In my semi-regular Never Seen It column, I find an interesting person and sit down with them to watch a classic (or sometimes, not-so-classic) film they have missed. This pairing of subject and object may be the most perfect one ever. Jesse Davis recently took over the reins of the Memphis Flyer from his semi-retiring predecessor Bruce VanWyngarden. Davis had never seen the greatest film about journalism ever made, the 1976 political epic All The President’s Men. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Chris McCoy: Jesse Davis, what do you know about All the President’s Men?

Jesse Davis: Almost nothing. I know it’s based on a book of the same title by Woodward and Bernstein, and that it’s about their investigation into the break-in at the Watergate hotel. And that’s it.

138 minutes later…

CM: We’re on the record with Memphis Flyer editor, Jesse Davis. You are now a man who has seen All The President’s Men. What did you think?

JD: I really enjoyed it. It was absolutely excellent. It was a great story. I know Watergate and Nixon is one of those areas of U.S. history that attracts a lot of people, and for some of them, I’m sure, it’s because they have seen this movie. But it has struck me as something that was kind of like JFK’s assassination. There were a few events that are understandably interesting, but some of the people who are really, really, really into them do not … um … do not emit an aura of being really well put together.

CM: That’s diplomatic.

JD: I mean, like I said, I can understand the interest, but …

CM: They’re obsessions of the dirtbag left, is what you’re trying to say.

JD: That might be one way of putting it.

CM: Guilty as charged.

JD: You know, there are some things where most of the people who are interested in it, you’re like, “Oh God, are you guys okay?” I think some of my first contact with people who were really obsessed with Watergate was like that. But not everyone. I mean, it’s notably interesting. The whole truth and power and accountability dynamic is just as important today as it was in ’72. So, I mean, it’s understandable why folks would be interested. But I say all that to say that I never dove really deep. I’ve not read the book. It’s absolutely interesting to see them follow the trail.

CM: It’s a journalism procedural story, which you don’t see a lot of now. I mean, procedurals are like three hours on CBS every night, but it’s always law enforcement. It’s never journalists anymore. One of the things that’s interesting to me about this film is that journalists are the protagonist. You know, Superman was a journalist. Then there’s My Girl Friday, and lots of others. Wasn’t Mary Tyler Moore a journalist for a news station? But you don’t really see that much anymore. There was Spotlight a few years ago, which was great. Maybe part of it is that it’s just people sitting around in rooms talking.

JD: Or talking on the phone!

CM: But also, part of it is, there was a shift where people don’t trust journalists absolutely anymore. Watching it this time, I think it’s interesting that a lot of what they were doing seemed to be responding to a narrative that the Washington Post and other papers were creating together at the same time. It struck me that a lot of what the disinformation plague does is to destroy the possibility of a central narrative. So you don’t have to prove that you didn’t lie. You just have to make it so the truth is not actually knowable. That’s a big question that’s hanging over this movie: Is the truth knowable? Or are these people, in fact, like you said, “not very well put together”? Bernstein is clearly not very well put together.

JD: This is true. He’s smoking cigarettes constantly — in a restaurant, in other people’s homes, in other people’s cars, in the elevator …

CM: The elevator smoking is funny. It’s the only time anyone comments on it.

JD: Whoever the cinematographer is, [ed note: Gordon Willis] is doing things to make shots of people talking on the phone visually interesting. Maybe that’s one of the main differences, but I’m sure a lot of law enforcement is actually pretty boring.

CM: Those procedurals on CBS every night, they’re just mostly people talking in rooms, too. But every now and then, they run around and wave guns at each other.

CM: I pointed out a couple of split diopter shots, which is a thing you put on the front of a lens that has two tinier lenses with different focal lengths. There was the one shot where Woodward’s on the phone in the foreground, and I guess they’re watching some kind of sports match in the background. There’s two different planes of focus in the same shot. This is not done in post-production. It was done in-camera, live. Right when Woodward gets the information he’s looking for, the people in the background cheer. It’s real subtle. You just don’t see that anymore.

JD: It was set up under the sign for the national news desk, which I thought was nice. There’s whatever game was on the TV, and then there’s this national game going on, and Robert Redford just scored.

JD: Another thing I noticed is, when Redford’s going into the parking garage, and when they’re at work, you see all of this space around them. They’re lost in all this, whether it’s the architecture of the parking garage or the columns in the newsroom, and trying to find their way out. We know that they’re the figures we’re supposed to be paying attention to, but you see all of the Washington Post newsroom, or all of the parking garage, or a big part of the D.C. skyline. At one point, I think it was Robert Redford, maybe, walking with the Washington Monuments behind him. They’re these huge buildings, and he’s just this tiny little figure. I loved that repetition, and the difference in scales.

CM: There’s very much a sense of millions of people going on with their lives who have no idea that what this guy is doing is going to change history. It’s going to bring down the president.

