It’s fashionable to complain about how bad Hollywood movies have become. But from the perspective of a critic who has to watch it all go down, it’s simply not the case. At any given time in 2015, there was at least one good film in theaters in Memphis—it just may not have been the most heavily promoted one. So here’s my list of awards for a crowded, eventful year.

Worst Picture: Pixels

I watched a lot of crap this year, like the incoherent Terminator Genysis, the sociopathic San Andreas, the vomitous fanwank Furious 7, and the misbegotten Secret in Their Eyes. But those movies were just bad. Pixels not only sucked, it was mean-spirited, toxic, and ugly. Adam Sandler, it’s been a good run, but it’s time to retire.

Actually, I take that back. It hasn’t been a good run.

Most Divisive: Inherent Vice

Technically a 2014 release, Paul Thomas Anderson’s adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s ode to the lost world of California hippiedom didn’t play in Memphis until January. Its long takes and dense dialogue spun a powerful spell. But it wasn’t for everyone. Many people responded with either a “WTF?” or a visceral hatred. Such strongly split opinions are usually a sign of artistic success; you either loved it or hated it, but you won’t forget it.

Best Performances: Brie Larson and Jacob Tremblay, Room

Room is an inventive, harrowing, and beautiful work on every level, but the film’s most extraordinary element is the chemistry between Brie Larson and 9-year-old Jacob Tremblay, who play a mother and son held hostage by a sexual abuser. Larson’s been good in Short Term 12 and Trainwreck, but this is her real breakthrough performance. As for Tremblay, here’s hoping we’ve just gotten a taste of things to come.

Chewbacca

Best Performance By A Nonhuman: Chewbacca

Star Wars: The Force Awakens returned the Mother of All Franchises to cultural prominence after years in the prequel wilderness. Newcomers like Daisy Ridley and Adam Driver joined the returned cast of the Orig Trig Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher in turning in good performances. Lawrence Kasdan’s script gave Chewbacca a lot more to do, and Peter Mayhew rose to the occasion with a surprisingly expressive performance. Let the Wookiee win.

Best Memphis Movie: The Keepers

Joann Self Selvidge and Sara Kaye Larson’s film about the people who keep the Memphis Zoo running ran away with Indie Memphis this year, selling out multiple shows and winning Best Hometowner Feature. Four years in the making, it’s a rarity in 21st century film: a patient verité portrait whose only agenda is compassion and wonder.

Best Conversation Starter: But for the Grace

In 2001, Memphis welcomed Sudanese refugee Emmanuel A. Amido. This year, he rewarded our hospitality with But for the Grace. The thoughtful film is a frank examination of race relations in America seen through the lens of religion. The Indie Memphis Audience Award winner sparked an intense Q&A session after its premiere screening that followed the filmmaker out into the lobby. It’s a timely reminder of the power of film to illuminate social change.

Best Comedy: What We Do in the Shadows

What happens when a group of vampire roommates stop being polite and start getting real? Flight of the Conchords‘ Jemaine Clement and Eagle vs Shark‘s Taika Waititi codirected this deadpan masterpiece that applied the This Is Spinal Tap formula to the Twilight set. Their stellar cast’s enthusiasm and commitment to the gags made for the most biting comedy of the year.

Best Animation: Inside Out

The strongest Pixar film since Wall-E had heavy competition in the form of the Irish lullaby Song of the Sea, but ultimately, Inside Out was the year’s emotional favorite. It wasn’t just the combination of voice talent Amy Poehler, Bill Hader, Lewis Black, Mindy Kaling, and Phyllis Smith with the outstanding character design of Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness that made director Pete Docter’s film crackle, it was the way the entire carefully crafted package came together to deliver a message of acceptance and understanding for kids and adults who are wrestling with their feelings in a hard and changing world.

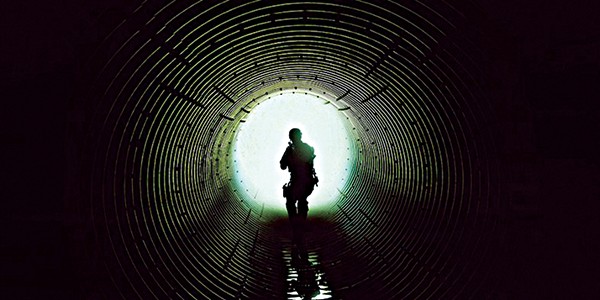

It Follows

Best Horror: It Follows

The best horror films are the ones that do a lot with a little, and It Follows is a sterling example of the breed. Director David Robert Mitchell’s second feature is a model of economy that sets up its simple premise with a single opening shot that tracks a desperate young woman running from an invisible tormentor. But there’s no escaping from the past here, only delaying the inevitable by spreading the curse of sex and death.

Teenage Dreams: Dope and The Diary of a Teenage Girl

2015 saw a pair of excellent coming-of-age films. Dope, written and directed by Rick Famuyiwa, introduced actor Shameik Moore as Malcolm, a hapless nerd who learns to stand up for himself in the rough-and-tumble neighborhood of Inglewood, California. Somewhere between Risky Business and Do the Right Thing, it brought the teen comedy into the multicultural moment.

