In March 1966, Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted into the Army to fight in the Vietnam War, citing his Islamic faith as a reason and claiming conscientious objector status. At the peak of his boxing career, he was banned from the sport and spent the next four years in and out of the courtroom. In October 1970, he was finally granted a license to fight in Georgia, and on October 26th, he faced Jerry “The Bellflower Bomber” Quarry in Atlanta. In front of a sellout crowd, Ali took Quarry down in only three rounds, setting off a night of celebration in Atlanta’s Black community. At one infamous party, a group of Black gangsters celebrating the victory were set up and robbed at gunpoint by another group of Black gangsters, setting off a chain reaction of botched reprisals and mutual misunderstandings worthy of a Coen Brothers movie.

Years later, journalist Jeff Keating, writing for the Atlanta alternative weekly Creative Loafing, discovered that the person who threw the party, an ambitious hustler known as Chicken Man, was not killed, as had long been reported, but instead had survived the ordeal and was living under an assumed name in Atlanta. Keating recounted the too-weird-to-be-true story in his true crime podcast Fight Night. Released in 2020 during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, it became a huge hit. Writer/producer Shaye Ogbonna and comedian Kevin Hart pitched the story to Universal Television, who ultimately ordered an eight-part limited series for their new streaming service Peacock.

One of the first calls they made was to Memphis director Craig Brewer. “I got this job the old-fashioned way,” he says. “I got a call from my agents saying that [executive producer] Will Packer and Kevin Hart wanted to meet with me on a project. … Shaye, the creator, has been a fan of my films, particularly Hustle & Flow, which he saw in Atlanta.”

Brewer was intrigued by the story and impressed with the rough drafts of the first two episodes, which were all that existed at the time. “I remember reading the script and thinking to myself, ‘This guy Shaye and I, I think are gonna really get along.’ We have the same interests in movies and TV and music. But more importantly, it’s something I always remember John Singleton talking to me about: ‘Is there regional specificity to this voice?’ And I was like, yeah, this feels like a guy from the South, in Atlanta, making movies from his heart, his culture, and his experience. It felt real to me; it felt furnished and honest and, above all, exciting.”

Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist was on its way to the screen.

Putting the Team Together

Kevin Hart’s Hartbeat and Will Packer Media had produced the podcast, says Brewer. “Kevin was always going to be Chicken Man. That was from the jump. Then I came on and we started putting together the other cast members.”

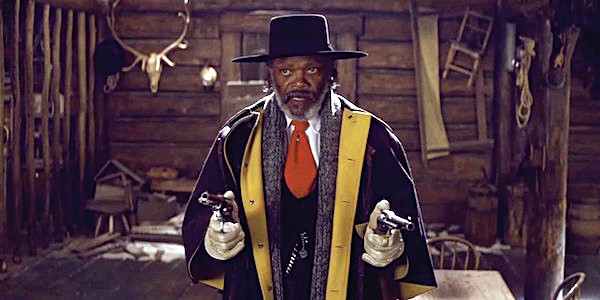

Samuel L. Jackson, an acting legend who Brewer worked with in 2006’s Black Snake Moan, was quickly cast as New York gangster Frank Moten. Taraji P. Henson, who was the breakout star of Hustle & Flow, came onboard as Vivian, Chicken Man’s partner in crime. “She was always at the top of the list,” says Brewer. “Then Will Packer called me and said, ‘We gotta go get your boy Terrence.’”

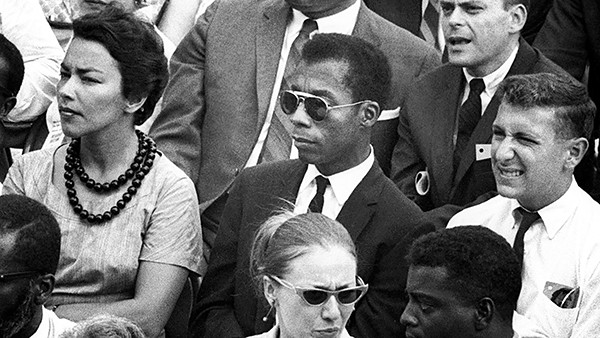

Gangsters “Cadillac” Richie (Howard) and Frank Moten (Jackson) land in Atlanta with their entourage. (Photo: Parrish Lewis/PEACOCK)

The producers thought Terrence Howard, star of Hustle & Flow, would be perfect for gangster Richard “Cadillac” Wheeler. “I’m speaking to you from New Jersey, so I’m speaking to you from Cadillac Richie’s territory,” says Brewer.

