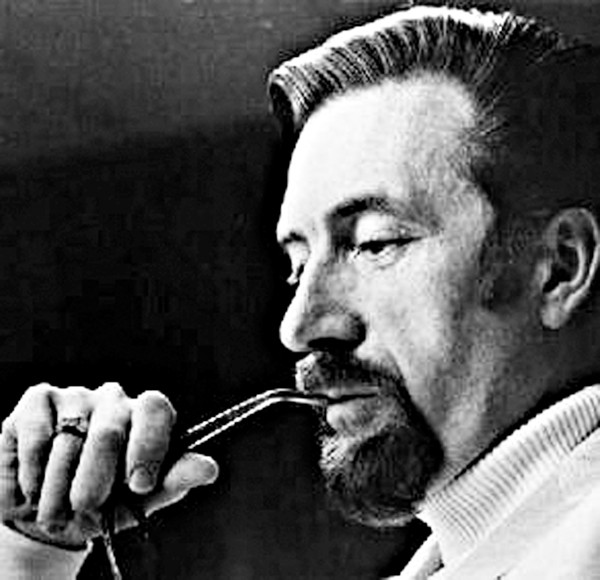

“I’m gonna have a hit if it’s the last thing I do!” exclaims Albert King. “Hanging around the studio for three days in a row now, I think ain’t nobody can get a hit outta here but Sam and Dave, Rufus Thomas, or Carla Thomas … I can play the blues myself! Yeah! Gonna get every disc jockey in business across the country. If he don’t dig this, he got a hole in his soul!” King is speaking over a song from half a century ago, but it sounds as urgent as this morning’s news. Such was the galvanizing spirit animating Stax studios throughout 1968 and 1969.

By then, the need for hits had become a matter of survival: Atlantic Records, which had distributed all Stax material through 1967, was enforcing the contractual fine print that made all Stax master recordings the property of Atlantic. Severing relations with the industry giant, Stax, guided by co-owner Al Bell, began cranking out new music at a furious pace.

Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music

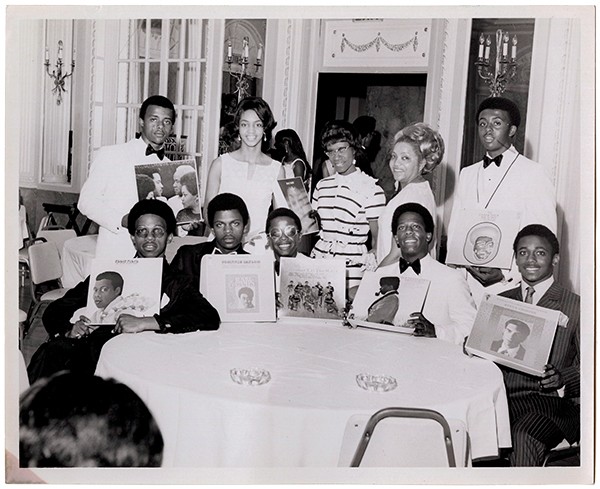

Soul Explosion Summit Atendees with Covers

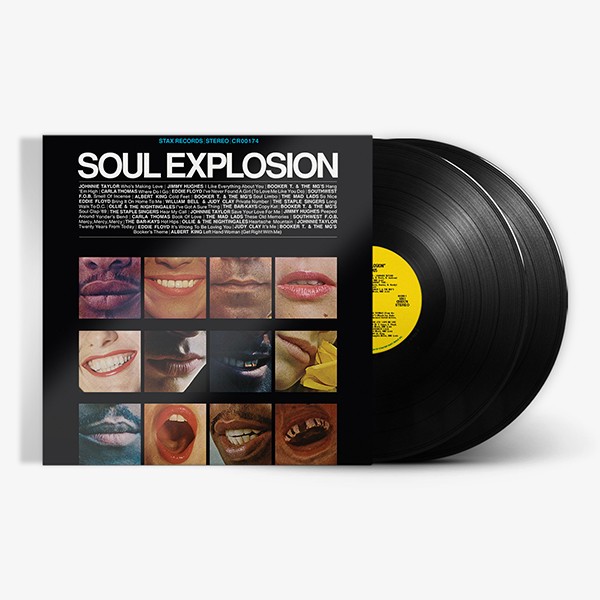

It was known as the “Soul Explosion,” and Craft Recordings has just re-released a two-LP set by that name that served as the capstone of this Herculean effort. Last year, the five-CD Stax ’68: A Memphis Story gathered every release from the first year of the label’s reinvention. The new double-vinyl reissue, identical in appearance to the original 1969 album, captures the time even more viscerally. Deanie Parker, former head of Stax publicity (and, more recently, president and CEO of the Soulsville Museum), recalls the time wistfully. “That was a time when people loved to read, to see pictures, to touch the album covers, singles, and labels, and have the artists autograph them.”

The vinyl reissue literally brings it all back home. As part of the label’s “Made in Memphis” campaign, the lacquers were cut by Memphis-based engineer Jeff Powell and manufactured at Memphis Record Pressing. And for Parker, the reissue transports her back to that time. “You’d hear something new and think, ‘Oh, this is fantastic! Look what these people did in the studio! Did you hear what they came up with last night?!’ Overnight, something dynamic could happen creatively, and it would modify the strategies that you had in mind earlier in the week, in terms of how we were gonna package it,” she recalls.

Package it they did, with an ever-refined sense of strategy. The Soul Explosion album assembled the biggest hits of 1968, with other diverse potential hits from that productive year. Johnnie Taylor’s “Who’s Making Love,” the label’s first big post-Atlantic smash, is followed in quick succession by Booker T. & the MGs’ “Hang ‘Em High,” Eddie Floyd’s “I’ve Never Found a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do),” and other chart-toppers and rarities. The LP was assembled for maximum impact, just before the label hosted a massive summit of industry players in May of 1969. As Parker recalls, “That album was the centerpiece.”

Al Bell recalls, “We were multimedia before multimedia was even a thing! During that one weekend in Memphis, we had large projections on the walls the size of movie theater screens, and we had video interspersed with live performances by all of our top acts. The energy during that weekend was like nothing the music industry had seen before.”

Beyond appearing 50 years after the original release, the timing of the reissue was especially poignant, coming only days after the death of John Gary Williams, the star vocalist of the Mad Lads. The LP’s two numbers from that group, “So Nice” and “These Old Memories.” In more ways than one, “these old memories” will “bring new tears.”

Editor’s note: Memorial services for John Gary Williams will be Saturday, June 8th, at the Brown Missionary Baptist Church, 7200 Swinnea in Southaven, 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.