Similarly, Marielle Heller’s graphic novel adaptation The Diary of a Teenage Girl introduced British actress Bel Powley to American audiences, and took a completely different course than Dope. It’s a frank, sometimes painful exploration of teenage sexual awakening that cuts the harrowing plot with moments of magical realist reverie provided by a beautiful mix of animation and live action.

Immortal Music: Straight Outta Compton and Love & Mercy

The two best musical biopics of the year couldn’t have been more different. Straight Outta Compton was director F. Gary Gray’s straightforward story of N.W.A., depending on the performances of Jason Mitchell as Eazy-E, Corey Hawkins as Dr. Dre, and O’Shea Jackson Jr. playing his own father, Ice Cube, for its explosive impact. That it was a huge hit with audiences proved that this was the epic hip-hop movie the nation has been waiting for.

Director Bill Pohlad’s dreamlike Love & Mercy, on the other hand, used innovative structure and intricate sound design to tell the story of Brian Wilson’s rise to greatness and subsequent fall into insanity. In a better world, Paul Dano and John Cusack would share a Best Actor nomination for their tag-team portrayal of the Beach Boys resident genius.

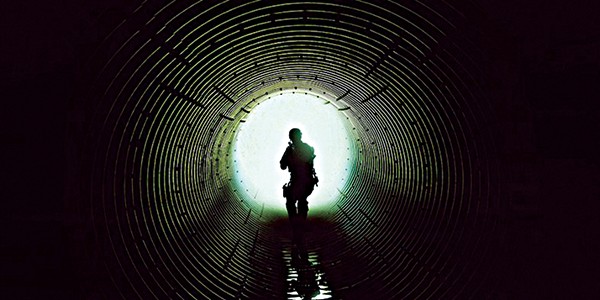

Sicario

Best Cinematography: Sicario

From Benicio del Toro’s chilling stare to the twisty, timely screenplay, everything about director Denis Villeneuve’s drug-war epic crackles with life. But it’s Roger Deakins’ transcendent cinematography that cements its greatness. Deakins paints the bleak landscapes of the Southwest with subtle variations of color, and films an entire sequence in infrared with more beauty than most shooters can manage in visible light. If you want to see a master at the top of his game, look no further.

He’s Still Got It: Bridge of Spies

While marvelling about Bridge of Spies‘ performances, composition, and general artistic unity, I said “Why can’t all films be this well put together?”

To which the Flyer‘s Chris Davis replied, “Are you really asking why all directors can’t be as good as Steven Spielberg?”

Well, yeah, I am.

Hot Topic: Journalism

Journalism was the subject of four films this year, two good and two not so much. True Story saw Jonah Hill and James Franco get serious, but it was a dud. Truth told the story of Dan Rather and Mary Mapes’ fall from the top-of-the-TV-news tower, but its commitment to truth was questionable. The End of the Tour was a compelling portrait of the late author David Foster Wallace through the eyes of a scribe assigned to profile him. But the best of the bunch was Spotlight, the story of how the Boston Catholic pedophile priest scandal was uncovered, starring Michael Keaton and Mark Ruffalo. There’s a good chance you’ll be seeing Spotlight all over the Oscars this year.

Had To Be There: The Walk

Robert Zemeckis’ film starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Philippe Petit, the Frenchman who tightrope-walked between the twin towers of the World Trade Center, was a hot mess. But the extended sequence of the feat itself was among the best uses of 3-D I’ve ever seen. The film flopped, and its real power simply won’t translate to home video, no matter how big your screen is, but on the big screen at the Paradiso, it was a stunning experience.

MVP: Samuel L. Jackson

First, he came back from the grave as Nick Fury to anchor Joss Whedon’s underrated Avengers: Age of Ultron. Then he channeled Rufus Thomas to provide a one-man Greek chorus for Spike Lee’s wild musical polemic Chi-Raq. He rounds out the year with a powerhouse performance in Quentin Tarantino’s widescreen western The Hateful Eight. Is it too late for him to run for president?

Best Documentary: Best of Enemies

Memphis writer/director Robert Gordon teamed up with Twenty Feet From Stardom director Morgan Neville to create this intellectual epic. With masterful editing of copious archival footage, they make a compelling case that the 1968 televised debate between William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal laid out the political battleground for the next 40 years and changed television news forever. In a year full of good documentaries, none were more well-executed or important than this historic tour de force.

Best Picture: Mad Max: Fury Road

From the time the first trailers hit, it was obvious that 2015 would belong to one film. I’m not talking about The Force Awakens. I’m talking about Mad Max: Fury Road. Rarely has a single film rocked the body while engaging the mind like George Miller’s supreme symphony of crashing cars and heavy metal guitars. Charlize Theron’s performance as Imperator Furiosa will go down in history next to Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven and Sigourney Weaver in Alien as one of the greatest action turns of all time. The scene where she meets Max, played by Tom Hardy, may be the single best fight scene in cinema history. Miller worked on this film for 17 years, and it shows in every lovingly detailed frame. Destined to be studied for decades, Fury Road rides immortal, shiny, and chrome.