The annual big freeze seems to have gone, but what could have dispensed with the cold Memphis weather? Perhaps it’s all the love in the air. With Valentine’s Day fast approaching, be uplifted by the stories of three Bluff City couples who navigated their own twisty, windy paths to love. Their tales will thaw both the frostiest days, and our cold, frozen hearts.

Justin J. Pearson + Oceana R. Gilliam

Oceana Gilliam says she met Justin Pearson in 2016 at Princeton University. “Justin and I, we both did this program together called the … what is it?”

“Policy International Affairs Junior Summer Institute,” says Justin, finishing her thought, as the couple are prone to do.

“We were both juniors in college going into our senior year,” Oceana continues. “I was really smitten, I think, when I first saw him, because even then, when we were just in college, he would have on his suit. When he would introduce himself, he would stand up and say, ‘Hello, I’m Justin J. Pearson.’ I was just like, oh my God, I really love that. He was always so kind. He’s always so sweet.”

“She was this very cute Black girl who was speaking Russian and singing in Russian at this program,” Justin recalls. “There was a song that I had just learned by Leon Bridges. One of the lines is ‘Brown skin girl with the polka-dot dress on.’ I love the song and I remember sending that to her, so I liked her a lot.”

Oceana, who was “born and raised in South Central,” Los Angeles, went to grad school at UCLA, while Pearson was all the way across North America at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, before leading the charge to stop the Byhalia Pipeline with Memphis Community Against the Pipeline. (After their victory, the environmental justice organization changed its name to reflect a wider focus on pollution.) “Even though we didn’t get together, it’s like the flame never went away,” says Justin. “Which is why I kept pursuing, probably more than she was. I was in the DMs between 2016 and literally 2020.

“We reconnected because I actually went to L.A. and I saw her for 30 minutes before I gave a speech. She was in grad school at UCLA getting her master’s in public policy. And so anytime I would talk to her — which was very little over those few years — she was just doing some amazing stuff for policy and political science things. But then we had Covid, and we had the summer of Black Death with George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, these lynchings going on. She was protesting a lot in Los Angeles, and I was starting to get more engaged and involved in things in Memphis because we just moved back home. Then we had the pipeline fight in Memphis, and we really started to connect and bond and talk. She was a big support system during that time, too.”

“We really, really connected during the pandemic — we’re one of those pandemic bae couples,” says Oceana. “It was such a difficult and hard time. He was someone that I could really turn to, and he was always there for me. … We would literally be working with each other — I’ll be on a work meeting, he’ll be on a work call, but we have our Zooms on or our FaceTime on mute. We spend hours and hours together.”

When Justin broached the subject of running for the Tennessee House of Representatives to Gilliam, “At that point I could really see it,” she says. “He was already doing a lot of great work with MCAP, and I saw how he spoke out against trying to build this pipeline between people’s homes and take land. And so when he decided to say, ‘Hey, I want to run for office,’ I was with him fully and completely. I feel like that was a great path for him. He’s really passionate about this work, but he’s also very genuine. He’s very serious.

“Just from my own experience, being around other type of politicians, what I really appreciate about Justin the most is that the work that he does, he really does it from the heart. After going around with him, door knocking, meeting people in Westwood and other parts of Memphis and Millington, people really, really love Justin.”

As Justin grappled with the decision to run for office, the couple took a road trip from L.A. to Memphis. “You’re on the diving board and you’re like, am I really going to jump? We kept getting all these signs that this is the right thing to do. I remember, I was driving and I was like, ‘We going to do it, right? We going to do it? We were in Texas, and this huge cross kind of appeared out of nowhere, seemingly. And it was like, yeah, we’re going to do this thing.”

After Justin won a special election in 2023, Oceana was going to return to Los Angeles, but instead got caught up in what Justin calls “the most wild week ever known to humanity,” where he was sworn in to the house, brought the post-Covenant School shooting protests against gun violence onto the State House floor, and was then impeached and temporarily expelled from the Legislature. “That was such a difficult time,” she says. “I was in the gallery every single day with him. It was really something else.”

Justin and Oceana got engaged at her birthday party in 2023. They plan on tying the knot in the spring of 2025. “You get triumphs, or you get tragedies, that bring people together,” says Pearson. — Chris McCoy

Sepideh Dashti + Amir Hadadzadeh

Amir Hadadzadeh and Sepideh Dashti met some 10 years ago in Iran — they’d met a few times actually, but mostly in passing. Amir’s university friend married Sepideh’s sister, so they were bound to get to know each other one day.

