Two clear and vastly different story lines exist in the recent censure of Assistant District Attorney Thomas Henderson for misconduct in a capital murder case.

In the end, those differing opinions may be all that remain of Henderson’s part of a case that began 16 years ago and ended late last year. But maybe not. Some details of the case can’t yet be disclosed publicly. If they are brought to the surface, they may shed a new light on the entire saga.

Henderson was censured by the Tennessee Supreme Court’s Office of Professional Responsibility over the holidays. The office oversees attorneys in Tennessee and punishes them if they break ethical rules that govern the profession, as they did with Henderson.

The punishment the office handed down to Henderson is a “public rebuke and a warning to the attorney, but does not affect the attorney’s ability to practice law.” Henderson also had to pay the court costs that lead to the censure, which totaled $1,745.07.

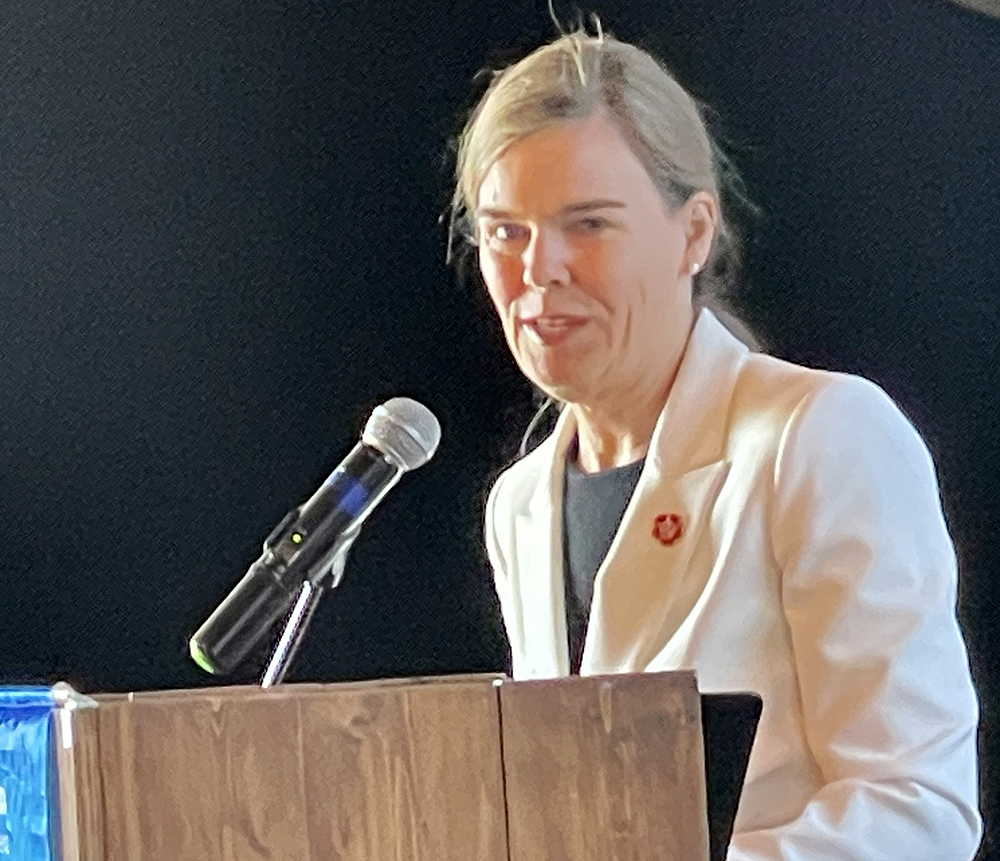

He and his boss, Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich, said he simply forgot about a piece of evidence in the capital murder case, that not disclosing it correctly was a “human error,” and his crime amounts to a clerical mistake. He pleaded guilty to the error, is enduring the public punishment, has to pay the fine, and the matter is closed.

Others, including judges and attorneys who spoke to the Flyer, said Henderson suppressed the evidence on purpose to win his case, and many doubted it was the first time he’d done it in his career. This kind of discipline against him has been a long time coming, some said. He got a slap on the wrist with a plea deal to probably save himself from being disbarred, attorneys said. Some criminal justice insiders said the matter has shaken faith in Weirich’s leadership, faith in the Shelby County District Attorney’s office, and even faith in the county’s justice system.

