New York, Rome, and London each have more outdoor sculpture than you can view in a month of sightseeing. Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston are rife with it. Even other cities our size, like Kansas City, host plenty of publicly accessible sculpture, nestled in plazas and city parks or proudly situated outside museums, on college campuses, and at corporate headquarters.

After a long drought, Memphis is trying to catch up.

Keep your eyes peeled at certain intersections, and you’ll catch a glimpse of a bronze statue here or an iron form there.

On South Mendenhall, a 15-foot stone Buddha graces Henry Chu’s front yard, easily dwarfing the pink flamingos, St. Francis statues, and ceramic garden gnomes that stand guard over the rest of the neighborhood.

In Overton Park, a doughboy statue and a monument to E.H. Crump serve as sentinels, and pieces by Jacques Lipchitz, Jim Buckman, and George Rickey dot the landscape outside the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art. Ted Rust’s bronze sculpture, IKON, marks the entrance to the Memphis College of Art and concrete animals line the entrance to the Memphis Zoo.

Brian Russell’s giant aluminum ballerinas pose atop Ballet Memphis’ Cordova facility, and Lon Anthony’s work stands tall on the Rhodes College and University of Memphis campuses. At the corner of Union and Manassas, a bronze statue of Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest draws the admiration of some and the ire of others.

While most local works are figural or representational, there are a few abstract sculptures in the mix, including French sculptor Armand’s 30-foot-tall, 15,000-pound bronze Ascent of the Blues, erected outside the Morgan Keegan building on North Main Street in 1987. A few years later, the $250,000 piece, which was welded together in three places, unexpectedly collapsed, leaving one worker hospitalized. After the mishap, it was unceremoniously dumped into long-term storage.

Although Chicagoan Richard Hunt’s low-slung, steel Martin Luther King Jr. tribute, I Have Been to the Mountaintop, installed on North Main Street in 1977, has proved more lasting, it’s also doubled as a skateboard ramp for urban teens and a canvas for aspiring graffiti artists.

Memphis sculptor John McIntire’s 20-foot-tall, 10,000-pound concrete work, The Muse, has suffered similar indignities. Built in the mid-1970s for just $2,000, the sculpture was originally planned for a leafy copse outside City Hall, although it’s been moved twice in the last three decades.

“The architects put me way down by Goldsmith’s on Main and Gayoso,” recalls McIntire, who worked as a professor of sculpture at the Memphis College of Art from 1961 to 1985. “The ground wasn’t stable, and the sculpture tilted. We went over there with railroad jacks in the middle of the night and tried to dig beneath it, but we hit water, so we filled the hole and left.

“About five years ago, the mayor’s office called and told me they were gonna move it,” McIntire says. “They wanted me to stand out there with a hard hat and supervise. They used cranes to move it in front of the Federal Building, standing it on a concrete base that went five or six feet below ground.

“A year ago, they called and said they wanted to move it again,” McIntire continues with a chuckle. “I reminded them what it weighs, and they said, ‘Oh, thanks for telling us.’ I never heard from them again.”

Today, the UrbanArt Commission, established by Kristi Jernigan in 1997, oversees most pieces in the public eye. In their nine years of existence, they’ve funded 60 public art projects, approximately half of which are sculptures.

The Ballet Memphis commission, Jill Turman’s Cooper-Young Trestle, the sculptures by Garrison Roots and Brad and Diana Goldberg at the entrance to the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library, Vito Acconci’s steel form outside the Cannon Center, Yvonne Bobo’s solar-system constructions at Peabody Park, and John Medwedeff’s shade structure in Vance Park were all created under the aegis of the UrbanArt Commission.

“Public sculpture,” says the organization’s executive director Carissa Hussong, “requires stopping and thinking. Once you allow yourself to interact with the work, it takes on a new meaning.”

For many Memphians, however, the very concept of public sculpture is defined by controversy. When the city opened the doors of its new main library, people talked more about Explicitus Est Liber, the public sculpture in the facility’s plaza, than they did about the building itself. The hullabaloo centered around the etchings on the series of standing and broken granite columns, including illustrations of spermatozoa, and an excerpt from the Communist Manifesto. City councilman Brent Taylor and county commissioners Tommy Hart and Marilyn Loeffel spearheaded efforts to sandblast the artwork, but the UrbanArt Commission persevered.