Terrence Howard and Marsha Stephanie Blake (Photo: Eli Joshua Adé/PEACOCK)

Taraji P. Henson stars as Vivian Thomas. (Photo: Parrish Lewis/PEACOCK)

After Hustle, Brewer had directed Henson and Howard in the hit TV series Empire. “I called up Terrence, and I was kinda talking him into doing the show. I said to him, ‘Listen, it’s me. I’m gonna let you get up on that tight rope like you usually do. I’ll be your net. What I want you to do is bring your creativity to this and create this character because he’s an important character as the series goes on. I’m gonna just agree to anything you wanna do and help you get it.’ Then he said, ‘Well, I wanna look like one of the Bee Gees. That’s what I wanna do.’ I just remember feeling like, ‘Oh no, what is this gonna look like?’ But then he showed up, and I thought, ‘This cat is gonna steal this show because he looks amazing. … I don’t know if he’s gonna take it off ever again.’”

Detective J.D. Hudson (Cheadle)

protects Muhammad Ali (Dexter

Darden) before the fight.

(Photo: Eli Joshua Adé/PEACOCK)

The final big get for the cast was Don Cheadle. The actor/director was on Brewer’s bucket list. “I have always wanted to work with Don, and it was everything that I could have dreamed for and more. He’s a great actor, yes. But I would say that with him — and I would put Sam Jackson in the same category — you’re not just getting somebody’s acting talent, you’re getting their experience of making, watching, and living the art of storytelling. They have an eye for things that some younger actors do not have. Are we telling the right story? They make you better because they hold you to a standard of making sure that you’re doing right, not only by their character, but how their character interacts with everybody. So there were countless times that Don Cheadle would take me and Shaye off into his trailer, and we would work a scene. By the time we left the trailer, Shaye and I would look at each other and just go, ‘Man, the scene is just so much better!’”

Fight Night is filled with star power, in a way very few TV shows have ever been. “The thing about movie stars is, they are decided by the people,” says Brewer. “This show is packed with five movie stars.”

Hotlanta

Fight Night was filmed in Atlanta, Georgia. The series features extensive location shoots among the split-level ranch houses of the suburbs and in the dense city center. Crucial scenes were shot in the distinctive Hyatt Regency Atlanta, whose 22-story atrium influenced hotel design for a generation.

“There is a crucial monologue in episode two that Sam Jackson delivers, where he’s talking about his vision for Atlanta,” says Brewer. “He wants Black people put in places of power, and for the economic future of Atlanta to be Black. It’s funny because you look at the monologue, and you can imagine if it were being said in 1970 to an all-white audience, it may seem outlandish. But last night at the premiere, there were cheers because you realize that dream is here and realized. So it’s very interesting to talk to young people about Atlanta at this crucial time in its history, in the early 1970s, where they were on a campaign that I feel is comparable to Memphis’ history, and to Memphis’ present, which is to deny that you are living, working, and thriving in a Black city. It is to your own peril if you fight against it.

“Atlanta is a city that is open for business. We’re too busy to be dealing with any of that racist bullshit. We’re here to make some money, and I’ll be damned if that’s not the Atlanta that I go to all the time when I’m filming these movies. This is my third project in Atlanta. I’ve been there the whole time that Atlanta has said that they wanna be the next Hollywood. And so many people saying, well, that’s not gonna last, or this is gonna be transitional, or the industry is gonna change. I am telling you right now, no one wants to call it out, but production in Atlanta is there to stay. I don’t see this returning back to Hollywood as long as there’s places like Atlanta.”

Brewer had worked on episodic network TV with Empire, but Fight Night was his first limited series, a form that has become more common in the streaming era. Brewer compares the experience to shooting an eight-hour movie. Brewer directed the first two and last two episodes, and collaborated on the writing of the entire series. He describes the process as a mixture of careful prep and on-the-fly improv.

“I got a call from Shaye saying, ‘We got this idea to do the scene between Sam Jackson and Don Cheadle in an interrogation room,’” Brewer recalls. “We locked ourselves in a room and banged out this scene, probably had it written by like 8 o’clock, 9 o’clock at night. Then, the following morning, I went down to the sound stage and there they were, doing the scene that mere hours ago we had worked on. It’s amazing how fast it all happened. It was just so special because there’d be these moments where Shaye and I would write something, and we knew, ‘Okay, right here, Sam’s gonna probably make this part better. So let’s move on and know that he’s gonna come up with something great to say here — and sure enough, he did! It was this great moment of watching these titans just being amazing.”