Henderson will keep his job in the Shelby County D.A.’s office, and Weirich said no further punishment is planned for the veteran attorney. She punished him, she said, by pulling him from the case associated with the censure.

“Those outside of this office may not understand what a punishment that is, but it was a huge step, and it was a tough conversation to have,” Weirich said. “We, as prosecutors, when we’re assigned a murder case — particularly a capital murder case — they become a part of us: the case, the family, and the victim.”

Thomas Henderson likely knows this like few others. He’s been a prosecutor in the Shelby County D.A.’s office since 1976. In that time, he’s overseen some of the county’s “most heinous and atrocious criminal cases,” a description often repeated by Weirich. He’s prosecuted hundreds of jury trials, at least 50 of them were capital murder cases. He now holds one of the top positions in the D.A.’s office, supervising some 50 prosecutors in Shelby County’s criminal courts. Weirich has called him a “dedicated public servant.”

The Flyer interviewed a number of Memphis attorneys who have had dealings with Henderson, many of whom were only willing to talk off the record. Some described him as having a prickly personality. Others had stronger words to describe a man, who they said, tries to (and does) get under the skin of his opponents with a stinging wit that seems intended to demean and humiliate. But all of the attorneys agreed that Henderson is razor-sharp, and it’s been said that if his critics needed a prosecutor for their family, they’d want him.

But Henderson keeps a low profile, despite his high-profile job. Google searches of his name turn up just a handful of news stories, most dealing with cases he’s prosecuted. Those searches yield only a couple of photos of the veteran prosecutor; they show a slightly balding, white-haired man with wire-frame glasses who sometimes wears a white mustache. The only direct contact the Flyer had with Henderson was in an email from him saying he could not comment on this story. He did not appear with Weirich in her press conference two weeks ago and was not made available for a photograph.

Beyond enduring news coverage of his public censure, there’s almost nothing more that could legally happen to Henderson. He was censured by the board that oversees his profession. Weirich, his boss and a duly elected official, has said repeatedly that she’ll stand behind him, and his job security rests with her.

To many outside the legal community, a censure may not sound like much. But it is. It’s but two steps away from disbarment (losing your license to practice) in Tennessee. “Enduring” a censure, as Weirich put it, surely means having everyone know that you — someone duty-bound and honor-bound to play by the rules — broke the rules.

“This one involves honesty to a tribunal, the courts, in a capital murder case,” said Memphis defense attorney Marty B. McAfee. “A defense attorney caught in dishonesty in a courtroom might well face jail for contempt of court and would surely be sanctioned by the Board of Professional Responsibility.”

The road to Henderson’s censure began about 16 years ago. It has spanned two highly publicized court trials, and Henderson argued them both. Paper files on the case would fill a room full of cabinets. The list of appeals and motions in the case are long and have occupied countless hours of time and thought in county and state courts for nearly all of those 16 years. But it all begins, of course, with a crime.

