Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

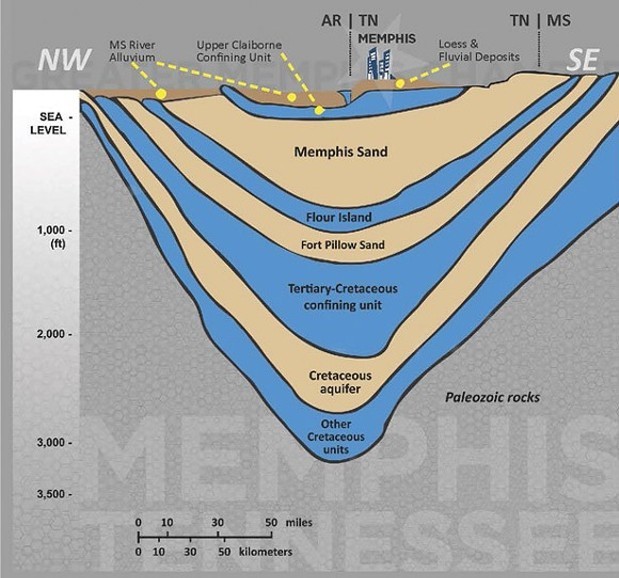

A diagram shows the layer of aquifers underneath Memphis.

Carrier Corp.’s plan to inject 400 gallons of treated wastewater into the Memphis Sand Aquifer every minute was paused Monday by the Shelby County Groundwater Quality Control (SCGQC) board.

The air-conditioning and refrigeration system manufacturer’s Collierville plant is a federal Superfund site with high levels of trichloroethylene (TCE) and hexavalent chromium. Both contaminants have been found in shallow parts of the aquifer under the plant.

Its current water-treatment process could be more efficient, a consultant to the company said. But the new plan would inject its treated wastewater deep into the aquifer, the source of Memphis’ famously pure drinking water. Experts familiar with the plan at the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) said the plan could put the “Memphis Sand Aquifer at risk of greater contamination.”

SCGQC board chairman Tim Herndon said “what bothers me is that you’re saying, ‘oh yeah, just let us get started and let us dump all this stuff into our aquifer.’” Many on the board had similar questions. Carrier’s request was paused to a later meeting in March.

Benjamin Brantley, working on the project for Carrier with environmental consultants Ensafe, said the company is not “recklessly dumping stuff into the aquifer.” Instead, he said the whole plan was created and vetted with Ensafe by officials with the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