Acconci, a world-renowned sculptor, got a similar reaction when he unveiled Roof Like a Liquid Flung Over the Plaza, the steel structure that flows unfettered from the southwestern corner of the Cannon Center. Part sculpture, part shelter, the work has been labeled an eyesore and a waste of taxpayers’ dollars by amateur art critics.

“The issue is, what do you define as public art?” asks artist Greely Myatt, who has taught sculpture at the University of Memphis for nearly two decades.

“There’s the idea that as public art, it’s understood by the public, but it’s not always speaking the public dialogue,” insists Myatt, who has permanent work on display at AutoZone Park and at a Tennessee Welcome Center on I-40. “Yet, if you water down the work, you’ve got mall art.”

No single piece of public sculpture can please everyone, Hussong admits. “The library project drew so much controversy, but the plaque that said ‘Workers of the world, unite!’ was just a small portion of the full artwork. In some ways, that piece negates controversy, because it reflects the good and bad of our history. It shows a more complete picture of humanity.”

According to project manager Elizabeth Alley, the UrbanArt Commission oversees as many as 30 public art projects at any given time, which last, on average, for three years apiece. Working with the city’s capital improvement budget, the commission divides projects by districts and creates a selection panel for individual projects, 60 percent of which will be awarded to local artists.

“We also have education programs for local artists to help translate their studio work into public art,” Alley adds.

“Aside from the public sculpture projects, we’ve got art spread through schools and community centers all over the city,” says Hussong. “Neighborhood groups come to us, and we work with MATA and other nonprofits.”

She says the commission focuses on “good, long-term work” — public landmarks like the sculptures in Vance Park and Peabody Park and gateway projects like the Soulsville murals on Bellevue Boulevard, the Glenview Community Center gates on Lamar Avenue, the Cooper-Young trestle art, and the Orange Mound neighborhood signs.

“My philosophy,” Hussong says, “is that the success of a project comes when the community embraces it and feels like it’s theirs. To have a healthy program, we need to look at more than diversity, subject matter, and medium. We need to ask, Is this an icon? Is this a community-builder? How does the audience interact with the piece?”

For many local sculptors, other, more basic concerns override questions about audience interaction.

Artist Terri Jones, who designed Recognize, a work saluting donors that’s on display in the Cannon Center and a similar piece at Bridges’ nonprofit headquarters, worries about maintenance issues like lighting and landscaping, always the first to go when local government makes budget cuts.

Privately funded sculptures pose other problems as well. Mark Nowell’s The Open Container was commissioned by Towery Publishing owner Bob Towery and then left at the corner of Union and McLean after the company closed. Jones questions who remains responsible for the work.

“As far as I know, it’s in a no-man’s-land,” she says. “But every time I drive by, I wonder, Does it belong to Bob? Does it belong to Mark? Or does it belong to the property owner?”

Misguided decisions can devalue public art in question, says Myatt, Jones’ husband. He relates the case of an Alexander Calder sculpture located in a Pennsylvania airport. “They changed its color to match the décor,” he says indignantly. “When is that appropriate?”

Sculptor Roy Tamboli chooses to avoid the public sector altogether, instead working on private commissions or creating self-financed work like the 25-foot steel structure called Pangaean Disc, installed near the Poplar viaduct on a lot owned by Memphian Lou Loeb.

“I’m homegrown, self-produced, and privately funded,” Tamboli proudly states. “A lot of people are waiting for the government to do everything, but that’s not the most efficient way to work.”

His theory seems to be successful. He currently has 30 bronze sculptures that are being cast at three different foundries, all for private commissions. Nevertheless, Tamboli, who recently created a bronze piece for the Dixon Gallery & Gardens, also sees the value in publicly displayed work.

“When you see a piece of art in a public space, it stimulates an area of the brain that hasn’t been explored before,” he notes. “The irrationality stimulates other creative thinking, and it creates a chain reaction. A lot of commissioned work is almost like exterior decoration — it’s more exciting when it really stands on its own.”

