Now that Beale Street has been renovated, and neon warms its coldest nights, it’s hard to conjure up the feeling that must have greeted 37-year-old Calvin Newborn when he returned there after making his name in the jazz world.

“I came back to Memphis in 1970,” he told author Robert Gordon. “Beale Street was being torn down. I couldn’t find no place to play. … [I was] playing with Hank Crawford every six months in California. And when I came back to Memphis, I would stay inebriated. It broke my heart, you know, to come on Beale Street and it wasn’t there. So I just went to the liquor store. When they finally tore it completely down, I thought that was the end of Beale Street, you know. But they started to rebuilding, you know, slowly.”

Christian Patterson

Christian Patterson

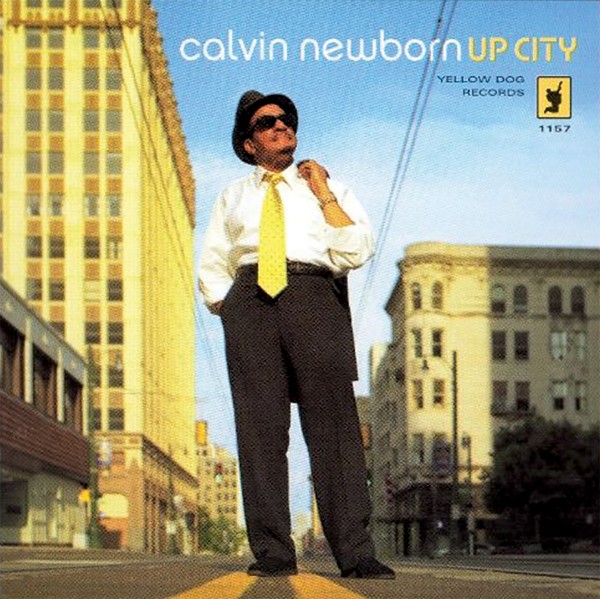

Calvin Newborn

Newborn had dealt with heartbreak before, over the years, in many forms. Happily, he did eventually resume his rightful place as one of Beale’s star attractions. Now the heartbreak’s all ours, since he passed away on December 1st in his adopted home of Jacksonville, Florida. And for lovers of music history, his death marks the loss of more than one man and musician, great enough in his own right. Calvin was the last of the epoch-defining Phineas Newborn Family Showband.

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Herman Green

Family Ties

“When I hear stories about Elvis going and hearing [Calvin’s] dad’s band in the Flamingo Room, and borrowing Calvin’s guitar and sitting in with their family band, I think that Elvis probably got a lot of his feel from their family band. I can see how that was an influence on Elvis,” reflects musician and producer Scott Bomar, who worked with Calvin. “It was quite a band. I think Calvin and his family are that missing link between Sun Records and Stax. They were playing on Sun sessions, and you look at all the people that came through that band. William Bell, George Coleman, Honeymoon Garner, Fred Ford, Charles Lloyd, Booker Little. That whole Newborn Family Band was a cornerstone of Memphis music. It’s a chapter that I don’t think has gotten its due.”

Saxophone legend Charles Lloyd recently tried to give the Newborns their credit, when asked to recall his formative years in Memphis. “I was also blessed that Phineas Newborn discovered me early and took me to the great Irvin Reason for alto lessons. Phineas put me in his father — Phineas Senior’s — band. Together with Junior and his brother, Calvin, we played at the Plantation Inn which was in West Memphis. Phineas became an important mentor and planted the piano seed in me. To this day he still informs me.”

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Calvin with brass note on Beale honoring the Newborn family.

Of course, Phineas Newborn Jr., or just “Junior,” was Calvin’s older sibling, who some would later call “the greatest living jazz pianist.” Their parents, Phineas Sr., or “Finas,” and Mama Rose Newborn, raised them to love and play music, always hoping to carry on as a family band (with Finas on drums). And, for a time, they did. But, ultimately, Junior was too much of a genius on the ivories to be contained by such ambitions. Indeed, Calvin grew up in the shadow of Junior’s gift, something he apparently did not mind one bit. Though the brothers won their first talent show early on as a piano duo, that moment also brought home Junior’s genius to Calvin, who soon after began guitar lessons on an instrument that B.B. King helped him pick out.