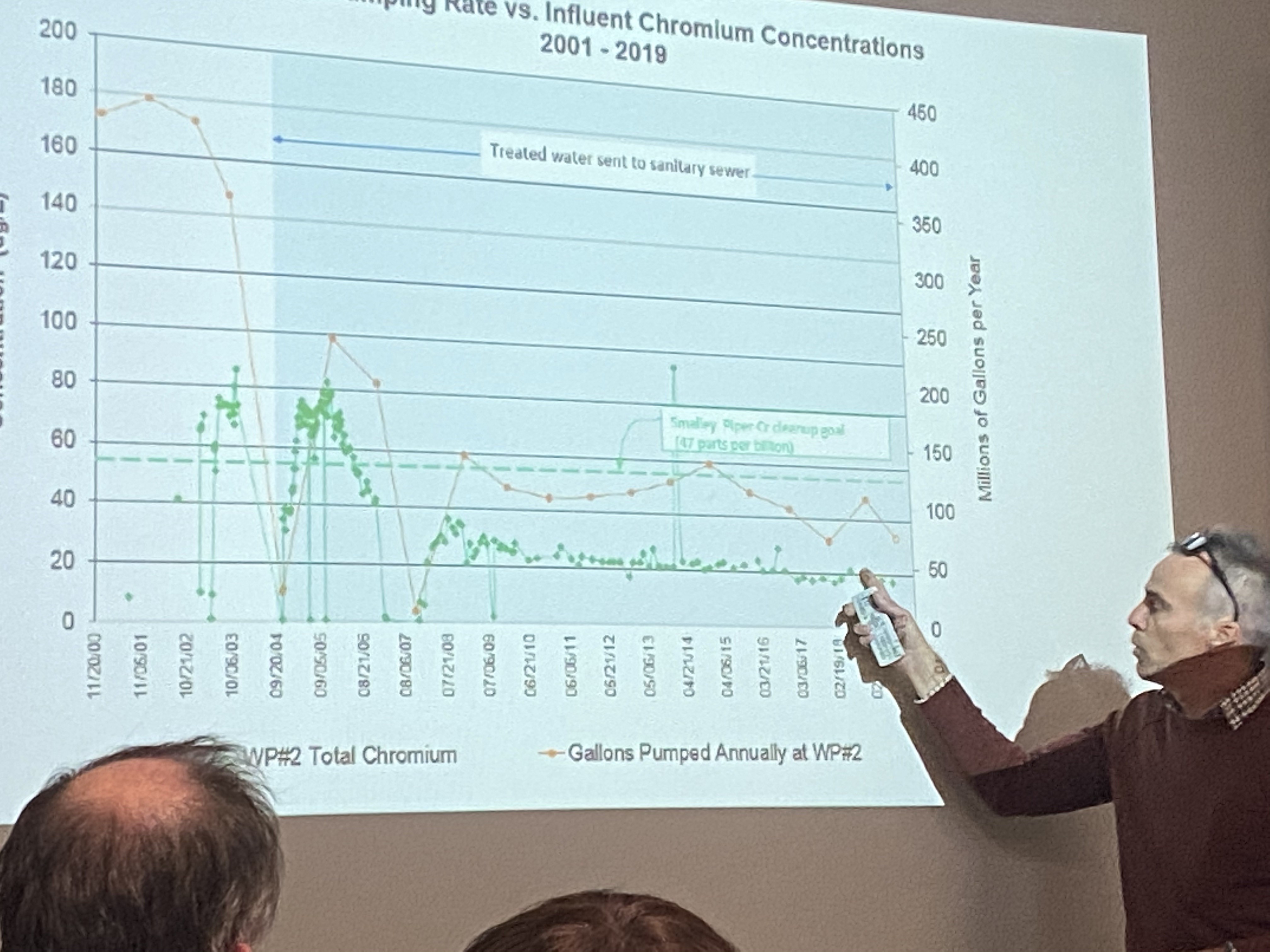

However, Herndon said he was skittish about those agencies as they installed an injection well on the Smalley-Piper site, without the groundwater board’s approval.

Carrier now cleans its water with onsite strippers and moves it to a Collierville-owned water treatment facility, adjacent to the Carrier site. That water is mingled with the rest of Collierville’s waste water and flowed into the Wolf River.

Carrier wants to move two wells farther south on its property off Byhalia Road. It would move the wells away from the nearby Smalley-Piper Superfund site, another contaminated site with high levels of chromium. The new wells would also pull water from the top of the aquifer where much of the contamination sits under the Carrier plant.

The plan would also allow its pumps to run all the time, cleaning more water. The water would filter through two towers where the contaminants would be stripped of contaminants, according Brantley. Then, the water would be pumped over to that water treatment facility owned by the city of Collierville. From there, it would be pumped into existing wells under the facility deep into the Memphis Sand Aquifer, instead of flowing it into the Wolf River.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Benjamin Brantley, working on the project for Carrier with environmental consultants Ensafe, presents his plan Tuesday.

Brantley said the water that would be pumped into the aquifer would be cleaned to “drinking-water standards.” However, Brantley admitted telling people they are drinking water from a Superfund site is a “tough sell.” He said, too, that pumping 200 million gallons of clean water back into the deeper parts of the aquifer would help to clean the aquifer.

The plan was denied by the Shelby County Health Department in October. It was then appealed to the groundwater board.

The SELC asked the groundwater board here to deny the appeal, in a letter written on behalf of Protect Our Aquifer and the Tennessee Chapter of the Sierra Club. In it, the group said Carrier’s plan is illegal as “injection wells are expressly prohibited by Shelby County and the Well Code does not authorize any variances allowing injection wells.”

“Carrier Corporation’s proposal provides a good example of why Shelby County is right to prohibit injection wells without any exceptions,” reads the letter. “These injection wells would be installed in the midst of Carrier Corporation’s own TCE contaminated groundwater plume and the chromium plume, threatening to mobilize those contaminants even deeper into the Memphis Sand Aquifer, which serves as the drinking water source for Collierville and Shelby County.”

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

A protest sign from Kathleen Meier reads: ‘Carrier Corp. work on a better solution. Don’t poison Memphis.’

The SELC said Carrier’s Superfund site has extremely high levels of trichloroethylene (TCE) contamination. According to the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), exposure to TCE can affect the central nervous system with symptoms like dizziness, headaches, confusion, euphoria, facial numbness, and weakness. Studies report TCE exposure to be associated with several types of cancers in humans, especially kidney, liver, cervix, and in the lymphatic system, according to the EPA.

But the SELC said that Carrier also detected hexavalent chromium in the well it has proposed to use for injection. This state of the element chromium is “known to cause cancer. In addition, it targets the respiratory system, kidneys, liver, skin, and eyes,” according to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The SELC experts said Carrier’s hexavalent chromium was likely originally drawn from the adjacent Smalley-Piper Superfund site, for which EPA is responsible.