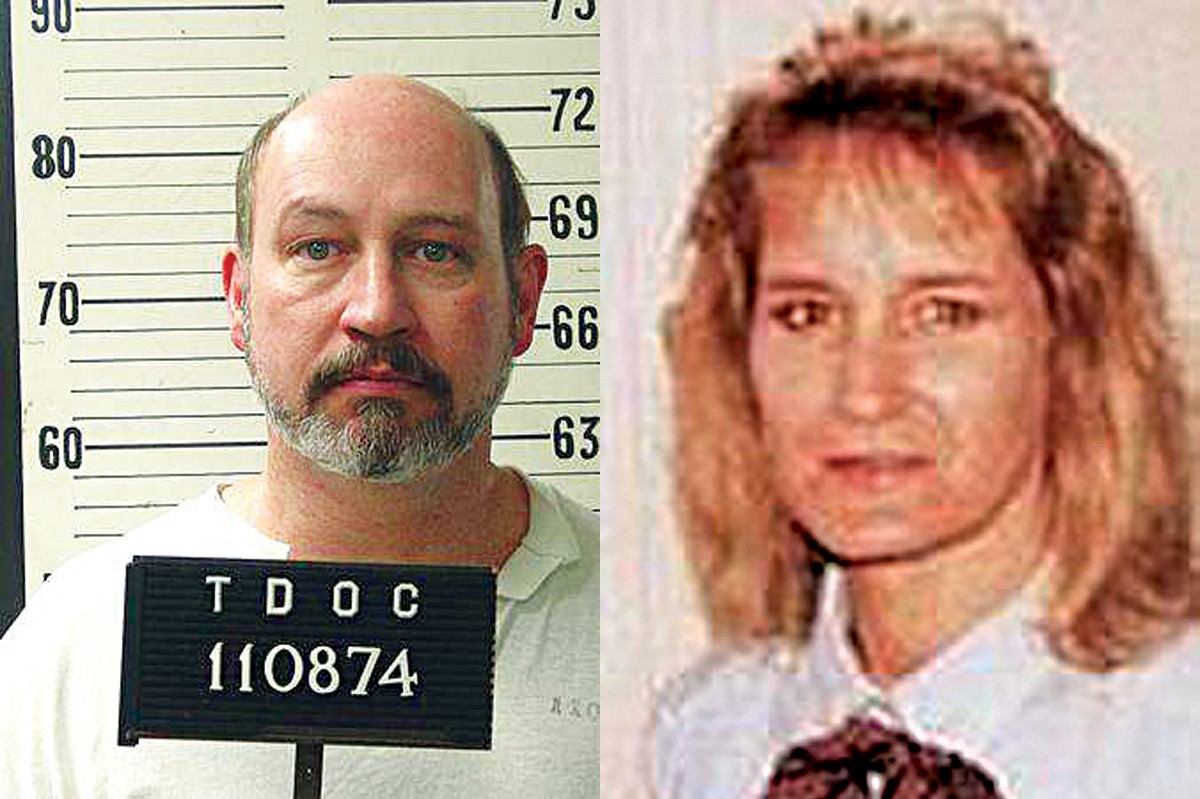

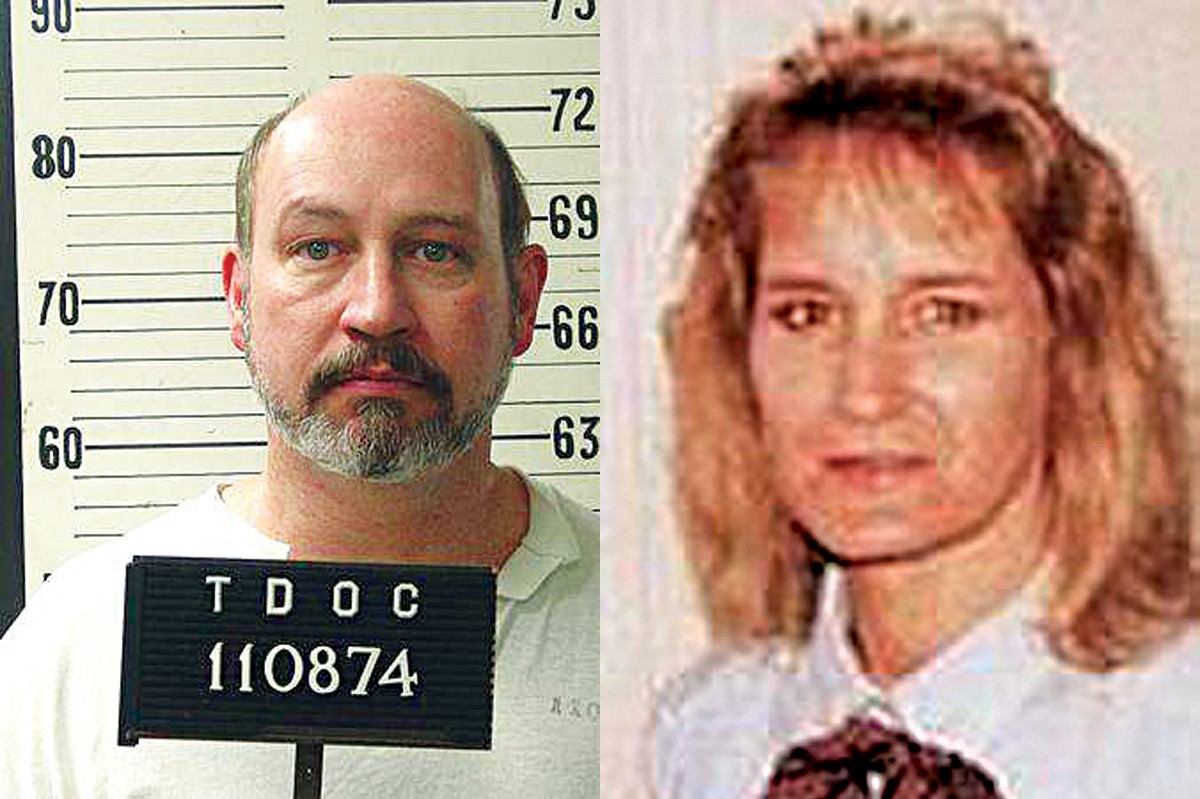

Accused murderer Michael Dale Rimmer and his alleged victim Ricci Ellsworth

It was not an ordinary crime. It was a murder case in which the victim’s body has never been found. That’s one reason Henderson decided to take it on, according to a letter he wrote in his defense to the Board of Professional Responsibility.

“Since I was the only one in the office who had ever tried such a case before, I agreed to take it on in addition to my regular caseload,” Henderson wrote.

A manager with CSX Transportation called the Memphis Inn early on February 8, 1997, to wake a work crew that was staying there. He was unable to get anyone on the phone at the front desk, so a railroad yardmaster then drove to the motel, located near the corner of I-40 and Sycamore View. When he got there, he found the office empty and signs of a violent struggle, including a blood trail leading out of the office door. The yardmaster called police.

Officers from the Shelby County Sheriff’s Department and the Memphis Police Department found large amounts of blood in the employee bathroom, a cracked sink, bloody towels, and the seat had been torn off the toilet. Sheets were taken, as well as $600 from the register. Ricci Ellsworth, the motel night clerk, was gone. Her 1989 Dodge Dynasty was still in the parking lot. Her body has not been found. She disappeared, but not without a trace.

An eyewitness, James Darnell, told police he saw two white men with blood on their hands in the motel around the time Ellsworth went missing. Darnell thought one of them was a motel clerk because he was behind the office window and was handing what he thought was change to the other man. Their knuckles were bloody, he said, and he thought they had been fighting.

He saw one of the men in the parking lot putting something “rolled up” in a motel comforter in the trunk of a car, something heavy enough that the car “dropped a little bit.”