Beale Street held a fascination for the whole family, who would initially make the long trek on foot from Orange Mound just to be there, until they moved closer. Finas turned down opportunities to tour with Lionel Hampton and Jimmie Lunceford just to be near his family and the promise of playing music with them. At that time, a flair for music was often a strong familial force. Dr. Herman Green, master of the saxophone and flute, went to Booker T. Washington High School with Calvin. “We grew up together. We been knowing each other since we were babies,” Green says. “The Newborn family, and the Green family, and then the Steinberg family. We had a lot of families together at that time that were musicians, you know? So we came up together, ’cause we had to go to the same school.”

Steve Roberts

Steve Roberts

Calvin Newborn, Chuck Sullivan, Richard Cushing, Robert Barnett (back). Dr. Herman Green & Willie Waldman (front) in FreeWorld. ca. 1990.

Though both brothers were soon proficient enough to tour with established acts (as when Calvin hit the road with Roy Milton’s band), by 1948, their father landed the family group a residency at the Plantation Inn in West Memphis. Green, too, joined the band, as did a young trombonist named Wanda Jones. For a time, Finas’ dream flourished. “Oh, we all was good, man!” recalls Green. “We was playing with his daddy. We had some good singers, like Ma Rainey.” Before long, they moved to the Flamingo Room in Downtown Memphis, and then collectively hit the road with Jackie Brenson, who was touring behind his hit record, “Rocket 88,” recorded (with Ike Turner’s band) by Sam Phillips.

If the family band was tight, Calvin and Wanda were getting even tighter. As Green remembers it, “Wanda, yeah — I’m the one that put ’em together. She was the vocalist with Willie Mitchell. I heard her, and I told Finas Sr. about her. And then we ended up using her for quite a while there. Now, Calvin was my right-hand buddy, man. Junior was in and out of there, you know, but me and Calvin were very close. He told me he was getting ready to get married to Wanda. I said, ‘Well, congratulations.’ He said, ‘Well, you ain’t heard the rest.’ I said, ‘Well, what is it?’ He said, ‘I want you to be my best man.’ And then we lived together in my daddy’s house, when he got married.”

The Phineas Newborn Family Showband was the toast of Memphis, with a plethora of future jazz and soul greats rotating through. And Calvin was distinguishing himself with a talent that his gifted brother did not have: showmanship. As Calvin told author Stanley Booth, “You’d have guitar players to come in and battle me, like Pee Wee Crayton and Gatemouth Brown, and I was battlin’ out there, tearin’ they behind up, ’cause I was dancin’, playin’, puttin’ on a show, slide’ across the flo’.” And flying, as captured in an iconic photo of Calvin in mid-air, his eyes fixed with fierce determination on his fretboard, his legs angled high in a mighty leap.

The Elvis Connection

As their reputation grew, the family band began to notice a young white kid at their shows, watching Calvin’s moves like a hawk. As Calvin recalled to Gordon, “I would see him everywhere, he used to come over to the Plantation Inn Club when we was over there.” That kid was Elvis Presley.

“Elvis used to be there, show up every Wednesday and Friday night to see me do Calvin’s Boogie and Junior’s Jive. I’ll be flyin’ and slidin’ across the dance floor [laughs] and I think that’s when he … started to flyin’, too.” Almost as a footnote, Calvin adds, “but he went on and made all that money, made millions of dollars, and I went to the jazz mountaintop and almost starved to death.”

But through it all, Presley remained close to the Newborns. It went far beyond studying their moves and their sounds at the club, as Calvin’s daughter, Jadene King, tells it. In describing her father’s prolific writings, she notes that he penned an as-yet unpublished volume with “a lot of the history between him and Elvis in it.” Titled Rock ‘n Roll: Triumph Over Chaos, “there’s an enormous amount of unspoken-of history of my dad and Elvis’ relationship. Actually, Elvis’ relationship with my entire family,” King says. “A lot of people think he was a prejudiced kind of human being, and from a very bigoted family, but that’s not true. He spent a lot of his life with my father and my uncle, at my grandmother’s home. They were very close. He ate many meals with my dad and my uncle, and my dad was the one that was responsible for a lot of his moves and a lot of his musical talent, as far as teaching him a lot of what he knew. They were very close.”