JD: A line I love, early on, is when their editor says about the story, “It may just be crazy Cubans.” The idea of someone saying that about this story! As an editor, that’s a pratfall. You just don’t know. There may not be a story.

CM: That was going to be my next question. You’ve been editor of the Memphis Flyer for what …

JD: Six weeks now.

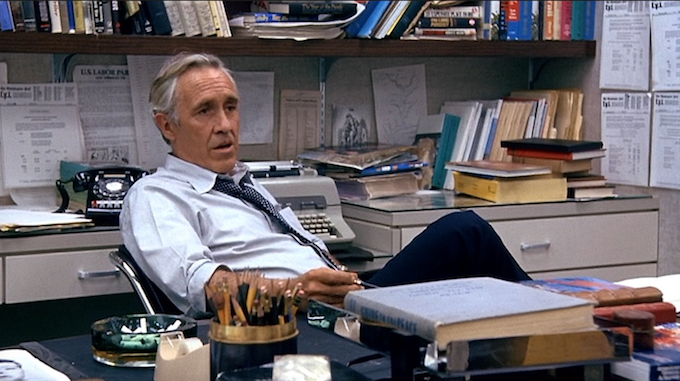

CM: Ben Bradlee, who was Jason Robards, is just an absolute legend in the industry. What were you thinking about when you were watching him?

JD: In the beginning, everything is set up to make you feel like he is maybe one of the forces who wants to kill the story, for whatever reason. Then there’s a scene where they talked about how it could put them in legal trouble. And for all you know, it could. There’s a little while before he has this moment where he tells them about a time he screwed up, but he got the story right. But it’s a while before we get to that point, and all of his concerns are completely justified. He’s just like, look, you’ve got to have multiple sources, especially if these people aren’t letting us name them. You have to corroborate this. But we can’t know if that is really his justification, and it’s all in service of good reporting. If so, that’s great, but there’s a little bit of tension there — especially the more you start to think, “OK, there are some layers of conspiracy going on. How do I know that they didn’t get to him?” When [White House spokesman Ken W. Clawson] calls him panicking and says, “I got a wife and a family and a dog and a cat,” he’s on a first name basis with [Bradlee]. And you’re like, he’s editor of a big paper. Maybe pressure has been put on him. But then, once he gets to the point where he’s satisfied, he puts out his statement: “We stand by the story.” I’m going to keep these guys on it.

CM: And that was a crisis point in the story. That’s after they’ve been burned by their sources on purpose, to throw them off.

JD: He sensed that was what was happening.

CM: What’d you think about the actual, nuts and bolts of reporting in 1972? How does it compare to what the experience is like today?

JD: Well, first of all, Memphis Flyer is not a daily, so it’s a completely different thing.

CM: You do one layout a week. Those guys were doing layouts every day. You know, the editorial meeting scene is so fascinating to me.

JD: I love that scene. They go around, and everybody says what they’re working on, and then it’s okay, go around again. This time it’s just the really short pitch. And this is how much space you get. That was, that was great, and very different.

CM: Currently, our editorial meetings take place on Slack. But we still sit around and talk about what we’re going to put in the paper. There’s still magic in that moment, to me. There’s a romance to it, I guess.

JD: I think so, too. I mean, it’s different. They’re the Washington Post, and we’re an alt-weekly, we’re the Memphis Flyer. It’s the ’70s. It’s 2021.

CM: Not a computer in sight.

JD: When they’re going through the list of names, I thought, “Oh my God! Imagine doing this without the internet!” It’s a completely different thing. But there’s still a huge amount of talking on the phone. Now, it’s just Slack, but before the pandemic, when I was the copy editor, I walked back and forth between different parts of the office all day, every day. So there are still elements that are the same. But yeah, the editorial and layout meetings, I think are incredibly magical. They have a big enough staff that it’s like, “What things have y’all been working on that are now ready for us? What’s ripe?” There’s an element of that, but I expect you’re going to have a film review every week.

CM: There was the moment where they’ve been knocking on doors, and they haven’t produced any copy for two weeks. You know how much copy I’m expected to produce in two weeks?

JD: Oh yeah.

CM: They have an enormous amount of resources we don’t have, that barely anybody has outside of The New York Times or the Post or the Wall Street Journal has now.

JD: To just be able to send somebody on assignment, and tell them to keep going until you turn something up or don’t … If someone’s working on a cover story, sometimes there’s a really quick turnaround, but often, that’s something you are taking back and forth between the back burner and the hot burner until it’s scheduled to go. But it’s not like we don’t do research.

CM: Oh, I didn’t mean to imply that we don’t do research, because we absolutely do. That’s most of my time, really. But to be able to fly down to Miami, barge into the D.A.’s office, and demand they talk to me, I can’t imagine doing that and being treated with anything but contempt. It’s a great moment in the movie, because he plays this trick on the receptionist, but there’s no way I could get into the D.A.’s office, and then the D.A. does anything except have me arrested.

