So the government fired five shots at John Ford and hit him once, federal prosecutors kept their Tennessee Waltz winning streak unbroken, and the E-Cycle FBI Actors Repertory Company closed another Memphis performance.

This one was a little shaky. Prosecutors said they are sending out a strong message of deterrence. But four years after its inception, Operation Tennessee Waltz still looks more like a sting targeting Democrats in Memphis and Chattanooga than a purge of “systemic corruption” in state government. Its success is due to secret tapes of a handful of public officials taking bribes from a fake company that their colleagues were too honest, too smart, or too irrelevant to deal with.

Or maybe they just know how to Google.

Type “Joe Carson” and “FBI undercover” in a Google search and you find that Joe Carroll, whose FBI undercover name is Joe Carson, starred in at least two FBI undercover productions before Tennessee Waltz. In “Operation Lightning Strike” from 1991 to 1994, he posed as a big shot for Eastern Tech Manufacturing Company, a phony business seeking crooked contracts in the aerospace industry in Houston. His undercover name? Joe Carson. The sting resulted in indictments and a mistrial.

In 2001, Carroll and the FBI resurrected “Joe Carson” in a Maryland undercover operation targeting state lawmakers. His phony Atlanta-based company was seeking crooked deals with Comcast for fiber-optic contracts. A former state senator, Thomas Bromwell, is under federal indictment but has not yet gone on trial.

Give the FBI, Carson, L.C. McNeil, and Tim Willis credit for pulling off a two-year Tennessee undercover operation, including the 2004 and 2005 legislative sessions, without a leak. The Ford tapes were so powerful that the defense barely tried to explain them away. They left no doubt that money was exchanged for special legislation. The sting worked, but it hasn’t yet exposed corruption in real deals in high places.

Operation Tennessee Waltz started in 2003, after FBI agents investigating phony contracts in Shelby County Juvenile Court found evidence of “systemic corruption” in state government. Seven of the 11 Tennessee Waltz indictments were announced at a press conference in Memphis on May 26, 2005. The investigation, convictions, and guilty pleas since 2003 have produced no indictments for bribery or other wrongdoing by any full-time state employee, lobbyist, or contractor. On tape, Ford boasts that he is the man who “does the deals” and “control[s] the votes,” but his trial was all about E-Cycle and legislation that never got beyond committee.

“Systemic corruption,” it seems, is a product of Shelby County and Hamilton County, two of the 95 counties in Tennessee. Five Memphians have been convicted or pleaded guilty. In a conversation with agent McNeil in 2004, Barry Myers, the bag man who later became a government witness, explained why lawmakers were wary of the free-spending black millionaire: “To be honest with ya’, most of the money I used to pick up come from white folks, white males, established businessmen that would send money to Kathryn, Lois, Roscoe, and John. That’s where the real money came from.”

Who spent the “real money” for “the big juice” — Ford, Roscoe Dixon, Kathryn Bowers, and Lois DeBerry? We don’t know. The payment of “consulting fees” by real companies is at the heart of Ford’s pending case in Nashville, which is not part of Tennessee Waltz. He has a hearing on May 3rd. Eli Richardson, assistant U.S. attorney in Nashville, said “it remains to be seen” how the Memphis case will mesh with the Nashville case, which apparently relies on old-fashioned evidence and witnesses.

“The conviction in Memphis opens up all kinds of possibilities for plea negotiation that didn’t exist before,” said Bud Cummins, a former federal prosecutor in Arkansas. “But there is not a whole lot of pressure on the government. They are still holding most of the cards. My best guess is they’re pretty intent on going to trial.”

Ford could appeal his Memphis conviction and request a sentencing delay until after he is tried in Nashville. If he is sentenced and goes to prison before his appeal is resolved, he could still be tried on the Nashville charges.

“We try people all the time who are sitting there in prison clothes,” Cummins said, although Ford would probably be unrestrained and in civilian clothes in the courtroom, with a federal marshal standing behind him.

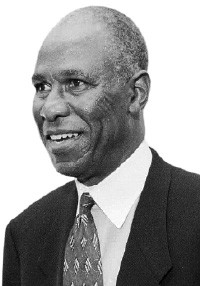

(AP Photo/Wade Payne)

(AP Photo/Wade Payne)  (AP Photo/John L. Focht)

(AP Photo/John L. Focht)

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker