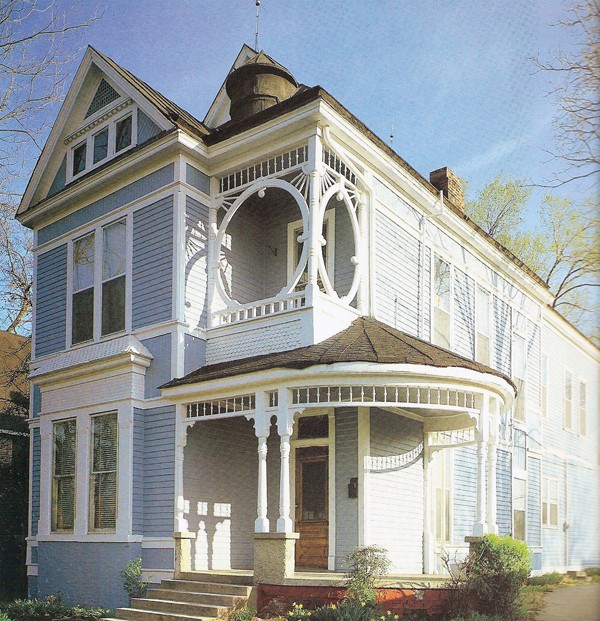

In 1883, cotton merchant Newton Copeland Richards built a stately Queen Anne-style home with a rounded porch and circular balcony latticework at 975 Peabody. Richards went on to become the president of the Memphis Cotton Exchange in 1902.

But today the crumbling Richards House, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is hardly fit for a president. Or anyone for that matter.

“It’s been in dire shape cosmetically for years. It looks like you could blow on it, and it would come down,” said June West, executive director of Memphis Heritage.

But thanks to a 2007 state law aimed at curbing blight in urban areas, Memphis Heritage has entered into a receivership of the home. It has partnered with locally based Rising Phoenix Development Group to restore the property back to its original glory.

The property owner at 975 Peabody was sued under the Neighborhood Preservation Act, which allows an interested party to sue a property owner if their property is vacant and uninhabitable. In a first for the preservation organization, Memphis Heritage was named as the receiver of the property.

Courtesy of Memphis Heritage

Courtesy of Memphis Heritage

(Left) Historic Richards House in its better days; (Right) June West and Joey Hagan of Memphis Heritage with Varanese Pryor and an intern from Rising Phoenix on the porch of the present-day blighted Richards House.

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips

Here’s how it works: If, after being sued under the Neighborhood Preservation Act, the owner is unable to pay for repairs or demolition, the Shelby County Environmental Court may appoint a receiver to develop and carry out a plan to rehab the property using the receiver’s own funds.

Once that property has been restored, the owner has the option of taking it back by paying the receiver the cost of repairs and labor, plus an additional 10 percent. If the owner cannot or does not wish to pay, the property would go up for sale in a public auction. If it doesn’t sell to a third party at auction, the receiver may take the title to the property as the sole bidder.

Since Memphis Heritage isn’t in the business of restoring homes, it has teamed up with Rising Phoenix Development Group, a blight remediation nonprofit that both works to physically repair properties and offers vocational training and financial planning to people living in blighted neighborhoods. West said they’ll assist Rising Phoenix with marketing the project and fundraising.

Varanese Pryor, CEO/owner of Rising Phoenix has big plans for restoring the Richards House.

“I’ve moved into the community, and I’m getting to know the people who will watch this change, develop, and grow,” Pryor said.

If the property owner, who hasn’t lived in the home for nearly a decade, doesn’t pay back the funds used to fix up the home, and it doesn’t sell at auction, Pryor plans to use the home as the headquarters for Rising Phoenix.

Although the outside of the house looks worse for the wear, West said the home’s “bones are still good.” The original gingerbread latticework over the stairs, the mantles, and the gas lighting system have been maintained.

“There is some water damage in the walls and a lot of plaster damage,” West said. “But the original structure of the house is in good shape.”

Joey Hagen, president of the Memphis Heritage board of directors, believes this receivership process might help the organization save other blighted historic properties.

“If this works, this opens a whole new avenue of possibilities for Memphis Heritage to be more proactive,” Hagen said. “We’ll be able to target properties before they become super-endangered.”