Hollywood is not exactly a place where justice flourishes. But aside from all of the sexual assault, and the way some white guys keep failing upward, one of the biggest injustices in Hollywood is the fact that there is no Academy Awards category for stunt work.

I don’t know if you’ve looked at a movie lately, but stunt performers are getting more screen time than ever. Many great pioneers of cinema built their reputations on hair-raising stunts: Think Charlie Chaplin roller-skating backwards on the edge of an abyss in Modern Times, or Buster Keaton riding on a locomotive cow catcher, batting railroad ties off the tracks in The General. Jackie Chan, the king of the Hong Kong stunt performers, has broken so many bones his injuries were shown as outtakes in his film’s credit sequences. Chan’s pain became part of his star attraction.

It’s not like stunt work is not artistic. Look at the greatest film of the 21st century, Mad Max: Fury Road, and tell me the pole cat attack, where the performers are swinging on 20-foot poles mounted on vehicles traveling 80 miles per hour, is not artistic. Even if you do define “art” more narrowly, there’s still the existence of technical categories like Best Sound Design and Best Visual Effects. Stunt work is every bit as necessary for the success of the film as the talented professionals in those categories.

And look, if you want to jazz up the rating of the Academy Awards (and who doesn’t want jazzier ratings?), adding categories where Mission: Impossible and Fast & Furious could win something is just the ticket.

One person who definitely agrees with me on this, the most pressing issue of our time, is director David Leitch. He’s a former stunt performer himself, having been at one time Brad Pitt’s stunt double of choice, before directing the star in Bullet Train. He’s also the co-creator of the John Wick franchise, which has taken fight choreography into the realm of modern dance. The Fall Guy is his love letter to the world of stunt performers. It’s the rare action movie that really feels like it’s made with love.

It’s also relentlessly inside baseball because there’s nothing film people like more than films about themselves, or “self-reflexivity” in film theory-speak. The Fall Guy is ostensibly based on a TV series from the 1980s starring a post-Six Million Dollar Man Lee Majors as a stunt man who solves crimes. (In the 1980s, it was a requirement that every TV star had to solve crimes. But I digress.) In a weird way, The Fall Guy owes a great deal to Francois Truffaut’s Day for Night, the 1971 romantic comedy about a film set that’s always on the verge of falling to pieces but never quite does.

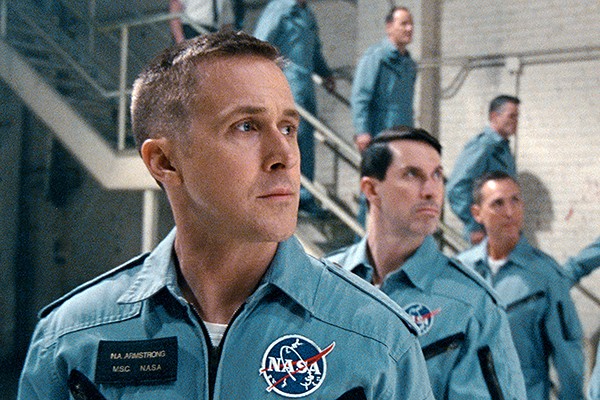

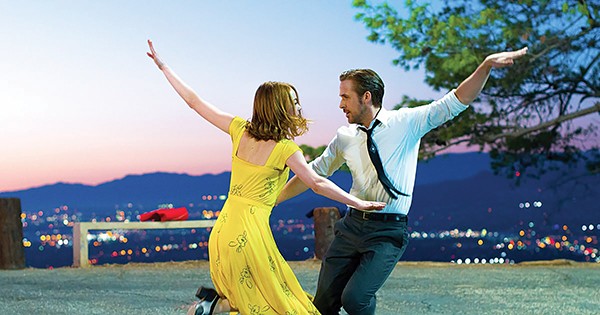

Leitch’s star is Ryan Gosling, and to say he’s perfect for the role of Colt Seavers is a profound understatement. The source material is a notoriously rich vein of Reagan ’80s masculinity, with Majors driving a truck and singing country music between bringing in bounties. Gosling brings some much needed Kenergy to the role. This Colt Seavers cries to Taylor Swift songs. There’s not too many actors who could convincingly make a phone confession of their love to their girlfriend, director Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt), while also fleeing from assassins in a stolen speedboat.