JD: Sometimes, you see, in a work of fiction, someone who’s a magazine writer or a newspaper writer, and they appear to have a huge budget and really flexible deadlines. And you’re just like, “Well, that’s fiction. That’s based on an old idea, a different time period.” It kind of makes me think of hard-boiled films and private detectives. How would Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade go over today? The industries are different, and the laws that have continued to grow up around policing and investigative journalism are different.

JD: One thing I noticed in two of the TV clips was, you’ve got someone talking about their sources and he uses the word “unsubstantiated.” In another, they were talking about the political leanings of the editor of the Post. First of all, just to have someone holding national office say the word “unsubstantiated,” that felt very strange, um, particularly after the last four years or so.

CM: Trump would have said, “Fake News! Enemy of the state!”

JD: Exactly. It’s the same with, “I think we can make a safe assumption about his political leanings.” I’m paraphrasing there, but that’s very different from “They’re the crooked Democrats, and we all know they want to take us down!” But it’s all of a piece …

CM: It’s the evolution of that rhetoric, which began with Nixon.

JD: You could say it’s based on logic, and maybe it is. Now, we have mutated or evolved this line of defense so it is just the quickest and most direct route to an emotional reaction: I’m under attack by these people, and you should — to use the phrase they used in the movie — circle the wagons. I’m going to protect my president from these rats.

CM: You got the sense that the people who were in Nixon’s inner circle, the Republicans he was ordering to take these illegal actions had a lot more autonomy back then. The give and take in this part of the drama is, are they going to do their duty to the country and the Constitution, or are they going to put party first? You know what they’re going to do now.

JD: Oh, well, of course!

CM: They’re going to put party first. Donald Rumsfeld died today, the day we’re recording this. Back in the Rumsfeld era, the ’00s, after 9/11, I used to sometimes read this blogger — it was the blogger era, too — called The War Nerd. One of the things he liked to say was, the more organized side is the one who usually wins. He also used to say, “The end of the world is what you call it when your tribe loses.” I feel like what we’re seeing today is like the evolution of that thinking, which is, frankly, pure fascism. That’s the definition of fascism: I have loyalty to this narrow in-group, right or wrong, rather than loyalty to the Constitution, or to the greater good, or to the nation. My faction is what’s more important. And I felt like it was really obvious from this film how far we’ve sunk.

JD: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, that’s without question.

CM: And yet, in the Trump years, or so far, anyway, the same systems held that held against Nixon, pretty much. It just felt like a much closer thing this time.

JD: Yeah, I think so, too.

CM: Did it make you reflect on what your duty is as an editor of a paper?

JD: Well, first of all, I gotta get a good “shut the hell up” look.

CM: You gotta get that.

JD: That’s important. I’ve got to stay cool under pressure, and then know when it’s time to start dropping F-bombs, and just say, “Well, it’s only the fate of democracy and free speech. Don’t fuck it up, or I’ll get mad.” His responsibility to the truth, and to getting the reporting right, seemed to be the highest ideal. Obviously, how that affects our paper and our image is incredibly important. Everything flows from telling the story accurately. That seems to be his primary action in the film. So that first day you’re not reporting it well enough, I gotta tell you to dig deeper, and then recognize that we’re now in hot water. I will stand up. I’m with you guys. You’re showing up at my door. It’s late at night. You’re saying it’s not safe to come inside.

CM: I’m telling you we’re being bugged by the CIA. Do you believe me?

JD: Okay, let’s have this conversation on the lawn. I like to think that if any of our writers show up at my house and tell me that, I’m glad it’s the CIA! I’ll say, “God, we’ve got an amazing story here.”

CM: I’d say, “You’re aware you work for the Memphis Flyer, right?”

JD: In some ways, they lucked into things because of having people just take calls, which doesn’t happen now. Someone got into the rhythm of answering questions and said something they shouldn’t have. I don’t know that we’re necessarily going to get that as frequently as they did just by cold-calling people. Then there’s their little routine of casually dropping a piece of information that we want confirmed.

CM: We’ll pretend we already know it.

JD: Yeah, exactly. Or, we’ll argue about the details of something that we think we know, but we’re not sure we know. And then, if there’s no issue from your interview subject about the thing in question, it’s like, okay, now we really are talking about it.

CM: I actually had an opportunity several years ago to pull the “I’m going to give you some initials, and I want you to say yes or no” gag. I felt like such a badass! But the only reason I knew to do it was because of this movie. So would you recommend All the President’s Men to people?

JD: Oh, wholeheartedly. I think if you walk away from it feeling like, “This was a David and Goliath story, and I believe that can happen because it did happen and they were successful,” then that’s great. If you walk away from it thinking, “Those were some cool shots,” that’s great, too. If you walk away from it with “The truth matters and I want to help tell it,” well, that’s even better.