Last Saturday afternoon, the sharp screech of whistles blown by officials huddled in skates marked the start of Memphis Roller Derby’s (MRD) new season. The Pipkin Building in Liberty Park was abuzz with fans gathering in droves. As team skaters with star-stamped helmets whipped around the track — with serious grit — it was clear this league ran on more than adrenaline. They ran on community.

Community for the league looks different, depending on where you observe them. During their bout, the crowd’s hype elevated players to rock-star status, every lap earning an encore, each breakthrough met with a roar. When a skater known as “Don’t Blink” successfully broke through her opponents, the audience went crazy. Memphis was behind her — and she knew it, throwing a two-handed wave and a smile to fans as she rounded the track.

Family members and friends donned merch — some with the league’s name — while others opted for custom-made gear featuring their favorite skater’s face. Only some people sat in graffiti-sprayed chairs, the Pipkin Building well past standing-room-only. Derby was a big deal that day, but its importance goes beyond the bouts.

On a Tuesday afternoon prior to the game, the Pipkin looked a bit different. Skaters piled in for practice, and the indoor track seemed almost too pristine, too quiet — begging for a bit of edge that only chaos and passion can bring.

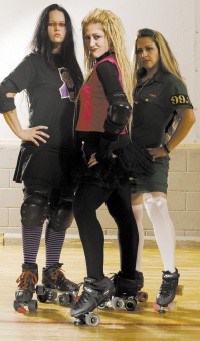

The MRD league has evolved since its start in 2006, with the sport getting more serious. (Photo: Chuck Ford)

As I eased into my first interview, the skaters moved from their pre-practice huddles into synchronized stretches. Their uniform side-to-side warm-ups transitioned into a high-energy sequence set to music. The beat blended into the background, and each players’ infectious swagger reverberated through the building.

Jemma Clary (known as Jem in the derby) lovingly refers to it as “off-brand Zumba,” led by their teammate Chandler. “It’s huge,” she adds. “It’s so fun because when we do it at games, other teams will sometimes join in. It’s always fun — hypes us up, gets our heart rates moving.”

From the energized warm-ups to the pre-scrimmage laughter, the camaraderie and community in the space was palpable. While the players’ individuality was reflected in their gear with sticker-covered helmets, when the digital “countdown to bout” clock ticked closer to zero, they shifted from individuals to one unit, from playfulness to determination. When the mouthguards go in, it’s game on.

Eye on the Star

“Pay attention to the person with the star on their head,” Clary tells me before the scrimmage round. “They’re going to be the one to watch. They’re going to be the one that’s scoring all the points for the team.”

I learn that the league prides itself on being a part of a niche subculture, one that stays alive partially through exposure to newbies. I’d only seen the sport on shows like Bunheads and The Fosters — usually as a shortcut to a character’s “edgy phase.” But that Tuesday’s practice was my first glimpse into the world beyond my streaming queues.

Clary translates derby in a beginner-friendly way, likening it to a mix of rugby, speed skating, and even a little bit of chess. She breaks it down as a game of jammers and blockers (the latter is the position Clary plays). The aforementioned star denotes the team’s “jammer” — the lead scorer.

“When we get out on the track, my job is to stop the other team’s jammer,” Clary says. “I want to keep them behind me. I do that by getting in their way and knocking them with my big ole butt, really. There are four of us that’ll be on the track as blockers and one person as a jammer. That’s for each team, so it’ll be 10 people on the track.”

A jammer must first get through a group of blockers before they’re able to score points by passing them.

“For every person you pass, you get a point,” Clary says. “It’s really easy to count points because you’re like, ‘How many people did they pass?’ That’s the big thing.”

Each team also has a “pivot” who wears a stripe on their head. The jammer can take their star off and give it to the pivot if they’re struggling to break past the other team’s blockers.