The Jazz Mountaintop

Family and Elvis aside, Calvin was more concerned with climbing to the jazz mountaintop, especially once the extent of Junior’s deep genius on the piano became widely known. After brief stints in college and the army, Junior was back in Memphis when Count Basie and the great talent scout John Hammond happened to visit, and heard him play. In that moment, the ring of opportunity became the death knell for Finas’ dream of a family band. By 1956, Junior and Calvin had moved to New York, playing in a quartet with two legends-to-be, Oscar Pettiford and Kenny Clarke, and recording for Atlantic and RCA.

Before long, Junior would go his own way, and deal with his own demons, leaving Calvin to deal with his. At first, the jazz mountaintop offered an escape from the South’s rampant racism. “I think that’s the main reason why I left Memphis, you know,” he told Gordon, “to play jazz. Because jazz seemed to have put it on an even keel, because a lot of white people respected jazz. And that was the bebop era, you know, and I admired Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday and all the jazz artists, so I was, that’s one reason I was so glad to get away from Memphis.”

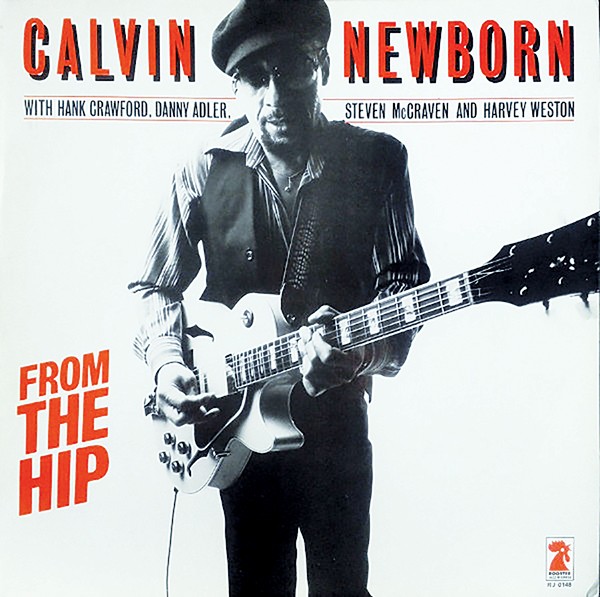

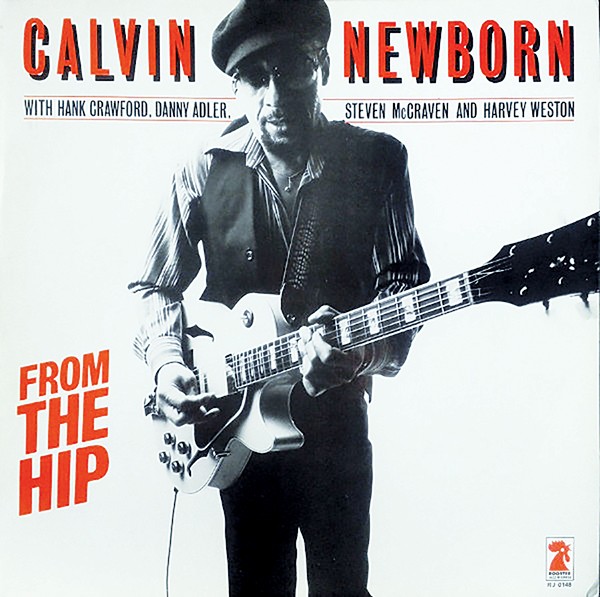

But he also fell into the traps of bebop life, as did Wanda. As Booth writes, “Calvin began working with Lionel Hampton, then joined Earl Hines. His wife, who had become a narcotics addict, had convulsions and died in her sleep, and Calvin began using heroin himself.” And yet, he managed his addictions well enough to keep playing, building his reputation every step of the way. As the 1960s wore on, Calvin ended up working with Jimmy Forrest, Wild Bill Davis, Al Grey, Freddie Roach, Booker Little, George Coleman, Ray Charles, Count Basie, Hank Crawford, and David “Fathead” Newman.

