It’s a well-known fact that Johnny Cash walked the line — and he had the size 13 boots to do it. That may not be the reason he wrote a song called “Big Foot,” but, regardless, Johnny Cash left some pretty large shoes to fill.In order to finish writing Hello, I‘m Johnny Cash, the first picture book for young people about the Man in Black, I knew I had to walk in his footsteps. I needed to put myself in those big boots of his, to feel the soil under my feet. I needed to head back to the beginning, to a place called Dyess, Arkansas — a town so small, it wasn’t on any map I saw. Even a good friend who lived about 45 minutes away in Memphis had never heard of it. So when the “highway” on my GPS turned into a dirt road, I knew I was on track.

Greg Neri

Greg Neri

The dirt road leading to Cash’s Dyess, Arkansas, childhood home

My first impression of the road leading into Dyess was a perfect Cash image: lonesome. It was so desolate, I could park my car in the middle of the highway, sit by a trickle of a river that weaved its way through the Deltalands, and never feel the urge to move the car. I could look in any direction as far as the eye could see and not spot a single living soul.

This was where Cash came from. An extreme landscape that had room enough for dreams to form but was tough enough that he had to fight to attain them. When I found his childhood home, a dilapidated house with a few bare trees, it was no Graceland. I stepped onto the gravel and was hit by the wind sweeping off of the endless horizon. It actually howled.

Greg Neri

Greg Neri

Cash’s childhood home

The home seemed old and uncared for. There was a metal sign that made this monument to the man official, but the place itself was far from being worthy of his name (though that would soon be rectified). I walked around the property, alone. It seemed odd that on this day, the day of his birth 80 years ago, nobody would be here. Where was the parade, the ribbon cutting for this giant of a man? It seemed far away at the moment.

When I stepped onto the fields surrounding his house, I felt an immediate connection to young J.R. (as he was known in those days). My boot sank ankle deep into the mud, and when I attempted to extract it, only my bare foot emerged. The shoe and sock remained stuck in this gunk he’d called gumbo. Now I knew why. I realized why his father had to stop the truck far from the house when they first arrived back in 1935: it would go no farther in this gumbo. I couldn’t imagine what it took to clear this land of thickets and boulders and scrub oak to turn it into cotton.

Greg Neri

Greg Neri

The ‘gumbo’ muddy sludge Cash referred to in the fields surrounding his Dyess home

Little details like that ground a story. I imagined 5-year-old J.R. sitting on the porch as his family picked cotton in the fields, listening to the classic train song “Hobo Bill’s Last Ride” on his small battery-powered radio. One of his earliest memories was of his father jumping off a train in front of their old home in southern Arkansas. Unlike Hobo Bill, they’d survived the Great Depression — barely — and began eking out a meager life in a New Deal farming community that was opened by Eleanor Roosevelt herself.

But being a cotton farmer was hard work, and as I stood there in the harsh winter sun, stuck in the mud with my face sandblasted by the wind, I could see why J.R. might spend so much time escaping this harsh reality for one filled with music from faraway places.

I ambled down a long, empty road that led to the town of Dyess. It took a good hour. Empty fields lined both sides of the road and a dead, dark creek sat alongside. A vulture or hawk circled high overhead waiting to see if I was going to make it to town.

This was the road J.R. had followed in the pitch-black night, singing to himself to ward off the growling wildcats. There was the fishing hole where he heard the news from his father that his closest brother, Jack, had been sucked into a circular saw and was close to death. There was the shack where he’d first heard a crippled boy playing guitar as good as Jimmy Rodgers and then asked the boy to teach him to play. Every detail came to life.

The community of 402 townsfolk had a small circle with a flagpole planted in the middle. Surrounding that was a partially destroyed theater, an old community center, a gas station/café, and a high school. J.R.’s school. Just as when J.R. had seen his radio heroes, the Louvin Brothers, perform for the first time at his school auditorium, something very special was happening this day in the same building: The extended Cash family was gathering from all over to celebrate what would have been Johnny’s 80th birthday.

