The short answer is “no” but there sure are some interesting parallels.

In 1973 and 1974, some 30,000 students left the Memphis public school system in white flight in reaction to court-ordered busing for integration. In 2013, some 30,000 students could leave the “unified” Shelby County schools to attend new municipal school systems, if the voters approve and the courts allow the establishment of such systems.

White flight cut the enrollment of MCS from 148,000 students to about 120,000 students. Five or six municipal school systems would cut the enrollment of the unified system from about 148,000 students to about 120,000 students.

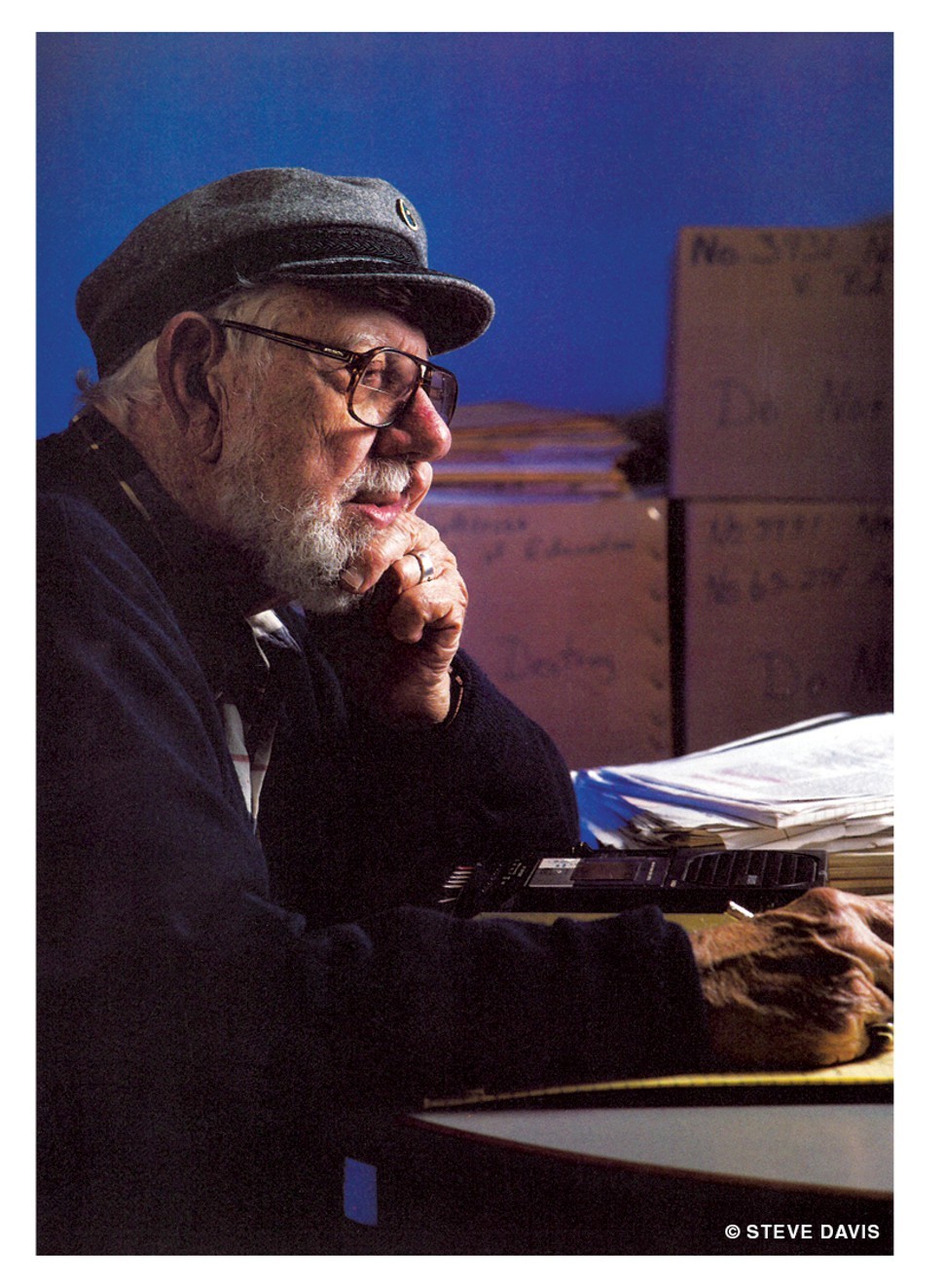

A federal judge in Memphis is once again at the center of the story that is getting national as well as local attention. In 1973 it was Robert McRae — a Central High School graduate and Lyndon Johnson appointee who wore a red judicial robe and was capable of flashes of temper and impatience from the bench. In retirement, he joked that he was Central’s most famous graduate since Machine Gun Kelly. Now the judge of the hour is Samuel H. Mays, a White Station High School graduate and George H. W. Bush appointee whose low-key courtroom mannerisms are often as folksy and wry as they are wise.