Meanwhile, Junior’s eccentricities were turning into full-blown mental anguish, and he spent time here and there in mental institutions, recovering from his alcoholism in hospitals, or simply convalescing in the family home. Still, he would perform and record.

In 1965, Finas, now suffering from heart problems in spite of his then-clean living, ignored his doctor’s warnings against performing and joined his eldest son onstage in Los Angeles. It was the closest he’d come to recapturing the Newborn family band’s glory days. And he died of a heart attack as soon as he walked off stage. Still, Mama Rose kept her home in Memphis, and Junior stayed there more and more.

Thus was the state of his life and his family when Calvin returned to see Beale Street in ruins. He was once again based in Memphis, but toured often. As his daughter recalls: “The first thing I remember as a little girl was him being in the Bubbling Brown Sugar tour. That had him over in Europe for several years, and he lived in Holland, London, Paris.”

King, whose mother was an Italian immigrant whom Calvin met at Coney Island, but who grew up in Jacksonville, goes on: “That’s my first memory of daddy being gone for a long period of time. That was in the mid-1970s. And he did that for a while. He was constantly gigging and touring during most of my childhood, but he would always come to Jacksonville to see me, or I would go to Memphis and spend time with him at my grandmother’s house. Mama Rose’s.”

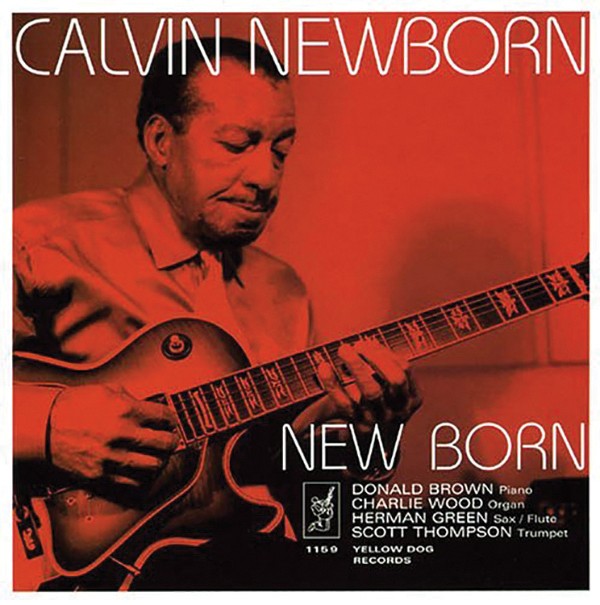

Staying at the family home or on his own, Calvin would help with Junior’s care and began playing more with his old classmate, Herman Green. The quartet recordings they made as the Green Machine still stand as some of the finest jazz that Memphis has produced. As the 1980s went on, Calvin joined Alcoholics Anonymous, cleaned up his act, made the occasional solo album, and began working with younger musicians. When Green fell in with the funk/rock/improv group FreeWorld, Calvin was not far behind. “Calvin was a member of FreeWorld for about two years, and his guitar virtuosity brought us all up several levels, musically speaking,” says FreeWorld founder Richard Cushing. “Herman and Calvin would occasionally start playing off each other in the middle of a song, pushing each other, cutting heads as only two old-school masters can do.”

Mike Brown

Mike Brown

Working in the studio.

