In last week’s “Politics” column, I tried to sketch out the itinerary that brought us from a sense of distracted unconcern about Shelby County’s two co-existing public school systems into the high dudgeon that has characterized the ongoing confrontation between the two systems, Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools.

Ironically, the next milestone along that pathway, a citywide referendum next Tuesday, March 8th, on the transfer of administrative authority from MCS to SCS, is apparently going to happen with little incident and less attention — almost as if it were not an epochal event but just another special election in a seemingly interminable recent series that has drawn fewer and fewer voters out to the polls.

Speaking of special elections, there happens to be one on the ballot in some of the city’s northern precincts — an utterly pro forma vote to confirm the election of state representative Antonio “2 Shay” Parkinson, who won last month’s Democratic primary for the late Ulysses Jones’ vacant seat in state House District 98, faced no opposition in Tuesday’s general election, and, as a consequence, has already been appointed by the county commission.

Even had that election been closely contested, it could not have seriously affected the balance of power in Nashville, where last November’s Republican landslide left the GOP in control of the state Senate by a margin of 20 to 13 and the House by 64-34, counting Parkinson, and 65-34, if you also count former Speaker Kent Williams of Elizabethton, a de facto independent forced to call himself a “Carter County Republican” after his expulsion from the state GOP for accepting Democratic votes for speaker in 2009.

Even so, with only 12,948 voters in the city having availed themselves of early voting as the week began — out of a total citywide registration of some 400,000-plus — Parkinson’s solo victory lap, however statistically meaningless, could not have trailed by much the turnout rate for the all-important referendum on the charter transfer.

“All-important” is not an exaggerated description. Consider merely what happens if the number of “no” votes should end up larger than the ones for “yes.”

Norris-Todd

Take the so-called Norris-Todd Bill, for example. Fast-tracked in both chambers of the Tennessee General Assembly by the Republican legislative leadership and rubber-stamped by the obedient GOP cadres in both Senate and House, the bill was brought by two Collierville Republicans, Senate majority leader Mark Norris, its probable designer, and state representative Curry Todd, neither of whom would admit of a solitary amendment suggested by their chambers’ out-numbered Democrats. And newly inaugurated Governor Bill Haslam wasted little time in signing the bill into law.

The bill’s provisions, clearly and ingeniously designed to quell suburban anxieties and to blunt or even nullify the effect of a “yes” vote on the referendum, would only go into effect in the case it passes. Thereafter, the alchemy begins.

If the referendum succeeds, stage two would be the appointment of a 21-member “planning commission” heavily oriented toward suburban sensibilities. The Shelby County mayor, the Shelby County Schools board chairman, the governor, and the speakers of the House and Senate, all Republicans, would, by membership and/or right of appointment, account for 16 of the 21 members. The other five members would be named by the MCS board chair, who at the moment is Freda Williams, a declared opponent (like the clearly self-interested city school superintendent Kriner Cash himself) of the MCS-SCS merger.

To the consternation of Memphis mayor A C Wharton, neither he nor any other representative of city government was extended the right to make appointments by those whom the mayor bitterly described as “the gods of Nashville.”

Whatever sort of planning the newly created commission would end up doing, it would be required by the terms of the new law to consume fully two and a half years in doing it. Not until August 2013 could a merger of the two school systems take place. By that time, the various entities of suburban Shelby County would have had ample time — surprise! — to structure whatever combination of new municipal or special school districts would allow them to keep their distance, as before, from the schools and administration of what had been MCS.

The final provision of Norris-Todd — its punch line, if you will — is that the new law, which starts out by co-opting the March 8th referendum, would, as of the aforesaid August 2013 merger, strike down existing state prohibitions — for the suburbs of Shelby County only — against the walled-off separate districts which the merger was designed to prevent.

That’s one irony. Here’s another: Those erstwhile city schools would now — as the dominant and perhaps only component of Shelby County Schools — be the de facto county schools. And the former county schools would, if grouped into municipal districts, become city schools.

Yet if the referendum should fail, none of this would happen. Or not that way. Without a successful referendum to trigger it, Norris-Todd would have no provenance. But the two parallel systems, MCS and SCS, would almost certainly not revert to the status quo ante.

What would likely happen instead is that the legislature would go ahead and enact — now, rather than later — legislation enabling new special and/or municipal school districts, perhaps for all of Tennessee. That is the stated goal of the Tennessee Association of School Boards, which is even now getting what it wants from the assembly in new bills to create multiple new restrictions on unions and other organizations which purport to speak for the state’s teachers.

City Council and County Commission

A “no” vote on March 8th would also likely nullify actions already taken by the Memphis City Council and the Shelby County Commission. The council, it will be recalled, voted in two stages (January 18th and February 10th) to accept the surrender of the Memphis City Schools charter. This was a parallel track enabled by the ambiguous nature of the MCS board’s resolution of December 20th, which — by referring to two different Tennessee statutes — both authorized an outright surrender of its charter and called for a referendum to transfer its authority to Shelby County Schools.

