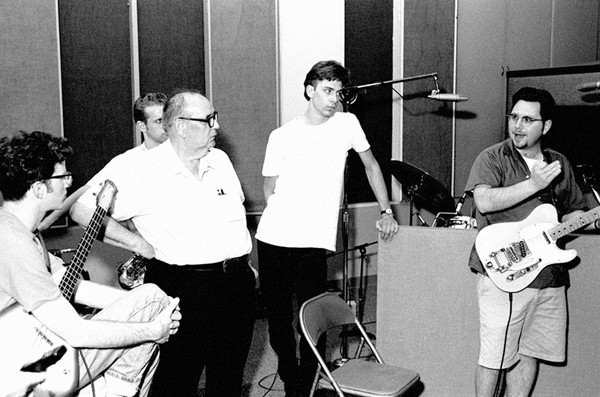

Last Friday, on February 9th, drummer James Mack Van Eaton, aka “J.M.” or “Jimmy,” passed away at the age of 86, and with him were lost some of the last first-hand memories of Sun Records’ early days. Any fan of Jerry Lee Lewis knows Van Eaton’s work, for on the day that Lewis showed up at Sun with his cousin, J.W. Brown, ready for his first proper recording session, producer Jack Clement called up Van Eaton and guitarist Roland Janes to fill out the band, and the rest is history.

As described in Peter Guralnick’s Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘N’ Roll, the ad hoc quartet cut over two dozen tracks that day. After they’d played themselves out, Janes took a bathroom break, then emerged only to hear Van Eaton and Lewis playing on as a duo, indefatigable. As it turned out, that stripped down drums-and-piano version of “Crazy Arms” was Lewis’ first hit for the Memphis label. And that was just the beginning, with Janes and Van Eaton going to to accompany Lewis on many of his hits. Ultimately, Van Eaton would record with several other Sun artists, including Billy Lee Riley, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, and Charlie Rich.

To reflect on the passing of one of Sun Records’ giants, I called on Sam Phillips’ son, Jerry Phillips, to share his memories of the man and his music.

Memphis Flyer: Did you know J.M. back in the day, when he was most active at Sun Records?

Jerry Phillips: I’ve known J.M. pretty much all my life. He started young at Sun and was I was young too, and over the years I’ve played with him and he’s played with me. You know, I was in Spain a couple of years ago at the Rockin’ Race Jamboree, a rockabilly festival. I started listening to the drummers, and you know, every one of those drummers was either trying to play like J.M. Van Eaton or they were playing J.M. Van Eaton licks. It wasn’t J.M. Van Eaton, but man, they were trying hard to be him.

He had quite a distinctive approach, didn’t he?