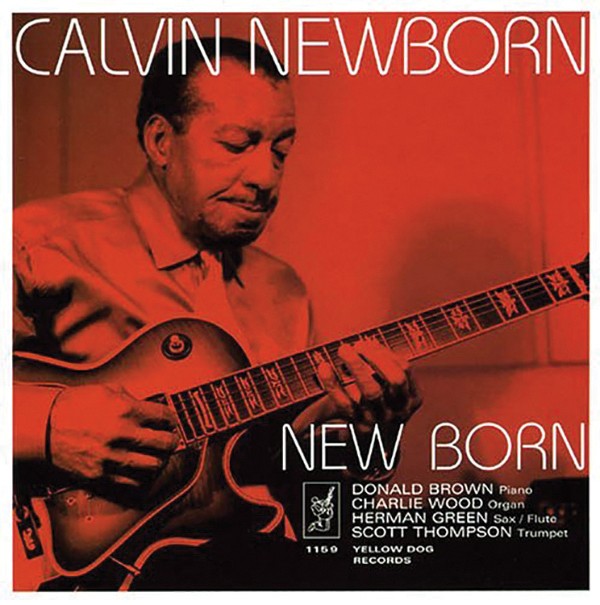

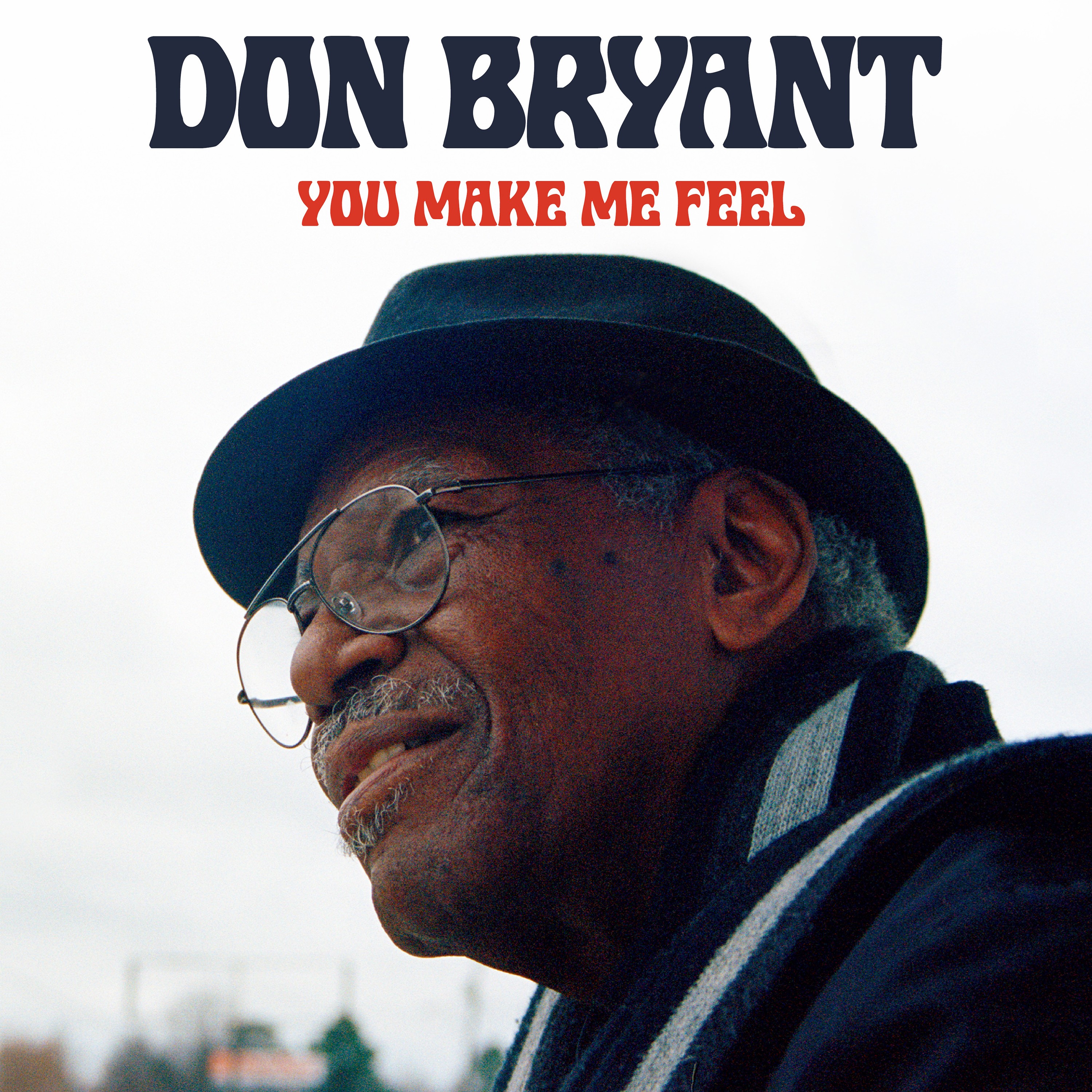

New Born

Memphis musician and producer Scott Bomar also treasures his time with Calvin, first as pupil and then as the producer of his phenomenal album, New Born. “I had to put a band together to back Roscoe Gordon, and I asked Calvin to play guitar. That was the beginning of our friendship and the beginning of us doing gigs together. Some of the most amazing musical settings that I’ve had the good fortune to be part of were with Calvin. At one Ponderosa Stomp show, the Sun Ra Arkestra actually played with Calvin and me. That’s one of the most intense audience reactions I’ve ever seen at a concert. And every time I’d talk to Calvin, he would still talk about it. The last time I spoke to Calvin, he was still talking about that performance. It was a tune of his called ‘Seventh Heaven,’ and that was a very, very special performance.”

Even as the next century approached, Calvin had a flair for showmanship. Bomar goes on: “When he got on stage, he had this energy that not many people I’ve ever played with have. He was electric. He could hit his guitar in a way that got people’s attention. His tone — I love his rawness. Of course, he had this deep musical knowledge and was very melodic, but he also had this kind of raw, rock-and- roll edge to his tone and his playing. His tone was always on the edge of distortion.”

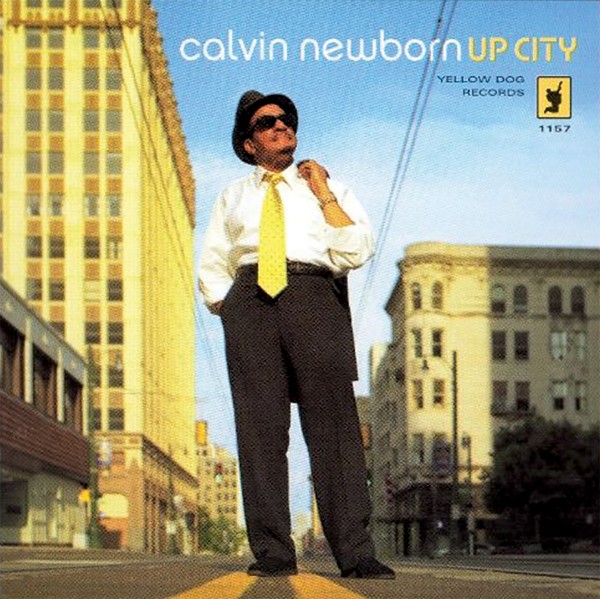