Darnell described the men to a police sketch artist and the photos ran on television and in The Commercial Appeal. Billy Wayne Voyles and Raymond Cecil were identified by one of their friends in Arkansas. Police added a photo of Voyles (but not Cecil) to a photo spread and he was identified by the eyewitness, Darnell.

Voyles was brought to Tennessee on Henderson’s order, and he told police he hadn’t been in Tennessee for two years because he was running from a violation of parole warrant. He told police eight people (including Cecil) could verify his alibi.

Henderson said he was told Voyles had a good alibi and was excluded from his investigation. But Kelly Gleason, a post-conviction attorney who reviewed the case, concluded that none of the eight people were ever interviewed and that no D.A. or police document showed that his alibi checked out. Henderson said he chalked up Voyles as one of the “hundreds of false leads, crime-stopper tips, and false sightings of the victim that were checked out by police.”

But jurors in the 1998 trial never heard the name of Billy Wayne Voyles. They never knew an eyewitness claimed to have seen other suspects at the Memphis Inn that night.

Instead, they heard a story about a man named Michael Dale Rimmer. The eyewitness, Darnell, did not pick Rimmer out of the photo spread shown to him by police. Rimmer became the prime suspect for police and prosecutors, but their suspicions of him did not come out of thin air.

Rimmer had a sporadic romantic relationship with Ricci Ellsworth and was convicted of raping her in 1989. For that, he spent eight years at Tiptonville’s Northwest Correctional Facility (now called Northwest Correctional Complex). He got out just a few months before Ellsworth went missing. And on that day, February 8, 1997, Rimmer showed up early at his brother’s house, filthy with mud on his boots and asking his brother, a carpet cleaner, if he knew how to get blood out of carpet. He cleaned his muddy boots in the shower and was asked to leave.