McIntire also survives on private commissions, like the stone sculptures he’s carved for the French Quarter Inn hotel chain and a piece he created for the University of Tennessee’s medical center. “Back in 1965, I also created the world’s largest plaster Jesus, for Elvis’ bodyguards, who wanted to get [Elvis] a special Christmas present,” he says.

“I did it in one week,” he recalls of the religious icon, which dominates the Meditation Garden and family cemetery at Graceland. “I think more people have seen it than have seen Michelangelo’s statue of David — and it’s the worst sculpture I’ve ever done,” McIntire sighs.

“I hope that in 10 years, we’ll see more sculptures in Memphis,” Hussong says. “I’d love to see more community interest and support. I’d like to see more privately funded projects and more commitment on the part of corporations and developers.

“There’s a general trend of architectural sameness,” she says, “and public sculpture helps establish a sense of place, an identity.”

TOP 10 PUBLIC SCULPTURES in memphis:

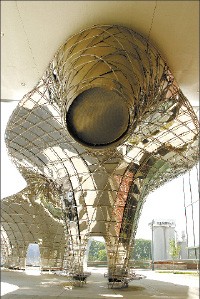

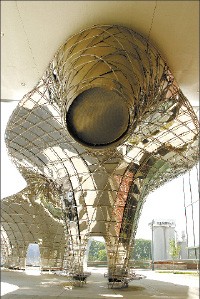

Vito Acconci, Roof Like a Liquid Flung Over the Plaza (The Cannon Center, 255 N. Main Street)

You either love it or hate it, but either way Vito Acconci’s steel piece elicits a visceral reaction. Originally, says UrbanArt Commission executive director Carissa Hussong, who green-lighted the project, Acconci planned a $5 million structure that would wrap around the Cannon Center. Because of budget issues, she says, “he whittled it down to the current fabrication, which cost $550,000.”

For fans like artist Terri Jones, the price was a steal. “The piece is about pulling down the sky and pushing the earth up,” she explains. “The movement of the clouds and their reflection in the material are just beautiful. And you can enter the space and sit in what is a very democratic seating arrangement. There’s no hierarchy.”

Yet Jones’ husband, U of M sculpture professor Greely Myatt, declares, “I don’t care how democratic the seating is — I’ll bet it’s hot in there.” Surveying the homeless people who often seek shelter inside the sculpture, former Memphis College of Art professor John McIntire dryly adds, “Yep, it’ll cook ya!”Yvonne Bobo, Without Boundaries and Solar System (Peabody Park, Cooper Street at Higbee Avenue)

On the flipside, local metalsmith Yvonne Bobo (who is also known as the muse for her musician ex-husband, Harlan T. Bobo) has received rave reviews for her whimsical additions to Peabody Park and the Skinner Community Center. Built last year with funding from the UrbanArt Commission, Without Boundaries, an arched entrance created from concrete and metal, features planets that spin playfully in the breeze. The archway points visitors toward the fountains, water sprays, and another sculpture, a steel model of the universe called Solar System. The interplanetary theme continues with Our Sky, a glass installation Bobo designed for the community center’s pool area. Once a drab patch of grass nestled beneath a railroad track, Peabody Park is now a gleaming jewel in the heart of Midtown.

Richard Hunt, I Have Been to the Mountaintop (North Main Street, between Poplar Avenue and Exchange Avenue)

“People look twice, wondering what this piece is,” notes Hussong, “but I consider it one of the best examples of public sculpture in Memphis.” The welded steel sculpture, dedicated to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was commissioned by the Mallory Knights charity organization and installed in downtown Memphis in 1977. Described as “part altar, part pyramid, and part playground,” Hunt’s piece is just 12 feet high, but it sprawls across 40 feet of ground, making it a perfect launching pad for skateboarders. Weathered by the elements and occasionally threatened by various urban renewal projects, I Have Been to the Mountaintop has, like King’s legacy, persevered.

