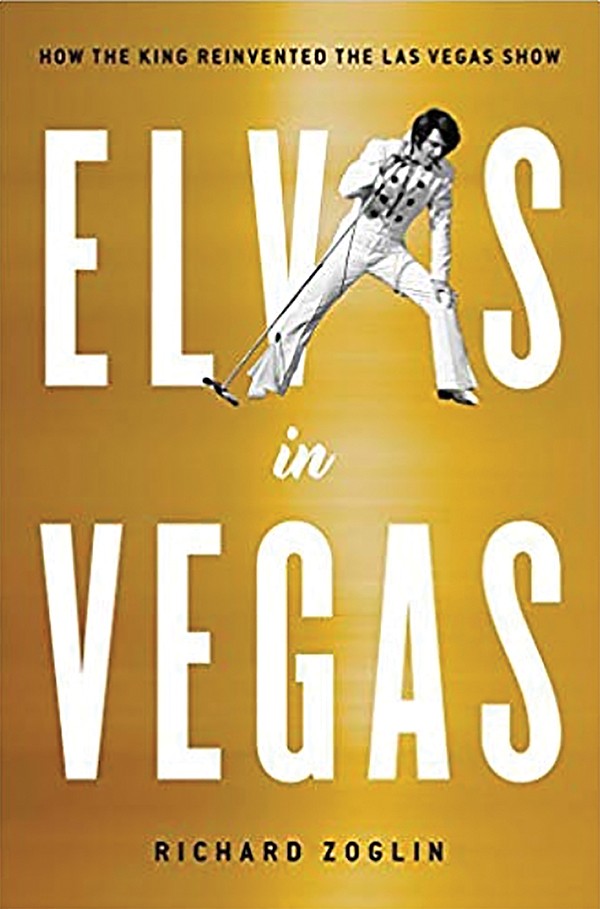

The conventional wisdom is that Las Vegas is to blame for the ultimate demise of the King of Rock-and-Roll. Though Elvis Presley was at his home in Memphis when he died, some fans and music historians trace his downfall back to his tenure as a star in Las Vegas, Nevada. Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Vegas Show (Simon & Schuster), the new history by Richard Zoglin, argues differently. “Las Vegas saved Elvis, at least for a little while,” Zoglin writes, “and Elvis showed Vegas its future.”

In Elvis in Vegas, Zoglin sets up what he calls “the greatest comeback in music history” with the precision of a patiently plotted thriller. Rather than offer a blow-by-blow account of the minutiae of Elvis’ career as a Vegas performer, the author gives an overview of Vegas’ history as an entertainment town, starting with the showgirls of Minsky’s Follies and the jazz-and-booze-flavored machismo of the Rat Pack. It’s a useful overview, for one must understand what Las Vegas represents in the American unconscious to understand the King’s rebirth there.

“It was naughty entertainment for sheltered middle America, helping to loosen the Puritanical standards of the Eisenhower-era ’50s and opening the door to the more audacious taboo-breaking of the late ’60s,” Zoglin writes of Vegas’ early years as more than just a destination for gambling.

Not to fear, diehard Elvis fans; long before the formation of the TCB Band and his stint as a Vegas entertainer, Elvis appears on the pages of Elvis in Vegas. He performed in Sin City early in his career, and he returned again and again to cruise the strip and take in the shows, even before his trendsetting tenure as a Vegas performer. Elvis was drawn back by the late nights and carnival atmosphere, a drastically different environment than the one he was used to in Memphis. In fact, it was a member of the Las Vegas tabloid press who coined the term “Memphis Mafia” as a nickname for Elvis and his coterie of friends and hangers-on, who enjoyed cruising the city in black mohair suits and dark sunglasses.

As Elvis ushered in the age of rock-and-roll, he helped bring about a sea change in Las Vegas, long before his tenure there. The Vegas of the Rat Pack was segregated, somewhat salacious, and dangerous. And, as they always do, the tides of culture changed. “By the late 1960s, Vegas was beginning to lose its juice,” Zoglin explains. “Beatlemania was hardly the passing phase that Vegas thought — hoped — it might be.”

Changes in culture and in appetites reflected behind-the-scenes shifts in Vegas’ business landscape as Howard Hughes bought up property and subverted, to a degree, the mob’s influence. And Elvis, in the process of reinventing his career after spending years filming 31 motion pictures and not touring, was poised to fill the entertainment vacuum.

The stage was set for Elvis, and, fresh from his reinvigorating ’68 Comeback Special, the King was ready to ascend to his throne, not just as the King of Rock-and-Roll, but of America’s collective fantasyland. Always a gifted arranger, Elvis set about cultivating his TCB Band with a renewed energy. “This was the deprived musician, who had not been able to control his music either in the recording studio or in the movies, and now he was going to satisfy all his musical desires on that stage,” Zoglin quotes Jerry Schilling, one of Elvis’ longtime friends.

Elvis incorporated elements of all his interests into his Vegas show. Gospel, rhythm & blues, symphonic pop, his friendship and admiration of Liberace — Elvis was more vivid than any time since before joining the Army. At last free of, as Zoglin calls it, manager Colonel Tom Parker’s “non-stop movie treadmill,” Elvis crafted a dynamic, sensual stage show backed by a full band and back-up singers. Where the Rat Pack had been cool and removed, a booze-fueled boys’ club, Elvis was passionate and direct, as tangible as a sweat-stained scarf thrown to the crowd.

In Vegas, with its Elvis impersonators, tribute shows, and Elvis-themed wedding chapels, Zoglin writes, “Elvis, of course, never really left the building.”