At the time, Amir was studying in Canada, and Sepideh was still in Iran. On a visit back home, Amir had been tasked with dropping off something from his friend and his wife to Sepideh. “I knocked on the door,” Amir reminisces, “and someone — Sepideh — just opened the door a little bit and a hand came out, grabbed the thing, and went in. She didn’t even show her face.” This day, it turned out, wouldn’t be the day that Amir and Sepideh got to know each other, but they laugh about it now.

Instead, Amir says he kept thinking about her while he was studying for his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering. He was drawn to her seriousness. “She didn’t care about any guy. I mean, there was no one,” he says. “And then I decided to call, so it started from there.”

“Actually, we would chat [over Skype and Yahoo Messenger],” Sepideh corrects. “We were too shy to talk.”

But in 2009, the internet in Iran was not stable as the government sought to tighten its control. “We would start to chat with each other. And in the middle of the chat, the government decided to shut down the internet,” Amir says, “and we were not able to really have a deep conversation. It was very tough for us.”

“The internet shutdown happened,” Sepideh says, “and that was a moment we felt that [we would make a good couple] because then our conversations stopped for several days and I remember Amir’s sister called me and said, ‘Amir is very worried for you and asked me to tell you not to go outside because they arrested someone for protesting the election.’”

And so, Amir and Sepideh kept chatting, sending messages when the internet allowed, and eventually graduated to phone calls and video calls after the shyness wore off. After a few months, Amir returned to Iran and proposed. “She accepted,” Amir says. They had about a month together before Amir returned to Canada, and they could only see each other a few hours a day. “Sometimes we had to be sneaky,” Amir says with a smirk.

A year later, they were married. “We only had 10 days to be really close to each other [after the wedding before Amir had to go back to school],” Sepideh says. She was able to get her visa six months later, so they could finally be together in the same country. The day they reunited was April 15, 2011, Amir recalls immediately.

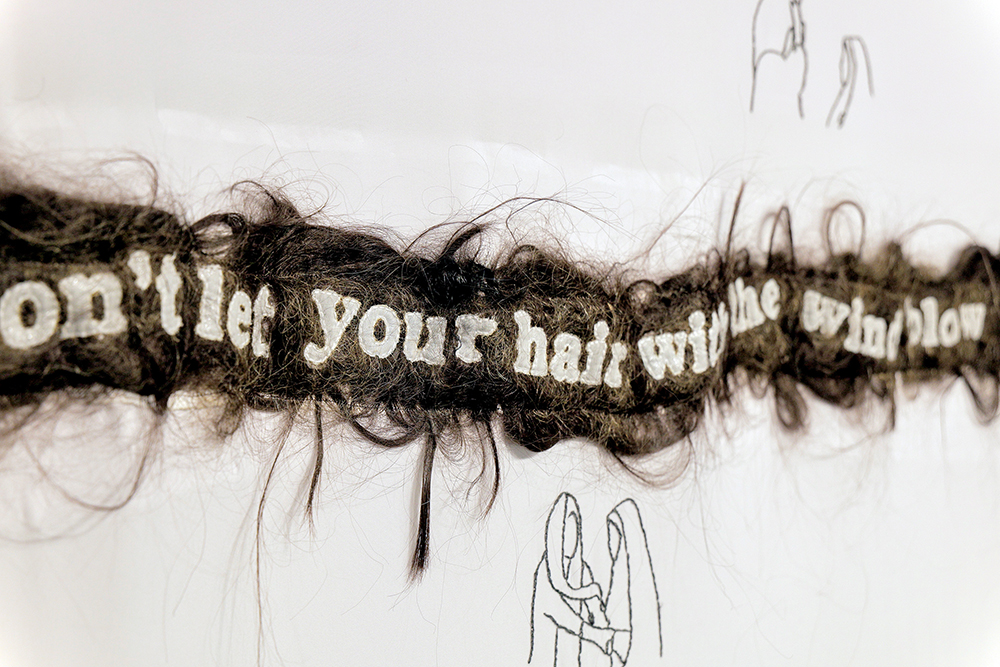

Since then, they’ve moved from Canada to Memphis, with Amir taking a job at the University of Memphis as a professor of mechanical engineering. Sepideh, meanwhile, is something of a multi-hyphenate as an art instructor at the Kroc Center, adjunct faculty at U of M, a Ph.D. candidate in educational psychology and research, and an artist who explores identity, womanhood, and the body. “I always tell her, ‘You are an internationally recognized artist. You should acknowledge that,’” Amir adds when he boasts about his wife’s accomplishments.