By 2003, there was less to keep Calvin here in Memphis. Junior and his mother, Mama Rose, had left this mortal coil behind. And so he settled in with his daughter, adapting to the Sunshine State and a more contemplative life. “My dad had various levels of spirituality, and he studied every religion known to man. He studied Islam, he studied Jehovah’s Witnesses, he studied Judaism, he studied Hinduism. My father was just a brilliant individual. He’s read the Koran three or four times. He’s read the Bible many times. He was just a very well-versed man, and I would say the last 10 years of his life he completely went over to Christianity.”

Calvin also continued to perform at the Jazzland Cafe and the World of Nations festival in Jacksonville, not to mention many area churches. And he remained as feverishly creative as ever. “He has several unpublished compositions that I have,” notes King. “I have several plays, several books, and tons of lyrics and scores for new music, new songs. He had just finished scoring a musical project that he wanted to take to New York and record.”

And then, in the spring of this year, romance came back into his life, in the form of one Marie Davis Brothers, who he had known for decades. “I’ve known her my whole life, for over 43 years,” says King. “Originally, they were together for 12 years, and they separated and were apart for 20 more years. In 2017, they started communicating again. They’d been talking over the phone for a little over a year, and then in April she moved here from Memphis. And in May they got married and they moved into their own apartment.”