The council, motivated as much by a desire to defend the city’s right to self-determination as by support of school unification per se, explicitly regarded its actions as necessary backups to the referendum process, and various council members have made it clear that, should the March 8th referendum fail, they would be prepared to revote, revoking their support of a charter surrender in accordance with what would then seem to be the people’s will. Whether a majority of council members would do so remains to be seen, however.

Meanwhile, the county commission, something of a political anomaly in the current political environment in that it is preponderantly both Democratic and urban-oriented, has acted decisively to stake its own claim to guide the transition into a unified all-county school system. Current commission chairman Sidney Chism, an inner-city Democrat, wasted little time in warning off Wharton and Shelby County mayor Mark Luttrell when the two mayors, back at an early January press conference, seemed to be attempting to set themselves up as arbiters of a transition process. “This process will start with and end with the Shelby County Commission,” Chism insisted.

Allied with other commission Democrats, and with urban Republicans Mike Carpenter and Mike Ritz, the chairman went on to oversee a series of ad hoc committee meetings that culminated with several votes at this week’s regular public commission meeting.

On Monday, the commission majority established a provisional interim all-county school board, comprised of 25 districts; set up a machinery for interviewing possible appointees to the seats; and called for all-county elections to the new board (possibly scaled down in number by then) in August 2012. That date, it will be noted, precedes by a year the Norris-Todd bill’s start date for a merger.

It goes without saying that all of this elaborate preparation becomes purely academic if the March 8th referendum, on which it is predicated, should end in a “no” vote.

Legal Contests

In the event of a “yes” vote, however (and, light turnout or otherwise, such polls as have been taken suggest that outcome), litigation of various overlapping kinds is inevitable — enough so that, as MCS attorney Dorsey Hopson advised his board recently, Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools might continue to exist as separate entities for as long as eight years.

Norris-Todd is sure to be contested on several grounds, including the fact that, arguably, it constitutes an ex post facto action against a process already under way under legitimate prior law. The actions of the MCS board and the Memphis City Council are already targeted by a federal suit filed by Shelby County Schools, SCS chairman David Pickler having contended that those actions are “not lawful” and should be declared “null and void.” (Pickler also declined to recognize Wharton as an executor of sorts for MCS, as the mayor had been designated by the city council.)

And the Shelby County Commission’s best-laid schemes could, in the vintage words of poet Robert Burns, also go agley. A hard-core contingent of resisting suburban commissioners has predicted just that, on the grounds that Norris-Todd, if upheld by the courts, would take precedence as state law.

Where do we go from here? Not only is the destination uncertain, so is the timetable. All that is certain is that next week’s vote will point in a given and, one way or another, brand-new direction. — Jackson Baker

School Choice

School merger “yeas” and “nays” recall where they came from.

In many ways, they are much more alike than different.

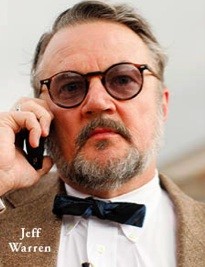

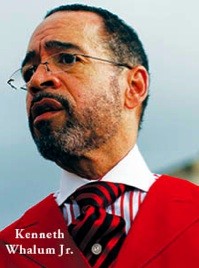

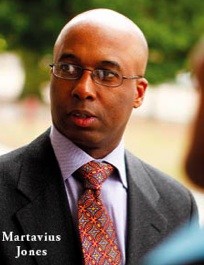

Kenneth Whalum, Jeff Warren, Martavius Jones, and Tomeka Hart are Memphis school board members with professional occupations, college degrees, and an unquestionable commitment to public service and a job that pays $5,000 a year and all the headaches you want.

And they are all personally invested in Memphis City Schools. Whalum graduated from Melrose High School, Jones from Central High School, and Hart from Trezevant High School. Whalum, a minister with a law degree, and Warren, a physician, sent their children to city schools although they could afford private school tuition. Whalum’s three sons graduated from Overton High School. Two of Warren’s sons graduated from Central High School, and a third will start there in the fall.

But on the issue of merging the city and county school systems and surrendering the MCS charter, Whalum and Warren are staunchly opposed, while Jones and Hart are the main proponents as well as the instigators of the March 8th referendum. One year ago, all of them, with the possible exception of Whalum, were little known in the broader community of Memphis and Shelby County. Now they are, if not household names, at least familiar faces on the local news.

School board members are leading the fight on both sides of the debate partly by default. Memphis mayor A C Wharton only recently announced his support for a merger, and Shelby County mayor Mark Luttrell has stayed quiet. Business leaders have shown little active interest in the schools issue compared to the organized if ineffective government consolidation campaign in 2010 or the pull-out-all-stops celebration a month ago for the Mitsubishi Electric announcement.

The schools issue gets a lot of lip service for being historic and important, but the rallies and debates have generally drawn small crowds. The biggest one so far was in Germantown, where more than 600 people showed up to talk about forming an independent school system.

