As I watched The Get Down, I felt the slow realization that I don’t think Baz Luhrmann understands how narrative works.

Over the course of his 26-year film career, from the slick exploitation of Strictly Ballroom to his wildly overblown take on The Great Gatsby, he’s certainly proven he knows how to create spectacle. The Get Down is a vision of the birth of hip-hop as Olympian myth. Empowered by a free-spending Netflix, Luhrmann seems to have been encouraged to go more fully Luhrmann-esque than ever before. In his hands, the Brooklyn of 1977 is a hallucinatory war zone populated by characters of operatic breadth. The cast are all relative newcomers, led by Justice Smith as Zeke, a young poet whom we meet on the edge of becoming a proto-MC. His love interest is a singer named Mylene (Herizen F. Guardiola), and his mentor is a mysterious DJ named Shaolin Fantastic (Shameik Moore), and together they set out to conquer the world through tight flow and sick beats.

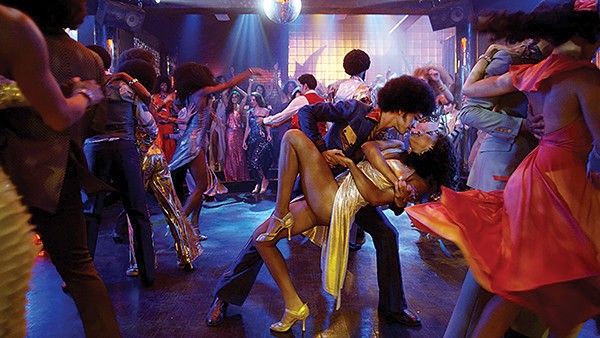

Justice Smith (left) dips Herizen F. Guardiola in The Get Down.

Or something like that. It’s really hard to fathom what is going on, plot-wise, at any given moment. Luhrmann seems incapable of concentrating on a storyline for more than three or four shots — and that’s only if there’s some kind of interesting movement taking place that he can track in some outrageous Dutch angle. He treats emotion the same way he treats color, splashing it across the screen for garish effect. Take his use of the great Giancarlo Esposito as Mylene’s father, the puritanical Pastor Ramon. Here’s an actor with superhuman control to spin a tapestry of conflicting emotion on his face, but Luhrmann sets him on one speed — “righteous rage.”

Lurhmann’s not using his actors to their full potential, but the same can’t be said of his production designer and cinematographers. The Get Down is one great frame after another, stuffed with detail, and connected by more whip pans and smash cuts than the 1966 Batman. It’s this manic inventiveness that’s always been the attraction to the director’s fans, and it’s here in spades. It might not be so much that the director doesn’t understand how to construct a narrative as he just doesn’t care. There’s no recognizable human psychology, but often The Get Down reads like one of the best long-form music video projects since Thriller. Letting the beautiful dancing people, the bumping soundtrack, and the hot-shot construction wash over is a pretty pleasant use of an hour or so, even if its lack of clear story renders it emotionally flat.