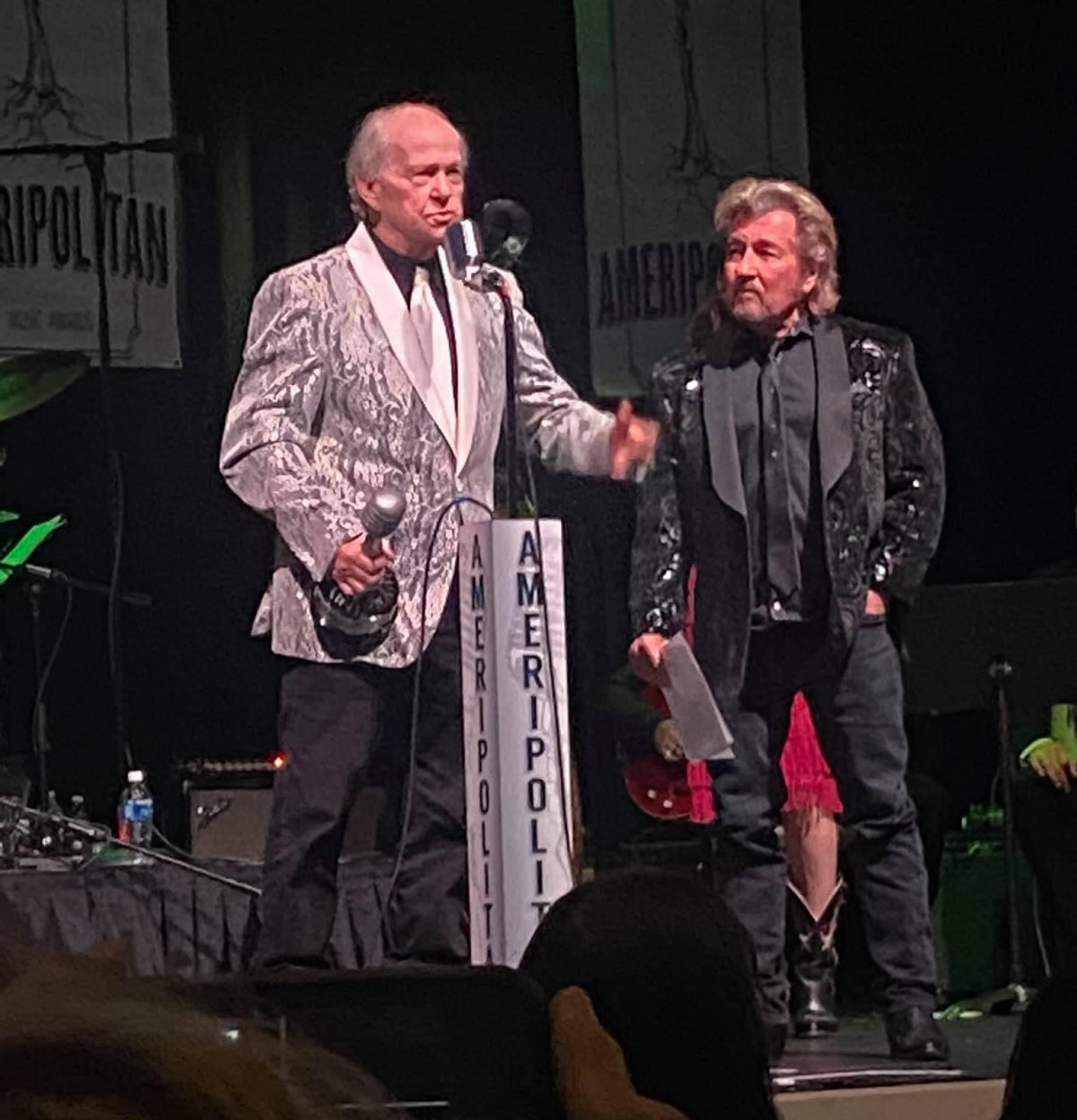

At the 2020 Ameripolitan Awards, J.M. got the Founder of the Sound Award, and they asked me to present it to him. In my speech I said, ‘I don’t know that Sun Records would have been the Sun Records it became without J.M.’s drumming.’ There was a definite sound that he had, and that’s what gave Sun a lot of its personality. I just don’t think we would have had the same sound or the same legacy had J.M. Van Eaton not been playing drums.

Just as my dad would say, ‘If you’re not doing anything different, you’re not doing anything at all.’ And J.M.’s drumming was completely different from anybody else’s that I’ve heard — except for the guys that are trying to imitate him. You never knew if he was going to do a roll, or what he was going to do. And he had that shuffle beat.

J.M. left full-time music behind for many years before coming back to the stage. Did he still have it when he got back in the game?

Oh, he definitely did. Probably 20 years ago, he brought a gospel group into the studio. And he played sessions with different people, just from kind of hanging around at Phillips Recording. Those guys that came out of Sun liked to just hang around. That’s what they did at Sun, they hung around.

Of course, you can’t leave Roland Janes out of the equation, either. Because J.M. and Roland were like a team. When Roland passed, they did a tribute to him at the Shell, and me and J.M. and Travis Wammack all got together and played.

J.M. eventually moved to the Tuscumbia/Muscle Shoals area and bought a house, and he always played quite a bit over there with different people. He played with Travis Wammack a lot. And I saw him and played with him more often there, since I was in the Shoals quite a bit because of our radio stations. We were better friends as adults, you know what I mean? And he just loved the Shoals area, and everybody there loved him.

He was just an extremely likable guy, wasn’t he?

I just can’t say enough about J.M.’s drumming, but also what a great person he was. I mean, I think he knew he was a great drummer, but maybe he didn’t. He never was one to say, ‘Hey, I’m a great drummer.’ But he just was. If you had J.M. on your session, you knew who was playing drums just by listening to him. And that was a signature Sam Phillips/Sun trademark, was that everybody over there sounded like themselves — and different. Tell me one drummer that J.M. sounded like!

Did you see or speak to J.M. soon before he passed away?

I did talk to J.M. the other day, I think it was a day before he passed away. We just had a little brief conversation. I told him how much I loved him and how important he was to everything. But he was pretty weak. He wasn’t really in the greatest shape, you know? Once his kidneys failed, he went downhill fairly quick. But up until that point, he was in pretty good health.

I’m gonna miss J.M. I really am. And I think J.M. was one of the most important people in the history of rock and roll music. I really do.

A celebration of life for J.M. Van Eaton will be held on Friday, February 23rd, at First Assembly Memphis, 8650 Walnut Grove Road, Cordova, from 6 to 8 p.m. A memorial service will be held at 1 p.m. on Saturday, March 2nd, at Cypress Moon Studios, 1000 Alabama Ave., Sheffield, Alabama. Call (256)381-5745 for details.

Cover artwork by Rui Ricardo

Cover artwork by Rui Ricardo  Dan Ball

Dan Ball