While popular culture is often people’s first introduction to the sport, Kendall Olinger (aka Choke) notes that these representations tend to conflate the sport to being “gimmicky” and akin to phenomena like wrestling.

The MRD league started here in 2006. “It’s evolved over the past 20 years to really stand alone as a serious sport with serious athletes,” Olinger says. “A lot of the stuff you see in the movies — or a lot of people bring up from watching roller derby from the ’70s or ’80s — it’s really gotten a lot more serious and way more focused on the sport. Lots of rules have changed, and a lot of those gimmicks have disappeared.”

Dylan Miller, an MRD jammer, says she didn’t know much about the sport aside from the 2009 film Whip It starring Elliot Page. Her journey beyond seeing derby on screen started at the league’s skate school in March 2023.

“I skated when I was a kid and I do think there was some ‘getting back on the bike’ type of thing,” Miller says. Through skate school she was able to master skills that she was “okay” at as a kid, like turning around and stopping. While these things may sound simple, Miller says the ingenuity of skate school is that it teaches and reinforces the basics of the sport to older audiences in a supportive environment.

“You’re getting lessons on all the basics and there’s somebody presenting the lessons, but you’re also getting one-on-one help from skaters in the league,” Miller says. “And we try to make sure it’s as accessible as possible to everyone regardless of their income.”

The league has taken this a step further by introducing Derby School, a program designed to refine their technique for derby readiness.

It’s been gratifying for Miller to see her growth from someone getting back on her wheels to joining the league. She notes it’s a “hard shift,” yet the league’s welcoming environment propelled her confidence. As a self-described “classic overthinker,” derby has given her the opportunity to get outside of her head and “leave it at the door.”

Don’t Blink

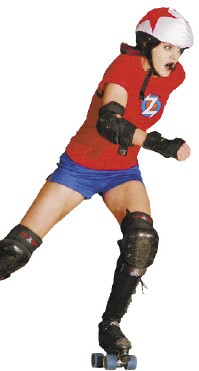

This transformation occurs in real time as Miller goes into bout mode, a conspicuous contrast from our pre-practice conversation. Miller takes a back seat, and “Dyl Pickle” takes over — one of the stars Clary told me to watch for.

On the track, Dyl is joined by the “other” team’s jammer “Don’t Blink.”

Prior to this moment, multiple players told me that Don’t Blink is a force to be reckoned with. Her name is a nod to her affinity for Doctor Who, a canonical yet witty reference to her lightning speed and prowess.

“‘Don’t Blink’ is like a warning,” Stacy Bautista tells me. “In the show, there’s a Weeping Angel statue and when you blink it comes to life and it’ll send you back in time and you die in the past. So, ‘Don’t Blink’ was kind of like a warning, like if you blink I’m going to hit you or come right past you — something bad is going to happen to you.”

She laughs at the irony of how her teammates sometimes shorten the moniker, calling her “Blink.” In some ways, it’s an inviting dare for opponents to see who they’re up against.

Aside from MRD, Bautista also plays for a borderless team called Fuego Latino Roller Derby. The league features a number of Latino skaters from across the globe, who will be playing in the Roller Derby World Cup in Innsbruck, Austria, this summer.

Bautista likens it to an Olympic-level derby competition composed of teams from all over the world. She reflects on her half-white and half-Cuban background, initially thinking there weren’t enough Cuban players to make a team that could play at the “World Cup level.”

“I was like, ‘the World Cup is not for me,’ because I don’t have the right background to get on a team and get to play,” she says.

But about two years ago, the borderless team was created. The team is not defined by country of origin but by culture. She adds that the goal was not specifically to be World Cup-bound, but an extension of efforts for skaters to form a community with people with shared cultural backgrounds.

Bautista was encouraged by MRD league members to apply, and with “help from a lot of people [in the league],” she was chosen for the World Cup Team.