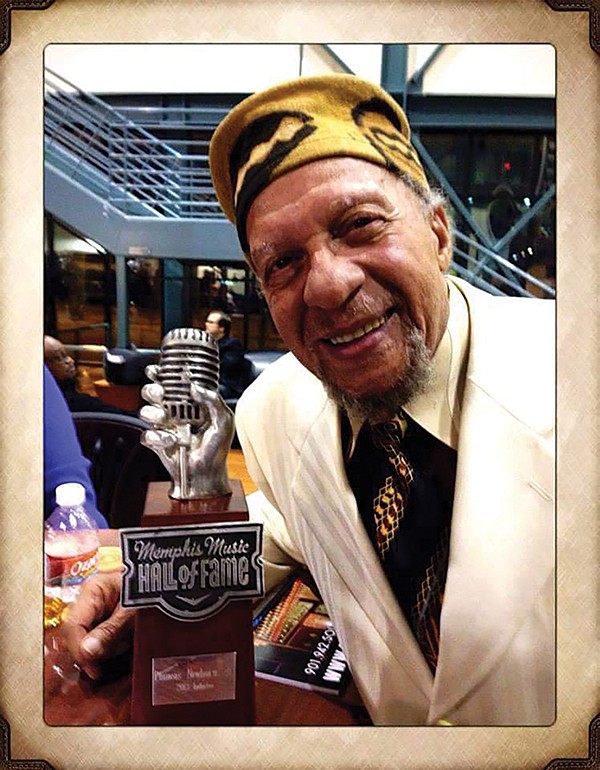

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

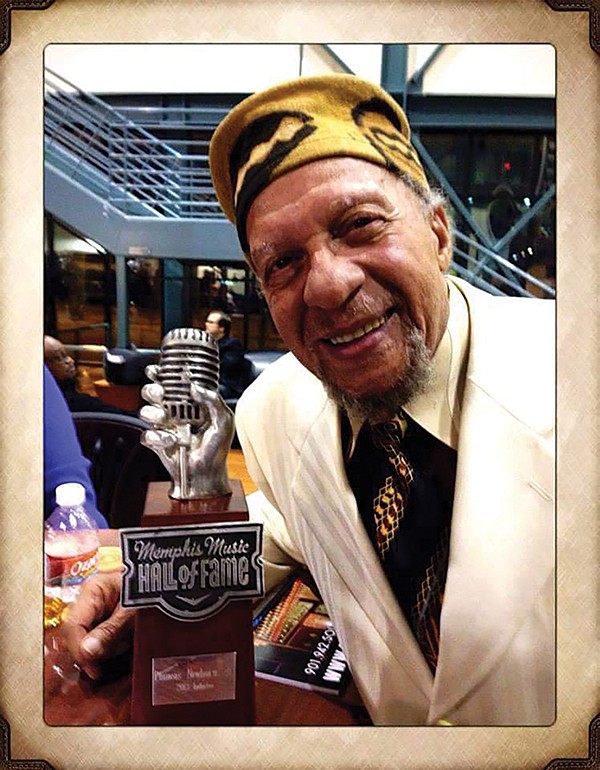

Calvin Newborn at the Memphis Music Hall of Fame induction of his brother Phineas.

The Final Chapter

No one expected Calvin Newborn to die this month. “He had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) from the years and years and years of smoking and drinking and just the jazz life, but he’d been sober and clean for over 35 years, and he was doing very very well,” says King. “Just in the beginning of November, his oxygen levels weren’t what they needed to be, but he just went from not having oxygen to wearing a little Inogen [portable oxygen] machine. And then toward the end of the month, that stopped giving him the levels that were needed, and here we are.”

Just before the end, he was still giving his daughter new writings to type up. “In my father’s last couple of months, he wrote a poem called ‘Seventh Heaven.’ It was based on a dream where he saw his great-granddaughter, who he called Bliss, looking out into what he called seventh heaven, and everyone was at peace. There was no more hatred, there was no more racial divide. There was no more poverty. Everything had been leveled out. It was a beautiful world. I guess if my father had an epitaph, it would be ‘Seventh Heaven: There’s no race, just the human race.'”

In Calvin Newborn’s heaven, there’s room enough for everyone to fly.

Darnell Henderson II

Darnell Henderson II  David Patten Mason

David Patten Mason  Billy Fox

Billy Fox  Margaret Deloach

Margaret Deloach

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Christian Patterson

Christian Patterson  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King  Steve Roberts

Steve Roberts

Mike Brown

Mike Brown  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King