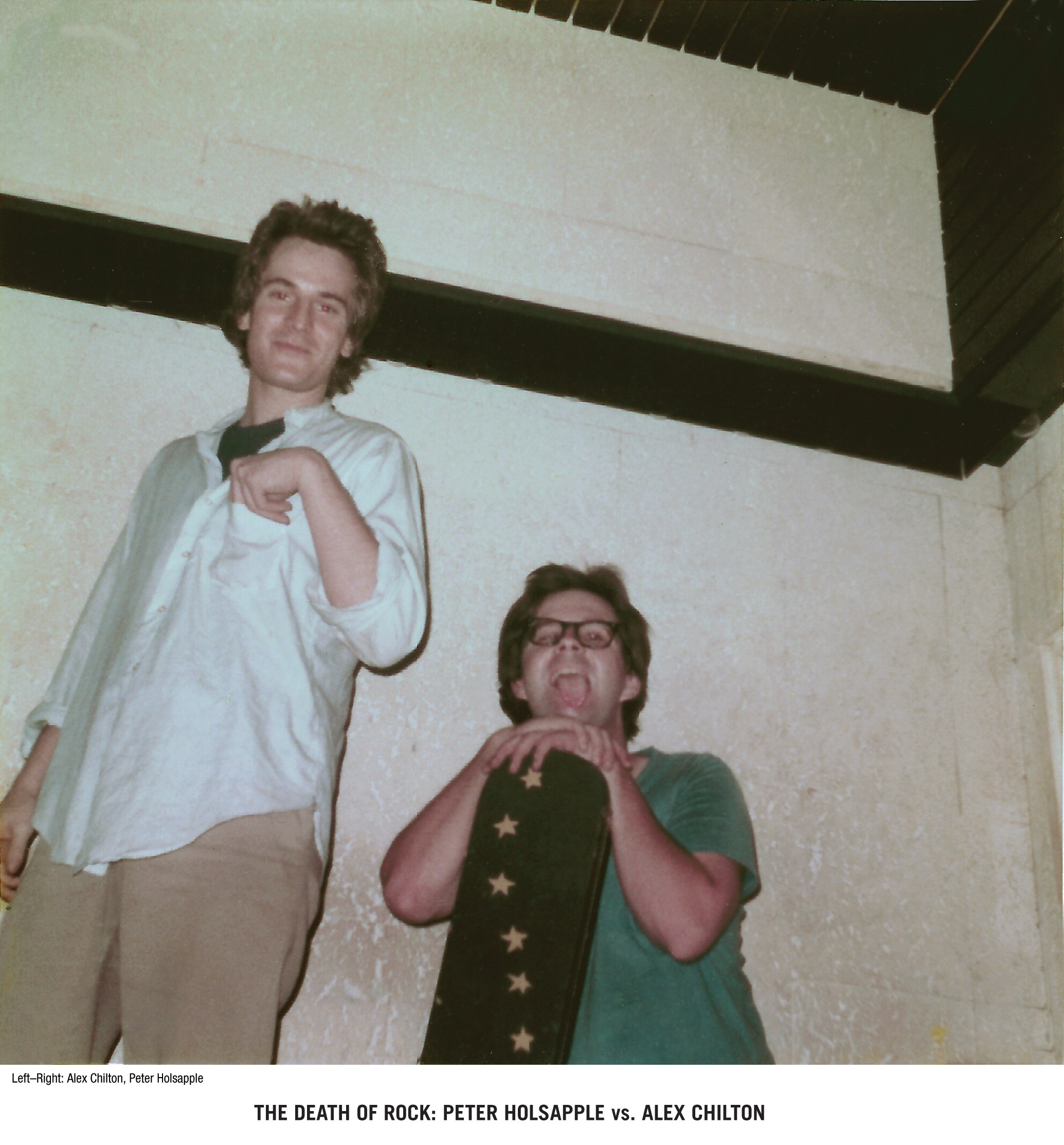

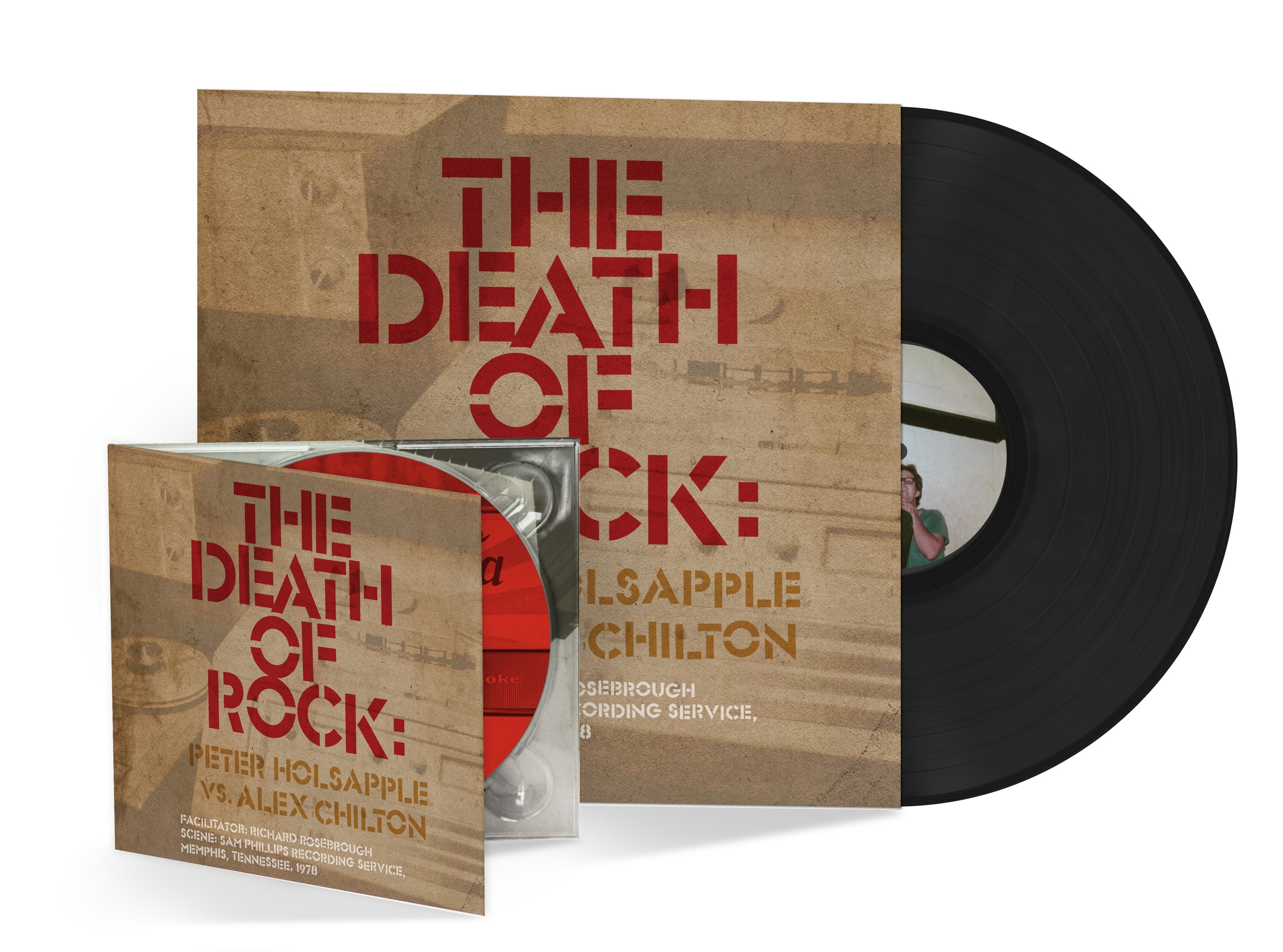

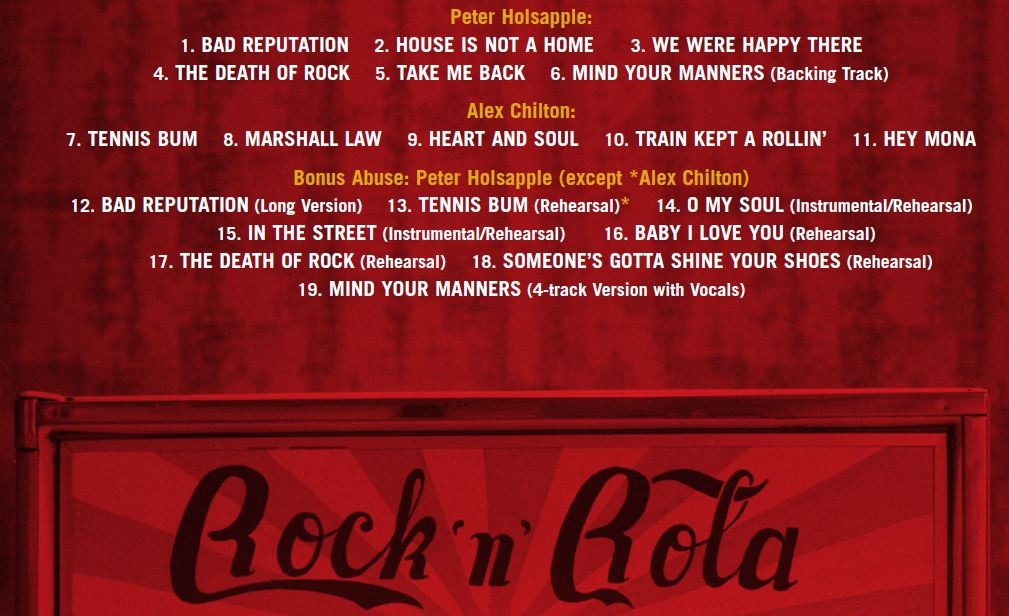

Such backstory is necessary to understand the context of an upcoming release on Omnivore Recordings, The Death of Rock: Peter Holsapple vs. Alex Chilton. The sessions Holsapple did with Rosebrough at Phillips did ultimately yield some tracks with Chilton, and now Holsapple’s demos and a few off the cuff numbers with Chilton form the basis of this release. And, as Robert Gordon writes in the liner notes, “It works out OK for both artists, the collaboration taking each somewhere they’d likely not have gone by themselves.”

Yet the “versus” tag is appropriate, for the clash of sensibilities is palpable. As Holsapple writes in the liner notes, after buying Chilton a beer one night, the ex-Box Top quipped, “I heard some of that stuff you’re working on with Richard . . . and it really sucks.” It was in perfect opposition to the direction Chilton was headed. Holsapple goes on, “I caught Alex exiting a world of sweet pop that I was only just trying to enter, and the door hit me on the way in, I guess.”

If you’re unaware of the 70s and 80s work of either artist, stop reading and get yourself to a record monger. Most of these cuts are fascinating as embryonic versions of other recordings, especially the Holsapple material. Two songs went on to become fully realized dB’s tracks, and should be heard in those incarnations. Other Holsapple songs are not necessarily his finest work, though they are interesting excursions down Power Pop Boulevard. Still, one must brace oneself for the reaching vocals, tentative guitars, and lowered expectations of a rock demo — not everyone’s cup of tea. My first reaction, upon hearing Holsapple’s classic tunes here, was, “Wow, the dB’s were really good.”