He left Tennessee driving a stolen car. Receipts show he wound his way through Mississippi and Florida, then out west to California, Arizona, and Texas. About a month after he left Memphis, he was pulled over in Johnson County, Indiana. The cops ran the tag, which matched a stolen, maroon, 1988 Honda Accord that belonged to one of Rimmer’s acquaintances. Its driver was wanted for questioning in Tennessee.

Rimmer was locked up, and Indiana law enforcement officials ran tests on what looked like blood in the backseat of the car. Initial DNA results showed the blood “was consistent with the offspring of the victim’s mother,” according to court documents. More testing proved the blood belonged to Ricci Ellsworth, the only trace left of the missing woman, and all that police would ever find.

While in the Indiana jail, Rimmer told inmates he had killed his wife in a Memphis motel. He said she was responsible for his prior incarceration on the rape charge and that she owed him money. He described the murder scene as “very bloody,” described the place he dumped the body, and said he was surprised no one had found it yet. Back in Memphis, he told police he’d been to a topless club that night. An officer told him that Ellsworth might be dead and he said “you can’t have a murder, because you don’t have a body.” No one had told Rimmer that police had not found her body. It was damning evidence for sure.

Before the November 1998 trial, Rimmer’s team of six attorneys asked Henderson and the Shelby County prosecutors if there was any exculpatory evidence, or evidence that could help prove their client’s innocence. They specifically requested information “relating to any witness’ description of a perpetrator which did not match that of Mr. Rimmer,” according to the Board of Responsibility’s petition of discipline for Henderson. Henderson did not mention Billy Wayne Voyles. He said he was “unaware” of any such evidence.

Henderson said he did not suppress any evidence. In his defense letter to the board, he said he gave defense attorneys the names and addresses of all the questioned witnesses and told them the photo spread (which contained Rimmer and Voyles) and all reports of identification were available to them in the evidence room at 201 Poplar.

“It makes no sense that someone would try to hide such information and then furnish defense attorneys with names, addresses, descriptions, and notations of photo spreads,” Henderson wrote in the 2012 letter. “It was also my expectation that any defense attorney would examine the evidence in preparation for a trial. Sadly, that was not the case here.”

The Rimmer case file contained about 6,000 pages, Henderson said. So, when he was asked about any other eyewitness identification, he simply couldn’t recall Darnell’s identification of Voyles, especially since he wasn’t a person of interest in his investigation. “In short, my failure was one of recollection and not purposeful.”

But Kelly Gleason, a Nashville attorney who worked for Rimmer, disagreed that Henderson simply forgot. She pointed to the fact that Henderson specifically asked for Darnell in his lineup of potential witnesses, according to a letter to the Board of Professional Responsibility answering Henderson’s defense.

Also, she said the witness list Henderson prepared for his personal use included the remarks “saw 2 mw ID Voyles” by James Darnell’s name, meaning Darnell said he saw two white men at the motel that night and identified one of them as Voyles. The witness list given to Rimmer’s attorneys “contained no such description,” Gleason wrote.

“Mr. Henderson did not forget that James Darnell identified Billy Wayne Voyles,” Gleason said in her letter. “He chose not to disclose that fact to defense counsel before, during, and after Mr. Rimmer’s November 1998 trial.”

If the defense had known of an eyewitness at the time and place of Ricci Ellsworth’s disappearance, they could have formed a whole new trial strategy working from a completely different theory, all ideas and arguments that could have spared Rimmer from death row. But they didn’t, and Rimmer was convicted and sentenced to death.

Rimmer won an appeal, and the Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the convictions against him but overturned his death sentence. But the case was not overturned because of anything done by Henderson. It was overturned because the judge on the case gave incorrect instructions to the jury. In 2004, Rimmer got a new trial for sentencing that could keep him from the death chamber.

Henderson argued the new trial for the state against Rimmer. He used the same 1998 file to prepare for the case, Gleason said, and had the same witness list with his notes. Rimmer’s attorneys asked if Henderson had any exculpatory evidence regarding identification of witnesses. He said that “the identification witnesses in this case are friends, co-workers, and other acquaintances of the defendant,” according to the board’s discipline petition, which also noted that “Mr. Darnell was not a friend, co-worker, or other acquaintance with Mr. Rimmer.” Henderson later testified that he did not call Darnell to the re-sentencing hearing because the state was just presenting an outline of the evidence presented at the guilt phase of the initial trial.