Mays wrote last year’s order and consent decree on the schools merger and now faces a Shelby County Commission challenge to the scheduled August 2nd referendum on municipal schools. His ruling on “ripeness” last year invited such a challenge at a later date, and that time has come.

Mays, I believe, is the perfect person for the job. He graduated from White Station in 1966, smack in the middle of the one-grade-a-year desegregation plan that was scrapped in favor of busing. He is a graduate of Yale Law School in 1973, and had to have been aware of what was happening in his hometown and his high school alma mater. Most important, he has experience in the rough-and-tumble world of state politics as chief of staff for former Tennessee Gov. Don Sundquist.

McRae kept a box of hate mail that he drew upon when completing his nine-part oral history for the Mississippi Valley Collection at the University of Memphis. I don’t know this for a fact, but I doubt that Mays gets much if any hate mail; he is rarely criticized in the thousands of online comments on schools stories I have seen.

I spent several hours interviewing McRae in his retirement. He was not a man to shirk a task, but he was a somewhat reluctant history maker and fully aware of the consequences of busing.

“I tried to stop with Plan A but the appeals court wouldn’t allow that,” he said in 1995. “I was disappointed in the reaction to Plan Z. But I had to keep a stiff upper lip because this [reaction] was an act of defiance. Still I was disappointed that we hadn’t come up with something that worked.

“No, I wouldn’t do it any other way. I am convinced there was nobody who could have settled this the way the parties were opposed. Somewhere along the line I became convinced that it was morally right to desegregate the schools.”

Plan Z, of course, was the “terminal” school desegregation plan, so named because McRae (who ate his own cooking by sending his children to Memphis public schools) didn’t want a succession of plans “A” through “Y.” But it was forever associated with one of its authors, MCS employee O.Z Stephens, who told me years later that “my identification with Plan Z killed me professionally in the school system.” His son David works for Shelby County Schools and has attended all of the meetings of the transition team and school board.

The senior Stephens thought busing was a disaster and has predicted that MCS charter surrender could also have dire consequences, but he is anything but a suburban firebrand or hater. He gave his working life to MCS and greatly respected both McRae and Willie Herenton, the superintendent during much of his tenure. McRae, he said, was “as easy on the school system and the city as he could possibly have been” and a less courageous judge could have passed the whole mess on to the appeals court.

For these and other reasons I am still somewhat hopeful about the schools merger. Pure conjecture on my part, but I suspect Mays is exercising as much judicial restraint as possible and well knows the limitations of a court-ordered “solution” to school desegregation and school system unification. He will let the political process play out as long as he can.

My attention span is not long, and I would rather walk on hot coals than sit through a five-hour meeting. But there is something positive and substantial in the Transition Planning Commission and, especially, the unified 23-member school board, even though it is not long for this world. Old white folks from the ‘burbs sit next to young black folks from Memphis, old black folks from the city sit next to young white folks from the suburbs; they look and listen, and speak their minds publicly. It’s hard to hate someone you’re sitting next to that long. John Aitken sits next to Kriner Cash and they occasionally share a private joke. Martavius Jones and David Pickler have probably spent more time together over the last two years than some spouses.

For this to transcend symbolism, both sides will have to compromise. The procedural shenanigans must end. We’re on the clock. MCS gave up its charter. Actions have consequences. I’m an Aitken fan, but that may be too much to ask, as even he knows, and he says he would willingly serve as an assistant superintendent. If Cash gets the job and really wants it, then I’m a Cash fan because I live in Memphis and want the city to prosper and personal differences don’t mean crap and I don’t believe in miracle-worker superintendents or 11th-hour national searches and Cash has the benefit of experience and knows the lay of the land.

Segregation is not the right word for what the muni’s are seeking. Legal segregation was the law in Robert McRae’s youth. Integration was the driving national force in Hardy Mays’ youth. Resegregation or de-facto segregation (and voluntary integration) is the driving force in Memphis (and many other big cities) in our time. But the suburban schools are not segregated in either a numerical way or a legal way, as the county commission’s filing this week states. There are certainly all-black schools. Southwind High School, which is almost all black, is the one I keep coming back to in my columns because it was such a calculated move when it was approved by the city and county school boards as a joint project. Federal Judge Bernice Donald almost forced the issue five years ago but she was overruled on appeal.

The next thunderbolt from federal court will have to account for the underlying factors that gave us a Southwind High School as well as, potentially, municipal schools. I think it has to come sooner rather than later. Ripe.