Kevin Hart, one of the driving forces behind the development of the series, took the most chances. One of the best-known comedians in the country found a new lane as a dramatic actor. “I had a moment where I saw something that I had never seen before, and it kind of knocked me on my ass,” says Brewer. “It’s in episode two where Kevin Hart’s character is in grave danger, and he has to make a plea for his life. I’m sitting there at my monitor, and I watch Kevin make this tearful plea. That was one of the most real things I’ve ever seen an actor do. I remember just sitting there in awe thinking, ‘How could someone as successful as Kevin Hart actually have a whole other store of talent inside of him that we’ve yet to see? How can it be that he could drop everything that he is as the funniest man on the planet and actually be a dramatic actor?’ You make an assumption about a person, that maybe they don’t have this particular arrow in their quiver, and then suddenly they hit a bull’s-eye. I was stunned. Everyone was stunned. Terrence came up to me and he goes, ‘That cat’s the real deal.’”

Making the Music

Fight Night is set in 1970, a high point in the history of soul, funk, and R&B music. For Scott Bomar, producer and musician behind such acts as The Bo-Keys, that’s his wheelhouse. Bomar and Brewer have worked together on five movie and TV projects, beginning with Hustle & Flow in 2005. “I feel like I got spoiled working with him early on because he’s so musical,” Bomar says. “I find that the way Craig shoots, the way he directs his actors, the way he edits, it’s got a rhythm to it. I’ve worked with him enough now to kind of know what his rhythm is.”

Bomar says he was in “summer home repair mode” when Brewer called him out of the blue. “He said, I’m working on this TV show. Theoretically, if you had this gig, would you be able to do it? Are you available? And I’m like, sure, yeah. I can do it. I knew it was a pretty quick turnaround, but I had no idea exactly how quick of a turnaround it was. I think there were people involved who had their doubts on whether or not it was possible to do what we did in the amount of time we did it.”

Bomar and Brewer recorded the score to Fight Night at Sam Phillips Recording in Memphis. They had one week to take each episode from concept to final mix. “I can’t say enough about my collaboration with Scott Bomar,” says Brewer. “It’s something that truly is a collaboration. I see the scene, and Scott and I start just kind of grooving to a beat, to a track that has yet to be written. We start with rhythm. It really is kind of a Memphis way of doing it.”

Bomar enlisted several of his stable of veteran Memphis players, including drummer Willie Hall, who played on Isaac Hayes’ “Theme From Shaft.” Joe Restivo played guitar; Mark Franklin, Kirk Smothers, and Art Edmaiston contributed horn parts, along with Kameron Whalum, Gary Topper, and Yella P. Behind the board were veteran producer Kevin Houston and Jake Ferguson, who recently returned to Memphis after collaborating with superstar producer Mark Ronson. Most recently, Ferguson worked on the soundtrack to Barbie. “I feel like Craig came in and basically taught a master class on TV scoring,” Ferguson says.

“It’s quite a bit different than film because the schedule’s so accelerated,” says Bomar.

A 1970s vintage mini Moog synthesizer Bomar found in a closet at Sam Phillips Recording played a major role in creating the series’ soundscapes. In some cases, Bomar says they didn’t have time to assemble a full band, so he would have to play almost all of the instruments himself. “I’d say that this is the closest thing to a solo record I’ve ever made,” he laughs.

“It was fascinating to hear Scott and Craig talk about Atlanta in the ’70s and all the inspirations they had,” says Ferguson. “Musically, it was so cool to see how we can take, quote, unquote, ‘modern instruments’ and make them feel like you’re back in the ’70s. When we finished the first two episodes, it was just incredible to see how much the scenes would come to life with the music we added.”

“When we had the first mix, one of the producers said, ‘We asked Scott to do the impossible, and he’s done it,’” says Bomar. “That’s one of the best compliments I’ve ever gotten.”

Final Fight

The first three episodes of Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist premiered on Peacock Thursday, September 5th. New episodes will drop every Thursday for the next five weeks. The night before it hit streaming, there was a star-studded premiere at Lincoln Center in New York City. I interviewed Brewer the next morning, as he was beginning preparations for his next project, a film he wrote called Song Sung Blue starring Hugh Jackman. The director was still reeling from the reception to Fight Night. “When you’re dealing with a brand like Will Packer and Kevin Hart, that means it’s gonna be a party. You can’t just do wine and cheese and a floral arrangement. There were dancers dressed in some of the outfits from the show. There was a Cadillac in the middle of the dance floor. It’s just a party and everybody was there! My son [Graham], I had to pull his ass off the dance floor last night at like 1 a.m., saying, ‘I gotta work, son! Let’s go!’ But he was out there, doing the wobble with everybody else. … It was such a great thing to see it with a crowd. Yeah, I think we got a great show here.”