“When the issue of Darnell’s review of a photo spread came up during the trial, Mr. Henderson stated that he reviewed the entire file and that James Darnell did not identify anyone in the photo spread,” Gleason wrote.

Henderson said in his defense that the allegation that he committed perjury “is perhaps the most offensive.” He testified at the post-conviction hearing that “I would not do such a thing” and that the court found that he had not “proven that false testimony had been purposely presented.” He said it was an “unsupported allegation” and pointed to the fact that “I am still practicing and have 40 years of honorable service. All of those years of service are to be held for naught because of an allegation of an adversary?”

Weirich backed up Henderson’s 2012 claim last week, pointing to the fact that Rimmer’s attorneys brought up James Darnell in their arguments without being explicitly told about him as a witness by Henderson.

The jury in the 2004 trial gave Rimmer the death sentence, primarily based on the evidence that he had a previous felony for raping Ellsworth. The appeals court and the Supreme Court affirmed the sentence.

In 2008, Rimmer filed motions for new lawyers to look at his case and to stay his execution. In 2009, he filed to have the Shelby County D.A.’s office disqualified from any new trial. It was denied twice. The Supreme Court held a hearing to see if the D.A.’s office should be disqualified from the case and said it shouldn’t be. Rimmer appealed the decision and was denied. But he won a chance for new hearings for new evidence in his case, which were heard in January and March 2012. Those hearings revealed that Rimmer’s attorneys in 2004 failed to bring forward the evidence about Darnell’s eyewitness identifications and failed to interview him before the trial. So, the resentencing jury never heard that he had seen two people at the Memphis Inn that night and that neither one was Michael Dale Rimmer.

For this, Judge James Beasley of the Division 10 of the Shelby County Criminal Court, found their counsel to be “ineffective,” and without that evidence, the 2004’s jury was “not reliable.” So, in his October 2012 court order, Beasley reversed Rimmer’s conviction and death sentence and said he was entitled to a new trial.

Weirich said again last week that the new case was granted not because of anything Henderson did but because Rimmer’s attorneys failed to use evidence that some say Henderson suppressed. “Mr. Henderson made a human error,” she said. “That’s it. End of story. Period.”

But Beasley found the exact opposite to be true. He wrote in his order that Henderson “purposefully misled counsel with regard to the evidence obtained in this case.” He said Henderson’s assertions in the 1998 and 2004 cases that “he knew of no evidence exonerating or exculpating (Rimmer) were blatantly false, inappropriate, and ethically questionable,” but it was not enough to reverse Rimmer’s conviction or sentence.

Rimmer’s new trial is scheduled for July. But that date is fluid now, after Weirich announced recently that she decided to recuse her office from the trial. She had pulled Henderson from the trial last year and put two other prosecutors on the case, but she said media coverage of Henderson’s censure had complicated the matter and further involvement by her office would be a “distraction.”

A judge and a new jury will again hear all of the details of the Rimmer case. But one thing will be different this time around. Thomas Henderson won’t argue for the state. Weirich requested and got a special prosecutor to handle the case. That means new prosecutors will need to learn all the facts of the Rimmer case and try to keep him behind bars — or worse. The speed of their learning curve will likely determine the trial date.

Rimmer maintains his innocence in the disappearance and apparent murder of Ricci Ellsworth even after two juries have agreed that he is to blame.

Henderson claimed his innocence in his defense letter last year, denying that he purposefully withheld evidence as he tried to prove Rimmer’s guilt. He maintains that innocence, even after a criminal court judge ruled his infractions were intentional, he was charged by the Board of Professional Responsibility, and he pled guilty to the charges.

Henderson will continue to work at the D.A.’s office, as he has since 1976. Weirich faces an election this year, and she was unyielding when asked what she would say to an opponent who brings up her decisions on Henderson.

“I’m going to say I made the right decision from the very beginning of even becoming the District Attorney General,” she said.

Maybe her confidence comes from details of the case that neither she nor anyone in her office can discuss. The case is now pending (for the third time) and Weirich said she’s having to defend Henderson and her decisions with “one hand and one leg tied behind my back.”

“I don’t condone these actions, but there’s also more to this than the public knows right now,” Weirich said. “When the case is over, we’ll be able to talk a lot more freely about it.”