Greg Neri

Greg Neri

The event wasn’t advertised or Tweeted. You couldn’t buy tickets because they weren’t for sale. I’d seen a small personal mention of it through my research and knew I had to go. Rosanne Cash was going to be there, and by coincidence, a friend of a friend knew her manager and I had an in. It was a family reunion: Johnny’s brother Tommy, his sister Joanne, and his children — John Carter, Kathy, Cindy, and Tara were all coming. As I sat in the parking lot waiting for everyone to arrive, I slowly became aware that I was an outsider. My first clue was from an Arkansas State Trooper wearing a big hat, mustache, and mirrored sunglasses who leaned over me and said: “You ain’t from ’round here, are you?” I played friendly though, and as soon as he heard I was from Tampa, stories of his cousin came bubbling up and all was good.

People started arriving — nephews, nieces, cousins, second cousins, friends from back in the day, about 100 Cashes from the extended clan, some locals … and me. A smattering of small-town media and a few folks from Arkansas State University milled about, recording and helping with the event. Family mingled, most looking country; one — a niece, looking lost, like she’d wandered off the pages of teen Vogue: black mini dress, hoop earrings, and navigating the gravel in high heels. Johnny’s surviving sister, Joanne, spotted the original family piano that her mother played back in the old house and started tinkling on it. I gazed at old family photos blown up and framed for the gathering. Rosanne’s manager saw me and took me to a back room where Rosanne and John Carter were busily going over last-minute notes. A show was about to begin.

Greg Neri

Greg Neri

A 1949 Cash family photo

It was thrilling to see the immediate family take the stage. This could have been a big media event but it was more reminiscent of an old Carter family barn stomp. It felt homey and right, and I was honored just to witness it. The family traded licks on folk and gospel songs from that era, and then joined together to sing some of Johnny’s songs about cotton and mud and the Flood of ’37.

There was much talk of the restoration efforts being made to save Johnny’s boyhood home. If done right, it would save the town as well.

Author Greg Neri with Johnny’s daughter Rosanne Cash

When Rosanne introduced me to her sisters by saying “he’s writing a book about daddy growing up here,” their eyes lit up; that alone was worth the trip.

I left that gathering floating on air, much as J.R. did when he saw his radio heroes come to life. But I quickly came back to earth. I was heading out for a more remote and heartbreaking location: the grave of Johnny’s beloved brother, Jack. The death of Jack Dempsey Cash probably haunted Johnny the rest of his life. Not a day went by where he didn’t think of his brother or ask himself ‘what would Jack do?’ Jack’s tragic death and its effect on his brother’s life became the spine of my story. His grave was a necessary stop.

I assumed the family would probably go and pay their respects, but I wasn’t prepared for how isolated and lonely the place felt. There was no one there, no signage that there was even a cemetary. Tombstones just appeared along the side of the road. I wandered for a while, until I stumbled across Jack’s small tombstone. I imaged Johnny digging the grave on a warm spring day back in 1944. Not only was he heartbroken and dirty during the service, but his foot swelled up from stepping on a rusty nail. Still, he sang Jack’s favorite gospel songs before they had to return to the fields to work the next day. I righted some old plastic flowers that seemed like they’d been there forever and quietly walked away.

When Johnny Cash left Dyess at 18, he joined the Air Force and was stationed in Landsberg, Germany. But when he returned home, with a new bride in tow, he settled in Memphis, Tennessee, where I was heading next. “I’m going to Memphis,” Cash famously sang. Memphis, Tennessee, birthplace of rock-and-roll and the city where Johnny Cash became a star. These roads were paved, not with gold, but with cement and asphalt.

The first place I stopped was the first stop Johnny made when he arrived: his brother Roy’s workplace, the Automobile Sales Company on Union Avenue. It appeared deserted. There was no placard marking the historic meeting that occurred on that day back in 1953. This was the spot where Johnny’s music career really began, because it was here that his brother introduced him to two mechanic friends who later helped create that famous boom-chicka-boom sound: Marshall Grant and Luther Perkins. On this day, all I heard was the traffic passing by, drivers unaware of the significance of this closed-up building.

My next stop wasn’t far and turned out to be an empty parking lot with an arrow pointing over an empty sign frame, as if to say this spot was important. The first job Johnny had out of the Air Force was at the Home Equipment Company on Summer Avenue. He made for a lousy door-to-door salesman, preferring to listen to his car radio instead. But it was his boss who knew he had talent for singing, not for selling, and loaned him money to pursue his dream, even sponsoring a small-time radio show featuring Johnny and the Tennessee Two. Without that support, Johnny might’ve high-tailed it back to Dyess or signed up for another round of active duty.

Wandering around this industrial area of town seemed far from the honkytonks and blues clubs on Beale Street. I could feel his frustration on this stretch of used car lots.

My next stop was in a hipster neighborhood on Cooper Avenue, at the old Galloway United Methodist Church. What happened in its basement was a major event in music history. After playing at Grant’s or Perkins’ house for months, the boys decided it was time to perform in public. The only problem was they couldn’t convince any club that they were good enough, especially with their hillbilly music. But a friend asked them to perform some gospel music in a basement at Galloway Methodist.

Johnny loved gospel, so it seemed like the right place to start. Having no proper clothes for a band, they decided to wear the only matching color they had: black. Thus, the Man in Black was born. Funny how accidents can change the face of music.

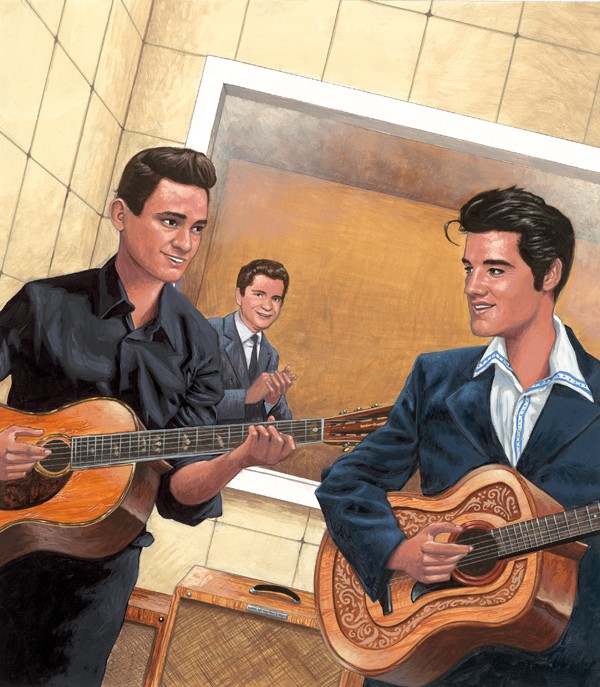

I then made my way over to another parking lot behind a Save-A-Lot store. It was mostly empty, except for a man washing his car. He probably had no idea that on this very spot at the Lamar Airways shopping center, 21-year-old Johnny Cash first met a country boy named Elvis Presley, who woke him up to a new sound that would take the world by storm. It was supposed to be just a drug store opening with a band on a flatbed truck. But with 19-year-old Elvis singing, Johnny witnessed a hoard of screaming girls and the pulsating music that drove them into a frenzy. He knew that’s where his future lay. He and Elvis became friends. The next day, Elvis told him about his producer, a guy named Sam Phillips over at Sun Records.

If there’s one spot people know about Johnny and Memphis, it’s Sun Records. Here Johnny ambushed Phillips in the parking lot and convinced him to listen to his music. He played gospel and folk, any song he knew from the radio. But when Sam asked him to play something he wrote, Johnny sang “Hey, Porter,” and history was made. Within months, the birthplace of rock-and-roll would produce Elvis, Johnny, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison. To stand on the spot in the studio and hold the very mic into which Johnny sang “I Walk the Line,” made his whole story seem real.

A.G. Ford

A.G. Ford

It was a do-or-die moment for Johnny, because he had run out of money and had a daughter (Rosanne) on the way. Right before he cut his first record, his wife Vivian gave birth, and they moved into a duplex on Tutwiler Avenue. Driving by it now shows how much Memphis has changed. The house remains very much as it was. You can imagine Johnny sitting on the porch, strumming his guitar as he wrote the B-side to his first record, “Cry Cry Cry.” But today, it’s a poor neighborhood, far from the suburban block it used to be.

Author Greg Neri holding Cash’s microphone at Sun Records

I went back to Union Avenue to see where the first Johnny Cash song was ever played on the air. Sam asked Johnny to run the first pressing of his single over to WMPS radio, where it would be played live. He watched that golden Sun label spin around as “Hey, Porter” went out over the airwaves. But when the DJ flipped the record, it slipped and broke on the floor. Johnny thought it was the only copy and was devastated until Sam pulled out a box of them.

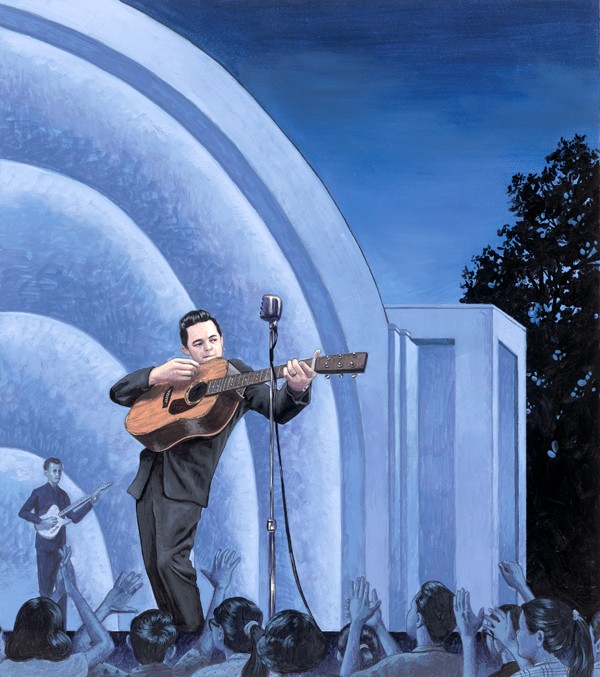

My final stop at sunset seemed frozen in time. I stood on the stage of the Levitt Shell amphitheater and gazed out at the grassy slope surrounding it, picturing it filled with Memphis teens in their 1950s’ best, plus all of Johnny’s family and friends who’d turned out to see him open for Elvis. It was the first time anyone saw the true power and magnetism he had as a performer, even giving the future King a run for his money. He sang his only two songs, electrifying the crowd so much, they kept calling him back for more. After singing those songs twice more, he pulled out a new one. It was the first time he’d perform the classic that would define his music personality: “Folsom Prison Blues.”

A.G. Ford

A.G. Ford

I stood there for a long time, marveling at the journey this 23-year-old man had taken from the son of a cotton farmer to music legend. Only 55 miles separated the world of cotton and mud he grew up in and the heyday of Sun Records and rock-and-roll, but it might as well been two different planets. As the sun set and the stars came out, I couldn’t help but wonder at the thrill he surely felt when the crowds wouldn’t let him leave. Standing in his shoes, I could feel the country boy grinning at his good fortune — and a wide open future.

Greg Neri‘s illustrated children‘s book, Hello, I’m Johnny Cash, will be available in September.

HELLO I’M JOHNNY CASH. Text copyright © 2014 by G. Neri