But my second reaction was, “Wow, Richard Rosebrough was really, really good.” Indeed, he’s the unsung hero of these sessions, combining the sheer power of his drumming with a sensitivity to song structure. Ken Woodley is his perfect partner on bass. Hearing Holsapple’s material with Rosebrough’s heavier, slower beats is a telling contrast with the sound of dB’s drummer Will Rigby. It’s perfectly suited to one Holsapple original that never made it to dB’s, “The Death of Rock.” It’s ironic, given Chilton’s devotion to deconstructing rock norms at the time, that Holsapple wrote the number. Yet the song itself is more in keeping with Holsapple’s bigger, grander vision of power pop than the rootsy mess Chilton was embracing. Though it should be noted that Holsapple’s “Someone’s Gotta Shine Your Shoes” is a perfect fit with the Sherbert sound and allows Rosebrough’s heaviness to shine in an uptempo context.

And of course, it’s great to hear Rosebrough and Chilton together. There are a couple of Big Star tracks that the two lay into with punk abandon. That partnership was flourishing at the time, during the sessions for Like Flies on Sherbert. When it came to the chaotic stomp of that era of Chilton recordings, Rosebrough got it, and it shows on the half dozen Chilton tracks here. And, though chaos was certainly Chilton’s calling card at the time, it’s revealing that his tracks here sound clean and tight in a way that Sherbert did not. Unlike Holsapple, who was reaching for new heights, Chilton had been to the heights and was now abandoning them to do exactly what he wanted, using simpler forms in unpredictable ways. The clarity of his focus brings a cohesion to his tracks that Holsapple’s lack.