“He’s why I can manage,” Sepideh says, “especially with two kids. Honestly. … Like, even, I can say now in our parenting that we are very involved. So I’m very serious and I get mad and angry very easily, so most of the time I ask, ‘Can you manage this?’ I think his humorous sense has helped to engage with kids, make them calm, and make me calm.”

With both their families back in Iran, the two have found support and comfort in each other. “I think sometimes I feel this attachment is too much because when he goes somewhere for a seminar that is not in Memphis, I’m so stressed,” Sepideh says.

“We’ve imagined what would happen if we were back in Iran and discussed that a lot,” Amir says, “and we’ve concluded that we wouldn’t be as happy as what we have here. … I only wish that I would have met her earlier. That’s the only regret that I have. I wish we would have met, I don’t know, 10 years, at least five years earlier. [For now,] I’ll just admire her, love her, try to make her laugh.”

“We hope to grow old together,” Sepideh adds, “and watch our children become independent and lead fulfilling lives, just as our parents wished for us.” — Abigail Morici

Mario + Kristin Linagen-Monterosso

I happened to be present the moment sparks flew between Mario Monterosso and Kristin Linagen. As Kristin recounts it, “Mario asked a mutual friend about me, and she said, ‘You know, she’s single now, if you’re asking about her.’ And he reached out to me via social media and said, ‘Hey, I’m playing at DKDC tonight. I’d love to see you.’”

Monterosso, of course, is the celebrated Italian guitarist who moved to Memphis years ago to follow his dream of living in the birthplace of the music he loved most. He soon became an integral part of the roots music scene here. Last May, as James and the Ultrasounds, with me on keys, held court at Bar DKDC, Mario sat in with us and we all did a double take: He was on fire that night.

Yet it was Mario’s winning personality more than his musicianship that caught Kristin’s eye. “You know, it was fate,” she says now. “We went out for a couple cocktail nights, and then he said, ‘Hey, I’d like to take you out. I’d like to court you.’ And I’m a traditional woman, I’m old-fashioned, so I just loved that idea. I thought he was a cool guy.”

Kristin has an ear for music herself. “I love music,” she says. “I played the guitar growing up. I’m not much of a guitar player now, but I picked it up when we first started dating. Just to show him a little bit because I still remember all the songs I grew up playing in high school.”

While her real calling has been her own business, Therapeutic Touch Massage, opened after she studied at the Massage Institute of Memphis, Kristin clearly loves the arts. That may be why Mario decided that they must visit New York together. “After about a month of dating, he said, ‘Hey, I want to take you to New York,’” Kristin recalls. “It was June of last year, and we planned the trip for December. And we said, ‘You know, even if things don’t work out, we’re still going to go together.’ So we made a pact! I mean, we spit on our hands and shook on it and everything. You know, we go all the way!”

Mario smiles at this memory, then adds, “Being in New York with someone I love was always a big thing to me. But I’d never done it before.” Meanwhile, unbeknownst to him, his new amore had similar feelings about the Big Apple.

“Three years ago, I had this fantasy of being in New York with a man that I love over Christmas,” recalls Kristin. “And when he asked me to go, I thought, ‘Wow, this man is making my dreams come true. Are we making each other’s dreams come true?’ And by the time December comes along, and we’re all in, I’m thinking, ‘Okay, he loves New York. He loves me. Maybe he will propose?’”

She kept that to herself, though, as they embraced the city’s energy. “He took me to a Broadway show, Some Like it Hot,” Kristin recalls. “Then we walked to Rockefeller Center and experienced the crowd and the Christmas tree and Radio City Music Hall. And then we went to Sardi’s for dinner.”

After their meal, Kristin made a suggestion. “I said, ‘Let’s finish our wine upstairs, more privately, where we can look out the window at the Shubert Theatre. That’ll be fun!’ And of course he loves this idea, because it’s my idea, but he has things planned that I don’t know.”

That’s when Mario excused himself and pretended to visit the restroom. “It was the moment,” he says, “where I was thinking, ‘Do I do it now? Do I do it now?’ The ring was in my pocket!”

“He comes back and goes right into it,” says Kristin. “He just says, ‘Can I be direct with you?’ And he pulled out a red velvet box and said, ‘Kristin, will you marry me?’ I said, ‘Yes!’ And I ran up to the bar. ‘We need two glasses of champagne!’ Everybody applauded and we had a great evening from then on. And then the next morning, I woke up at 4 a.m. with a fever, shivering and sweating. I had gotten the flu!”

It was a perfect moment of “in sickness and in health,” and Mario dutifully cared for his beloved through the rest of their stay. By the time another month went by, Mario and Kristin Linegan-Monterosso had eloped. Nowadays, if you happen to see them, they’re likely to be beaming. — Alex Greene