“I’m super excited,” Bautista says, speaking of the opportunity. “The team has been really welcoming. When you’re only half-something, sometimes you don’t fit into either group very well, so both groups can be ‘you’re not really this or you’re not really that either,’ but a lot of my [Fuego Latino] teammates have that same kind of experience.”

Derby exists as a special place that invites interracial and intergenerational bonding, allowing skaters to build something “really fucking solid. It’s always an active thing,” Bautista says. “We try to create a space that is welcoming for all different backgrounds, who are inclusive of people who are also from other backgrounds.”

Why Skate

Beyond the requisite moxie, inclusivity seems to be an appealing tenet of derby culture. League members share that the search for community in adulthood can be surprisingly complex. Many found that the sport satisfies a hunger for togetherness, while also satiating the desire to achieve something real.

Bautistsa, for example, says that life after college graduation leaves much to be desired. For her, derby revives the thrill that sports like rugby and softball impressed on her while growing up.

“I loved a full-contact sport,” she says. “When you get out of college it’s like, ‘What now? You’re going to work a job and that’s it?’”

Initially that’s what her post-grad life led to — all work with little opportunity to meet people. She tried joining a book club for a minute but admits, “That wasn’t it. It was fun, but it wasn’t giving me the same connections to people.”

Ironically, it was through working as a carhop at Sonic that Bautista says the “roller derby seed” was planted. Yet, while derby was appealing as a return to the full-contact nature she grew to love, she was hesitant to go for it. A friend helped her overcome those initial jitters, and she’s now been engaged in the sport for 13 years.

“You’re playing offense and defense at the same time,” she says. “There are always new plays, people figuring different things out, people doing different footwork. It’s like a puzzle, but at high speed. You just keep leveling up.”

People like Bautista and Olinger note that the sport is appealing because it features full-contact play, but it also invites people to find community.

Similar to Bautista, Clary found the routine of working after graduation to be less than satisfactory. For her, post-grad life meant adjusting to her friends leaving Memphis and losing the community that college facilitates.

Clary says skating had “been her thing” since college, so enrolling in skate school was “something to do” as opposed to an introduction to the skill. And while she was looking for a way to pass time, she found a refreshing way to make friends in this new stage in life.

“I didn’t even come in wanting friends,” Clary says. “I joined and everyone’s just so friendly and welcoming. Roller derby is [also] like a pretty big queer space. I never really had fellow queer people around me, and it’s a lot of people that are older than me. It’s a pretty heterogeneous mixture of people, and people who are truly Memphians.”

These intergenerational spaces have proven to be invaluable. Not only does it contribute to league culture, but it’s what keeps the community thriving. The shared passion of skating permeates participants — both newcomers and seasoned skaters alike.

“It’s an honor to be able to skate with all these people,” Clary says. “I feel like over the past season we’ve been creeping up in the ranks and getting better and better, and everyone here who shows up regularly is super dedicated, not only to the sport but to the league and the community we have formed.”

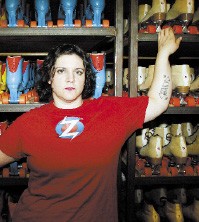

The league operates as a nonprofit driven and run by skaters and league members. Members like Bautista and Olinger are not only team members but work as the heads of training and marketing, respectively. Along with sponsors and community support, members and participants help keep the culture and sport alive.

“We all like [derby] but there’s more to it than that,” Olinger says. “We have a really supportive community. We all understand that we all have to work together, not just on the track, but off the track, too.”

Olinger recognizes this as a privilege, especially in “elective hobbies and activities.” And she says the league hopes to impress their emphasis on respect and togetherness not just on participants, but on the city.

Whether it’s through skate school or a bout, the skaters invite others to learn about derby. While each player may have a personal reason they keep returning to the track, they recognize their presence builds upon a legacy that lasts long after their wheels stop turning.

MRD’s next bout is the Home Double Header on June 14th at the Pipkin Building. Follow @MemphisRollerDerby on Instagram to find out about upcoming events.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks