In honor of the Flyer Flashback page that’s been running in the Flyer this year, here’s a history of the Antenna Club that Ross Johnson wrote for a cover story in October of 1997.

Til The Well Ran Dry

A selective history of memphis’ original punk club.

by Ross Johnson

The plain-looking bar at 1588 Madison has been known variously as the Mousetrap, Detroit Rock City, Good Time Charlie’s, the Well, Antenna, the Void, Barristers, and currently as Madison Flame. In its incarnations as the Well and Antenna, it served as a backdrop for the development of Memphis’ punk/underground music scene. From 1979, when the Well opened its doors, until 1995, when manager Mark McGehee closed the Antenna Club, this site produced an endless variety of noise and musical aggravation. That such a scene developed out of a Midtown watering hole is an interesting story. That it thrived and persisted for 16 years is an even stranger one.

In 1978 the bar was known as Good Time Charlie’s and owner Frank Duran featured live music after hours from Memphis bands like Crawpatch, but in early 1979 he changed the club’s name to the Well and began featuring local rock bands on weekend nights. In February of that year local pop-rockers Hero (featuring soon-to-be Crime drummer Carlton Rash) had a Friday/Saturday booking there. Randy Chertow, bass player for the Randy Band, went down that Friday night to check out the club as a possible site for his group.

Hero did not draw much of a crowd that evening, but Chertow liked the club and wanted a booking as soon as possible. To speed up the process, he called the next afternoon, saying he was an agent from New York City with a band needing a place to play that Saturday night. When the conversation ended, the Saturday-night bill at the Well featured Hero and the Randy Band. This event marked the beginning of the punk scene in Memphis.

Previously, vaguely punkish groups like the Klitz, the Scruffs, and the Randy Band made do with bookings anywhere they could get them, usually misrepresenting themselves as kickass rock groups to club owners who wanted only cover bands who could draw drinking crowds. Any group that was arty or that played original tunes was less than welcome on most Memphis club stages. Frank Duran didn’t care about any of this; he simply wanted customers for the Well. And the Randy Band provided that on a regular basis with weekend bookings there.

The Randy Band was largely responsible for pulling the strands of Memphis’ burgeoning underground music scene together at that time. Singer/guitarist Tommy Hull and bass player Randy Chertow met in 1976 and began playing in local clubs as the Randy Band in 1977. Chertow cites early Memphis pop-rockers the Scruffs as inspiration and competition, but the Scruffs left Memphis for the New York scene in 1978, discouraged with the lack of live music outlets in Memphis for any band that didn’t play boogie or metal.

The Randy Band played Uncle Ernie’s, the Cosmic Cowboy, Prince Mongo’s, the Oar House, the Midtown Saloon, and even numerous times in the pub at Rhodes College. But it was at the Well that they found a sympathetic, interested audience, consisting mainly of teenage girls and friends of Chertow’s, who was an expert at getting the most unlikely people together in social and musical situations.

By 1979 the group consisted of Chertow, singer Hull, guitarist Ricky Branyan (formerly of the Scruffs and glad to be back in Memphis), and a number of drummers that came and went. With Branyan’s boyish good looks, Hull’s expertly crafted and catchy pop songs, and Chertow’s melodic bass playing (people often joked that the Randy Band had two rhythm guitarists and a lead bass player), the band started pulling good crowds with regular weekend bookings at the Well. People still speak of those early Well performances in glowing terms; it is a shame that the Randy Band’s sound was never adequately documented on vinyl (this was before CDs, folks). But they did start things rolling at the Well, soon attracting the attention of other Memphis bands desperate for a new place to play.

Tav Falco’s Panther Burns had just formed in early 1979 and were looking for somewhere besides a cotton loft on Front Street to play. Falco’s crew noticed the rather large crowds the Randy Band was drawing and wanted to be a part of that scene. They also noticed the growing numbers of teenage girls attending Randy Band gigs, but that’s another story.

So the Burns and the Randy Band started sharing weekend dates at the Well. During this period Duran would occasionally pull the power on the Panther Burns when they got particularly noisy and unmusical (which was pretty often in 1979). Duran had no problem ejecting unruly drunks from his club or offensive musicians from the stage. He would always let performers know when they had gone too far and if they didn’t quit then, he would make them stop one way or another.

Memphis all-girl band the Klitz, got in on these Randy Band/Panther Burns bills too. The Well was very much a drunken social club in those early days, with band members swapping out both musically and sexually, quite a lot like other developing punk scenes across the country at that time.

The Well gave the Memphis scene something of a working-class orientation to go along with the expected dose of drink, drugs, noise, and excessive emotionality. Older regulars from the Good Time Charlie’s/Mousetrap days still hung out at the bar in the afternoons for cheap beer, and if they got particularly drunk they would often stay for the band sets on Friday and Saturday nights. Band members were often treated to impassioned critiques of their estimable musical talents from the happy-hour regulars who were too drunk to get off their bar stools and crawl home. Some of the Well musicians also started dropping in early to drink and debate with the older crowd who came in during the afternoons. A number of unlikely friendships between redneck barflies and punk-rock irregulars developed during those foggy happy hours.

When the legal drinking age in Tennessee changed from 18 to 19 in 1980, the problem of underage drinking raised its head. The police started making regular late-night raids at the Well checking for underage drinkers. More than once Duran came close to losing his beer license.

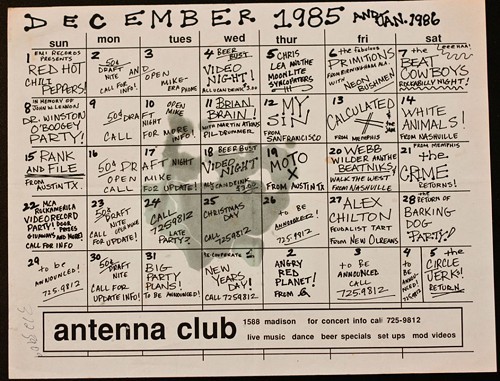

Tiring of the aggravation, he decided to sell his interest in the club to local hair stylist Jimmy Barker, who wanted to turn the Well into more of an arty new music club. With financial backing from Phillip Stratton, Barker opened the Antenna in March 1981 with a show featuring Memphis’ Quo Jr. and rockabilly trend-jumpers the RockCats (at the time featuring New York Dolls drummer Jerry Nolan).

Plastic forks hung from the ceiling (the health department later made Barker take them down); the walls were painted black; the mirror behind the stage was gone (a memento from the bar’s earlier tenure as a strip club); and there were television monitors showing what soon came to be known as “videos.” Barker’s videos featured himself and a number of his friends dryly emoting in front of a static video camera. From March 1981 until the Antenna closed, the bar featured these monitors which were turned on immediately after bands played; those flickering images were often on during bands’ live sets as well. This practice had a disconcerting effect after a while, especially when one of your favorite bands finished a set and a Duran Duran video came on immediately afterward. Many people got their fill of rock videos at the Antenna long before MTV killed off popular interest in the form. But it was one of those things you got used to if you spent any time there.

BARKER CHANGED MORE THAN JUST THE look of the club; he booked national acts at the Antenna. Previously the Well had featured Memphis bands exclusively, allowing a rather fragile scene to develop musically and commercially without competition from out-of-town groups.

A few weeks after the Antenna opened, Barker booked the Brides of Funkenstein, who put on an extravagant show, the likes of which most Well customers had seen only on television or in live concerts at larger halls.

Of course, Barker lost money with this practice, and soon partner Phillip Stratton was looking for someone else to help him with the more mundane aspects of club management. Enter Steve McGehee from Frayser.

McGehee, who had worked for a number of years at TGI Friday’s, was looking for a club to manage. Barker was forced out rather abruptly and McGehee took over the day-to-day operations of the club in June 1981 with Phillip Stratton remaining a partner until 1984, when McGehee bought him out. The Antenna remained McGehee-family-owned and -operated until it closed.

McGehee booked a combination of local bands along with national and international acts. He recalls using Bob Singerman’s New York-based booking agency a lot in the early days. More often than not, agents would call him with a group they wanted to book at the Antenna.

As the years went by, McGehee saw more contracts and riders from the out-of-town acts that appeared there. When the Irish group Hothouse Flowers played, he had to add some extra stage planking to accommodate a rented grand piano they insisted on having; he had to have the piano tuned as well. German noise-rockers MDK played the Antenna in 1983 and insisted that Steve provide a meal, shoving a copy of their contract in his face and saying,”McGehee, feed us.” He obliged with a few of “Burrito Bob” Holmes’ special burritos that were languishing in a freezer in the club’s little-used kitchen. They ate them greedily and in appreciation flooded his bathroom and stole several pairs of blue jeans after they stayed at his house.

The Antenna became a regular stop for SST record-label bands in the early to mid-’80s. Black Flag played there numerous times with Henry Rollins before he turned into a professional careerist and self-promoter. Word of mouth played a part in bringing national groups to the Antenna. Touring bands would tell other groups that the Antenna was the best place (or only place) to play in Memphis.

In 1991, McGehee produced T-shirts to commemorate the club’s 10th anniversary. On the shirts was a list of every band that played the Antenna during that period. McGehee compiled the list from booking calendars and memory. Looking at that list now one sees the names of groups that have gone on to sell millions of records as well as obscure loser bands that played once and then broke up.

R.E.M. played the Antenna several times. The band once called Tav Falco to see if the Panther Burns would be interested in opening for them. Falco, who had never heard of them, passed on the offer.

Davis McCain’s (of Easley Recording) band Barking Dog took that opening spot and even supplied the PA which R.E.M. blew that evening. Those were the days before Michael Stipe and his boys became college favorites, and they often played in an intoxicated state on stage. By the time their first IRS album was released in 1983, they were pulling crowds too large for the Antenna to accommodate. But Steve McGehee had them first and their recently fired manager, Jefferson Holt, used to take the door for them, even lending beer money if you were broke and particularly desperate for a beer.

THE CLUB DEPENDED ON LOCAL bands for the most part, of course. The Crime and Calculated X were big draws in the early ’80s, peddling Memphis versions of power pop and British synth rock respectively. Hipper bands may have looked down on these two, but they also envied their ability to fill the Antenna to capacity. The Panther Burns waxed and waned in their drawing power over the years at the Antenna.

“You either hated or loved the Panther Burns,” McGehee says. “They were either really good or really bad. There was no in-between with them. The same was true of the Modifiers.”

Probably no other Memphis band personified the Antenna better than the Modifiers. The core of the group was singer Milford Thompson and guitarist Bob Holmes with second guitarists, bass players, and drummers coming and going. They played a brand of music that could best be described as a cross between Ferlin Husky and Black Flag years before the current interest in bands that rock up country sounds.

Unfortunately for them, the Modifiers were ahead of their time, and after an extended period in Los Angeles in the mid-1980s, they broke up.

“People would get mad at me for always booking the Modifers as an opening act, but I didn’t have to pay ’em anything,” McGehee recalls. “They played for beer. They would show up at noon for soundcheck and by 5 p.m. they would be so drunk they could barely see.”

The Antenna was more than just the bands that played there. Steve’s sister, Robin, tended bar in a cheerful manner and served countless drunks who never stopped trying to pick her up.

The Antenna had a reputation as a violent club, but in reality there were few fights in the bar, quite a feat when one recalls the sheer volume of drunken Memphians who came to the club for the express purpose of “punkin’ out.” Rebel from Frayser took money at the door and always had a good story for anyone who cared to listen. And finally, there was broken-hearted Rowena (immortalized in a Modifiers song of the same name) who sat at the bar night after night looking for a kind word or gesture.

In 1988, the state of Tennessee assessed McGehee a rather large amount in unpaid sales taxes, effectively keeping the Antenna in perpetual bankruptcy until it closed. No matter what resentful musicians may have thought at the time, McGehee did not make a fortune running the Antenna.

“I lost more than I made,” he says. “I promise you that. A lot more.”

McGehee married in 1988 and started a family, putting a further financial strain on his situation. He recalls that on St. Patrick’s Day 1991 he was ready to close the club down, but he asked his brother Mark if he would take it over for him. Mark McGehee stayed on until the Antenna closed.

Mark had to scramble for bookings while local groups played at the New Daisy and other Memphis venues. Steve recalls that Club Six-One-Six seemed to take away a lot of his business after it opened with a similar format as the Antenna.

By June 1995 the brothers McGehee, tired of the struggle, decided to sell the bar. It reopened later that year for a brief period as the Void, and former Barristers owner Chris Walker ran it as Barristers Midtown for a few months during the spring of ’96. Currently the club is known as the Madison Flame. Local bands appear there on an irregular basis.

Essentially the club’s history came to a halt in 1995 when the McGehees threw in the towel.

“It got to be more of a hassle trying to pay off the back taxes than it was to keep it open. I only regret that more people didn’t hear and see the stuff I did there because there was some incredible music that happened in that place,” Steve McGehee says today. “I remember many nights when I was in there by myself seeing great bands and saying I can’t believe there’s nobody here to see these people. Now there were also a lot of times when I wished I wasn’t there. But great bands would come and go and nobody would ever know it.”

And what ever happened to Barry Bob anyway? (Ross Johnson was a drummer with Panther Burns. His retrospective on that band appeared in the February 1-7, 1996, issue of the Flyer.)

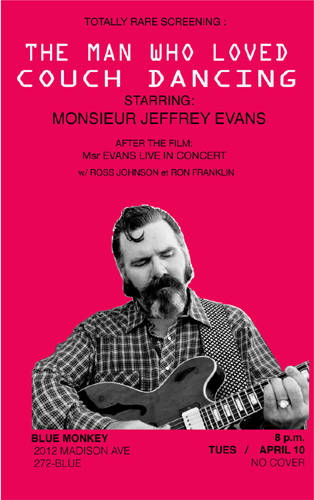

Courtesy of Goner Records

Courtesy of Goner Records