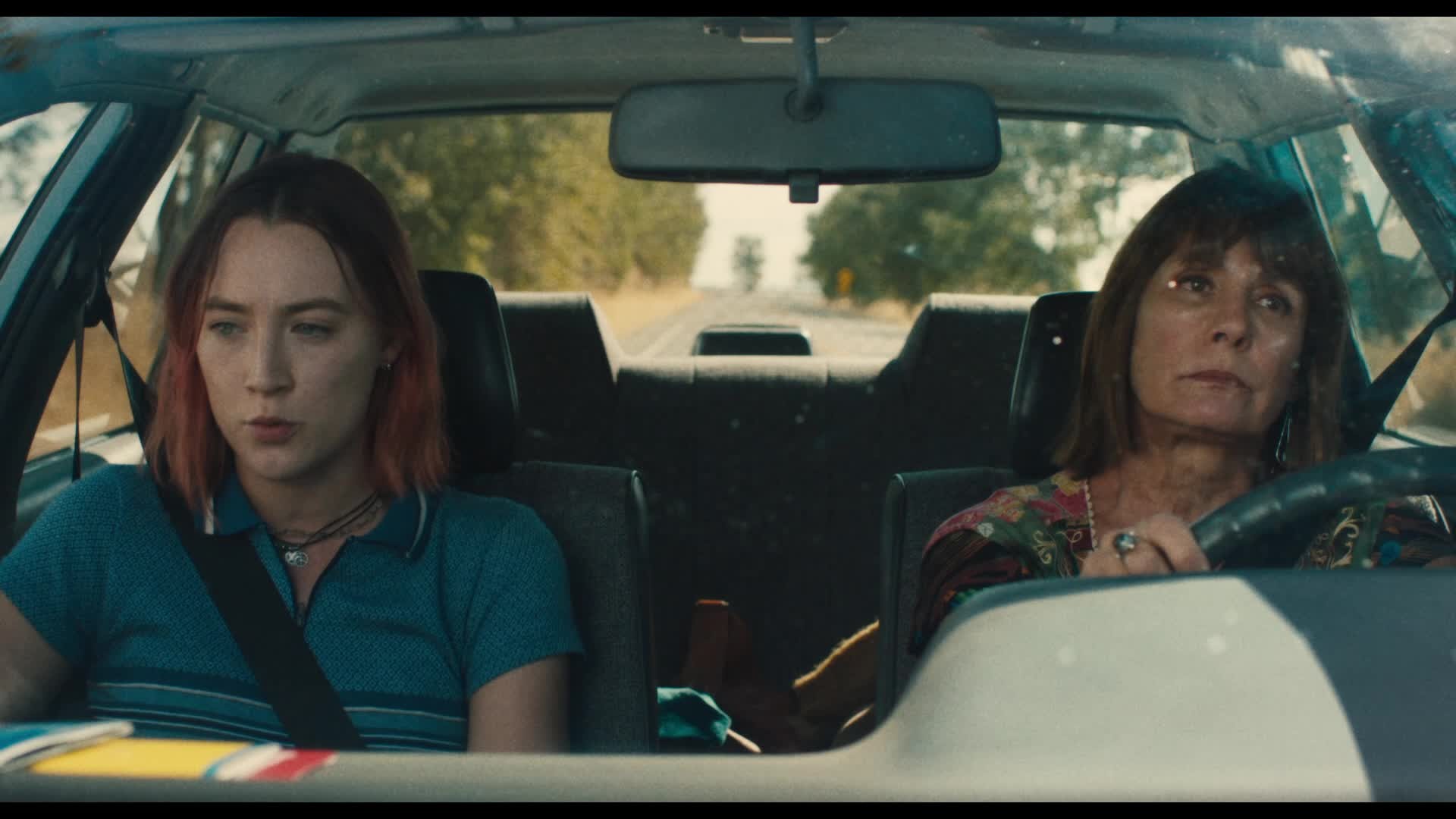

Jody and Colt met years ago when she was a camera op and he was the preferred stunt double for megastar Tom Ryder (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). While filming Tom’s latest sci-fi blockbuster, their relationship evolves from a semi-recurring, on-set fling (which is a fairly common thing in the film world) to something more serious. Then, producer Gail Meyer (Hannah Waddingham) insists Colt do another take of a dangerous high fall. Colt’s luck runs out, and he wakes up on a stretcher with a broken back.

Eighteen months later, Colt is hiding out in Los Angeles, working as a valet at a Mexican restaurant, when Gail catches up with him. Jody is directing her first big feature film, a passion project she and Gail have worked for years to put together. They need Colt for a big stunt, a dangerous cannon roll on a beach. Jody has personally asked for him, Gail says, to support her as she tries to make good on her first big break. More inside baseball: Jody’s “passion project” is apparently a remake of the 1983 movie Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn, a 3D debacle so notoriously awful it is nowadays only watched by sick cinematic masochists such as myself.

Colt arrives on set in Sydney and pulls off the spectacular stunt, which in real life broke the Guinness World Record for most on-screen rolls by a car — a fact the film-within-a-film’s stunt coordinator Dan (Winston Duke) points out. But Jody’s not happy to see Colt. She was crushed when he cut off contact after the accident, and tells him via bullhorn as she repeatedly sets him on fire. “That was perfect! Let’s do it again!”

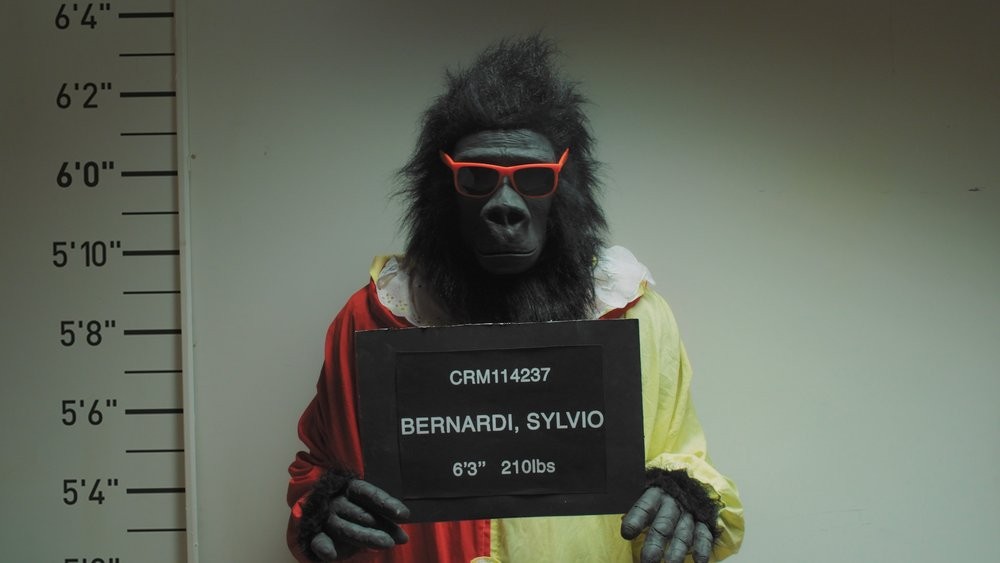

When Colt confronts Gail, she reveals the real reason he’s been brought on board. Tom Ryder has gone missing, and since he and Colt used to be tight, Gail thinks he would be the best at discreetly tracking down the wayward movie star before Jody and Universal Pictures find out he’s gone AWOL.

Gosling and Blunt are breezy and charming, and the supporting cast all understand the assignment. The whole point of the now-forgotten TV series was to cut to the chase, forget about all those pesky story beats, and get to the good stunts. The Fall Guy is at its best when it’s putting its small army of crack stunt performers through their paces with the safety wires and crash bags fully visible for once. It only makes the stunts more harrowing by emphasizing the human frailty of the performers.

The Fall Guy

Now playing

Multiple locations