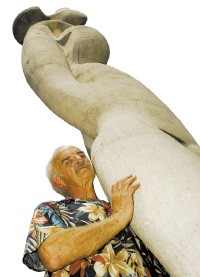

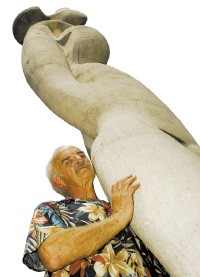

John McIntire, The Muse (North Main Street, between Poplar Avenue and Exchange Avenue)

“Look at an abstract sculpture, and you won’t see the same thing twice,” McIntire guarantees. Glancing up at his concrete sculpture, which rises 20 feet above North Main Street, you’ll see a woman with a basket on her head, a mother carrying a child, a towering totem pole, or a more rounded version of Marcel Duchamp’s surrealist painting Nude Descending a Staircase, rendered in rough three-dimensional form.

“The architects kept wondering when I was gonna polish it,” McIntire wryly jokes, noting that he was paid just $2,000 for the piece, originally installed on Main Street near Gayoso in the mid-1970s. Since then, The Muse has been relocated twice. It’s been in its current location outside the Clifford Davis Federal Building for just a few years. “It gets lost where it is now,” Hussong frets, “but it’s impossible to move.”

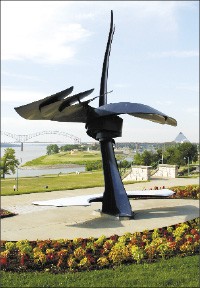

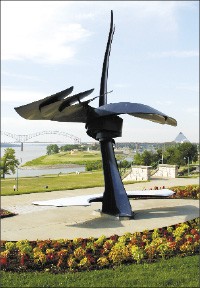

John Medwedeff, Whirl (Vance Park, Vance Avenue at Riverside Drive)

John Medwedeff won a national competition for this project when he was in residence at the National Ornamental Metal Museum. The 18-feet modernist whirligig, simply called Whirl, was installed near the Riverwalk in the summer of 2001. Since then, the metalsmith has created work for the Sarasota, Florida, Judicial Complex, Courthouse Square in Clarksville, Tennessee, and Southern Illinois University’s School of Engineering.

The Illinois sculptor, who says that he transcends conventional boundaries with his metalwork, forged painted steel to mimic the wind and water that whip the South Bluffs.

Mark Nowell, The Open Container (1835 Union Avenue at McLean)

Employees of the now-shuttered Towery Publishing often referred to this gleaming steel piece, commissioned by former company owner Bob Towery, as the “Moon Pie.” Towery closed its doors approximately a year after The Open Container was installed, leaving curious passersby to decipher its meaning and, ultimately, its providence.

The sculpture has long been a target for graffiti artists, including one miscreant who scrawled “Fuck Corpret [sic] Art” on one side in March 2001. “I’ve always responded to its relationship to the building,” says sculptor Greely Myatt. “What amuses me is that one of the pieces is a twisted communications tower,” he adds, noting in the next breath that Towery was a failed communications company.

Garrison Roots and Brad and Diana Goldberg, Explicitus Est Liber (Benjamin L. Hooks Public Library, 3030 Poplar Avenue)

Under the aegis of the UrbanArt Commission, 11 artists combined forces to create work for Memphis’ new central library. But when the project was unveiled in 2001, just three sculptors, Roots and Brad and Diana Goldberg, felt the wrath of the City Council. When Councilman Brent Taylor and county commissioners Tommy Hart and Marilyn Loeffel decided to have an excerpt from the Communist Manifesto excised from the work (the offending words extolled, “Workers of the world, unite!”), even The New York Times reported on the battle. Score one for the liberals. Today, Explicitus Est Liber, a series of granite columns and slabs which bring to mind images of both the ancient Alexandrian library and a post-modernist future straight out of Logan’s Run, stands intact.