“Tennis Bum” is already known to those true lovers of Chiltonia who snagged the Dusted in Memphis bootleg in the 80s, but there’s a greater clarity to the sound on this official release, as Chilton paints a portrait of Midtown slackerdom. “Marshall Law” [sic] is a perfect gem of paranoia, an ominous chugging drone contrasting with Chilton’s feckless delivery of images like “automatic weapons slung over their shoulder…tanks taking positions…chaos prevailing all over!” As Holsapple writes, the song “referenced the Memphis Police and Fire strike that was going on, curfews and sharpshooters on top of downtown buildings at night.”

Equally clean and chaotic, again, is Chilton’s take on the chestnut “Heart and Soul,” in which he mischievously changes key in the middle of the melody. His cover of the Johnny Burnette’s “Train Kept A-Rollin’” is fairly straightforward, compared to the Panther Burns’ versions yet to come. But his take on Bo Diddley’s “Mona” is a revelation, breaking down into some feedback-drenched guitar work that echoes the Cubist Blues he would later record with Alan Vega and Ben Vaughn.

In the end, then, this disc is well worth the price of admission. Revisit your dB’s records, and Chilton’s Like Flies on Sherbert, then dive into this time capsule to get another peek into the zeitgeist of late 70s Memphis, where anything seemed possible, “anything goes” was the imperative, and oil and water mixed for a time.

The Death of Rock: Peter Holsapple vs. Alex Chilton will be released October 12.