Although they can’t vote in the referendum, county residents outside of Memphis are fired up, because they feel threatened and their children attend public school. Proponents have a fundamental problem: This stuff is complicated. At a meeting in Frayser, U of M law professor Daniel Kiel and Rhodes College political scientist Marcus Pohlmann spent nearly an hour explaining charter surrender, legislative process, private bills, property taxes, school funding, and consolidation history to a group of about 40 people, including several high school students and working parents. It was, to be polite, a struggle.

Elected boards reflect the diversity of our school systems. Several members of the Memphis City Council are graduates of Memphis high schools. Wanda Halbert is a public school parent. Shea Flinn is a private-school parent and graduate. Jim Strickland’s children attend Catholic schools. Bill Morrison and Ed Ford Jr. are MCS teachers but have recused themselves from debates and votes on charter surrender. Shelby County school board chairman David Pickler’s children attended county public schools. Board member Ernest Chism is a former principal of Germantown High School, and his colleague Joe Clayton was principal of Overton High School in MCS, before moving to Briarcrest Christian High School in 1974 as principal for the next 22 years.

At the center of the debate are Warren, Whalum, Jones, and Hart. Who are they? Interviews with them show how the school choices they made in their own lives shaped their positions on the charter debate.

Jeff Warren’s three sons, ages 21, 19, and 13, all went to the optional program at Snowden Elementary School in Midtown. While many of their classmates went on to White Station High School, the Warrens went to Central, where less than 10 percent of the students are white. The oldest son will graduate from Yale University this year and plans to work for Teach For America.

Warren, a primary-care physician, went to public schools in Saulsberry, North Carolina, at a time when all-black schools were closing and merging with white schools. He also went to college at Yale. His wife, K.C. Warren, attended White Station High School in Memphis until transferring to Lausanne Collegiate School during the busing years of the 1970s.

Warren tried unsuccessfully to reach a compromise with Shelby County school system representatives before the MCS board voted 5-4 to surrender the charter. He voted no. A liberal himself, Warren says “the liberals think we are going to right the wrongs of the ’70s.”

Warren believes merging the systems will cause another round of middle-class flight from public education and cost MCS as much as $1 billion in funding over the next 12 years.

“Shelby County has not given us any increase in school funding since I have been on the school board. In three years, Shelby County Schools is legally authorized to form a special school district under state law.”

Kenneth Whalum Jr. and Warren have had their scraps on the school board, but they have joined forces to oppose the referendum. Whalum also has three sons who are MCS products. All of them graduated from the performing arts program at Overton High School and now live in New York City. One is a vocalist, one a saxophonist, and one plays the trombone. Their uncle is professional jazz musician Kirk Whalum.

Kenneth Whalum attended Sherwood Junior High School, Messick High School, and Melrose High School during the busing years. His wife graduated from Carver High School. Whalum has fond memories of Messick and Melrose, but not Sherwood.

“I remember being called a nigger,” he says.

He will tell anyone who will listen that charter surrender is not the same as school consolidation and that MCS will suffer. He thinks Overton’s optional arts program could be a model for MCS, but the school is down to just 460 students and is 98 percent black.

“I am trying to get back to that level of excellence, but we can’t do it if we’re all over the place in terms of curriculum, and we certainly won’t get it if we surrender the charter. Creative and performing arts is an optional program, and they don’t do that in Shelby County.”

Martavius Jones, a financial adviser, has taken on the job of making the case for charter surrender in order to preserve the long-term fiscal solvency of MCS.

Jones attended Bellevue Junior High School and graduated from Central High School in 1986.

His parents both went to Melrose. As a boy, Jones started school at Sherwood Elementary because of busing, but he was too young to remember much of any great significance.

“It was just part of going to school,” he says.

He later chose to enter the optional program at Central High School instead of going to Oakhaven, which was his neighborhood school. The academic program at Central was better, he says. Jones was one of 11 members of his graduating class who went on to Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Shelby County does not have optional schools.

“I would not have a problem with optional schools going away if and when we have quality schools throughout the county,” he says.

Tomeka Hart, an attorney and CEO of the Memphis Urban League, is Jones’ frequent speaking companion on the pro side of charter debates. She attended Snowden elementary and middle school and graduated from Trezevant High School in Frayser in 1989, when there were still several white students. The school is now 99 percent black.

Her parents, both of whom grew up in the days of Jim Crow segregation in Memphis, put her in the optional program at Snowden instead of their neighborhood school, Georgian Hills. With her grades and motivation, Hart would have been a candidate for an academic optional high school, but she went to Trezevant instead.

“Trezevant fared me well, but I only took one advanced placement course, because that was all that was offered. When I got to UT-Knoxville, many of my classmates had taken multiple AP courses. That was one of the first times that I began to understand inequities. Optional schools leave some students out.

“I would have been okay anywhere, but lots of students are stuck in the system and did not have the same opportunities. Your mom shouldn’t have to get a letter saying your achievement scores are high enough to get you into a ‘good’ school.” — John Branston