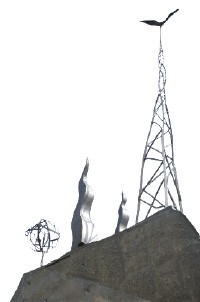

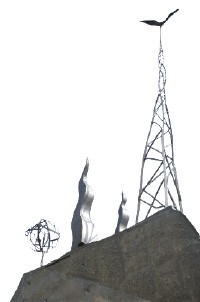

Brian Russell, The Virtues (Church Health Center, 1196 Peabody Avenue)

This set of 10-foot cast glass and aluminum sculptures appeared in November 2004. Russell, a furniture maker and sculptor, creates more than 100 works a year, including pieces belonging to Rhodes College and the Tennessee State Museum and an installation for Ballet Memphis. By day, The Virtues serves as a landmark, a reminder of the Church Health Center’s spiritual mission and a memorial to a major donor. By night, the sculptures softly glow, providing a beacon for neighbors and staff.

Ted Rust, IKON (Memphis College of Art, 1930 Poplar Avenue, inside Overton Park)

The local art world owes a lot to sculptor Ted Rust, who served as director of the Memphis College of Art for 26 years, beginning in 1949. Under his supervision, the school, called the Memphis Academy of Art at the time, relocated from Adams Avenue to its present home in Overton Park, attracted world-renowned teachers (including fellow sculptor John McIntire), and increased its budget nearly tenfold.

Between his administrative duties, Rust found time to create numerous sculptures, including commissions for Idlewild Presbyterian Church, Temple Israel, and Rhodes College, and exhibit other pieces at such places as the Carnegie Institute, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. IKON, a tree-like, 11-foot brass sculpture, was unveiled outside MCA in December 2001 to commemorate Overton Park’s 100th anniversary.

Roy Tamboli, Pangaean Disc (Union Extended at Walnut Grove Road)

Commute down Union Extended often enough, and you’ll find yourself contemplating the meaning of Pangaean Disc, Tamboli’s giant globe/sundial that sits on a slope of land just north of the Poplar viaduct. “Pangaea was the original super-continent, before the world became as we know it today,” explains the Midtown-based artist, who installed the steel structure on private property in 1992.

“I think you can enjoy it driving by,” he says, although by anyone’s definition, the piece deserves a closer look. Pull off the road, get out of the car, and find the plastic baby dolls, which sit in fragile contrast to steel and earth. “People who look at the capsule think it’s pro- or anti-abortion, but really, it’s neither,” says Tamboli. “The dolls give it that voodoo-folk, outsider statement. I didn’t want it to be too pretty.”

Lost in Translation

From Italy to East Memphis, public art goes to the mall.

It’s easy to understand why malls, which want to attract as many shoppers as possible, shy away from controversial public art. Consequently, it’s no surprise that most of Memphis’ mall sculptures are idealized representations of weirdly nonracial children in vaguely 19th-century clothing forever frozen in the wholesome acts of jumping, biking, swinging.

In fact, Oak Court and Peabody Place both have the exact same sculpture of three girls skipping rope, which should be a portrait of innocence, but due to the figures’ lipless, alien features feels more like an outtake from Village of the Damned.

Artwise, Wolfchase Galleria had the right idea when it commissioned established Memphis artists such as Pinkney Herbert and Alonzo Davis to create original, decorative pieces. And sculpturally speaking, it’s hard not to love a gaudy carousel. Technically, the carousel isn’t high art, but you can’t knock the existential beauty of watching people of every age, shape, and size going around in circles.

Likewise, what’s not to love about the giant spinning marble ball that greets visitors at Oak Court? It elegantly blends the thrills of an Indiana Jones movie with the kitchyness of one of those novelty spigots that seem to produce water from nowhere. Oak Court also houses a provocative unnamed bronze miniature depicting male and female figures clutching the shaft of an umbrella when it’s clearly not raining. It’s romantic bordering on bawdy. It goes with the Sunglasses Hut like a $9 Merlot goes with SpaghettiOs. It’s junk, but you know you love it.

Peabody Place may be a hodgepodge of architectural whimsy, but it also houses the one piece of sculpture worthy of a magnificent Renaissance piazza (the origin of our modern-day mall, lest we forget). In the middle of all the loud silliness, there’s a large jade sculpture of horses rearing up. Full of emotion and life, this piece seems out of place but loses little dignity by being reduced to an advertisement for the Peabody Place Museum. — Chris Davis